Prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA helicases: Essential molecular motor proteins for cellular machinery (original) (raw)

Abstract

DNA helicases are ubiquitous molecular motor proteins which harness the chemical free energy of ATP hydrolysis to catalyze the unwinding of energetically stable duplex DNA, and thus play important roles in nearly all aspects of nucleic acid metabolism, including replication, repair, recombination, and transcription. They break the hydrogen bonds between the duplex helix and move unidirectionally along the bound strand. All helicases are also translocases and DNA‐dependent ATPases. Most contain conserved helicase motifs that act as an engine to power DNA unwinding. All DNA helicases share some common properties, including nucleic acid binding, NTP binding and hydrolysis, and unwinding of duplex DNA in the 3′ to 5′ or 5′ to 3′ direction. The minichromosome maintenance (Mcm) protein complex (Mcm4/6/7) provides a DNA‐unwinding function at the origin of replication in all eukaryotes and may act as a licensing factor for DNA replication. The RecQ family of helicases is highly conserved from bacteria to humans and is required for the maintenance of genome integrity. They have also been implicated in a variety of human genetic disorders. Since the discovery of the first DNA helicase in Escherichia coli in 1976, and the first eukaryotic one in the lily in 1978, a large number of these enzymes have been isolated from both prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems, and the number is still growing. In this review we cover the historical background of DNA helicases, helicase assays, biochemical properties, prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA helicases including Mcm proteins and the RecQ family of helicases. The properties of most of the known DNA helicases from prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems, including viruses and bacteriophages, are summarized in tables.

Keywords: DNA helicase, helicase assay, recombination, repair, replication

Abbreviations

Cdc

cell division cycle

CDK

cyclin‐dependent kinase

DDK

Cdc7–dumb bell former 4 (Cdc7–Dbf4)

Mcm

minichromosome maintenance

PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

PDH

pea DNA helicase

RPA

replication protein A

SV40

simian virus 40

Genetic information is locked in the duplex DNA of the genome. To access this information for many important biological processes, the duplex DNA has to be transiently unwound. For this purpose, a diverse class of enzymes has evolved, known as ‘DNA helicases’. They catalyze the unwinding of duplex DNA and thus play an essential role in many cellular processes, including DNA replication, repair, recombination, and transcription [1, 2, 3]. They are also thought to be motor proteins translocating along DNA using nucleoside triphosphate hydrolysis as the source of energy [4]. Multiple DNA helicases have been isolated from different organisms [1, 2, 3, 5]. Most contain short conserved amino‐acid fingerprints called helicase motifs. They are named Q, Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, V and VI. The helicases of this family are also called DEAD/H helicases [6, 7, 8]. This review focuses on the general aspects of DNA helicases including historical background, biochemical assays and biochemical properties. In addition, we have also covered the minichromosome maintenance (Mcm) proteins and RecQ family of helicases and summarized the characteristics of most of the known DNA helicases from prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems.

Historical perspective

DNA helicase was first discovered in E. coli in 1976 and classified as a ‘DNA unwinding enzyme’[9]. In 1978 the existence of the first eukaryotic DNA helicase was reported in the lily [10]. Since then, several different DNA helicases have been isolated from many organisms from both prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems. Recently, a new helicase motif, named the ‘Q motif’, has been identified in the DEAD‐box family of helicases [8]. The major milestones in the discovery of DNA helicases are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Historical background of DNA helicases.

| Year | Discovery |

|---|---|

| 1953–76 | Prehelicase years |

| 1953 | Duplex structure of DNA was solved [55] |

| 1967 | Rep protein was the first helicase in E. coli to be identified by genetic criteria [56] |

| 1976 | Hoffman‐Berling isolated first DNA helicase (helicase I, a traI gene product) from _E. coli_[9] |

| 1978 | Existence of the first eukaryotic DNA helicase was reported from the lily [10] |

| 1979 | E. coli Rep protein was shown to contain DNA helicase activity [57] |

| 1982 | First bacteriophage protein reported as DNA helicase was T4 gene 41protein [11] |

| 1982–83 | A direct biochemical assay (strand displacement assay) for measuring helicase activity was developed [11, 12] |

| 1985 | First mammalian DNA helicase was reported from calf thymus [58] |

| 1986 | First viral encoded protein reported as DNA helicase was SV40 large tumor antigen [59] |

| First yeast protein reported as DNA helicase was ATPase III [60] | |

| 1988 | Hodgeman and Gorbalenya discovered helicase motifs (seven conserved amino acid domains) [9, 61] |

| 1989 | Two helicase superfamilies (SF1 and SF2) were reported [62] |

| DEAD box helicase family was identified [7] | |

| 1990 | First human DNA helicase (HDH) reported in the purified form [63] |

| E. coli RecQ protein was reported as DNA helicase [43] | |

| 1992 | First mitochondrial DNA helicase was isolated from bovine brain [64] |

| 1996 | First chloroplast DNA helicase was reported in the purified form from the pea [65] |

| Crystallization of First DNA helicase (PcrA from thermophilic bacterium) was reported [66] | |

| 1997 | Mcm4/6/7 protein complex from HeLa cells was reported as a DNA helicase [37] |

| Werner syndrome protein (WRN) was reported as a DNA helicase [67] | |

| Bloom's syndrome (BLM) gene product was reported as a DNA helicase [68] | |

| 1998 | Sgs1 (slow growth suppressor), a RecQ helicase from yeast, was reported as a DNA helicase [69] |

| 2000 | First plant DNA helicase gene (PDH45) encoding the biochemically active enzyme was cloned [30] |

| First eIF‐4A (from pea) was reported as a DNA helicase [30] | |

| 2002 | First biochemically active malarial parasite DNA helicase was reported [34] |

| 2003 | A new helicase motif (Q motif) was identified in DEAD box helicases [8] |

| Presence of Helitron insertion, a DNA helicase bearing transposable element, reported from maize genome [70] |

Biochemical assay

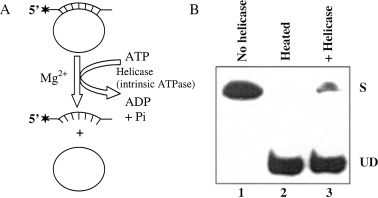

The most widely accepted and direct assay for measuring helicase activity in vitro was developed almost simultaneously by the Nossal and Richardson groups [11, 12]. Helicase partially unwinds duplex DNA substrate (32P‐labeled oligonucleotide annealed to a longer ssDNA molecule) yielding two ssDNA molecules of different sizes which are resolved from the starting duplex by electrophoresis followed by autoradiography (Fig. 1). The radioactive label in the DNA permits direct visualization (Fig. 1B) and quantitation of the results. Several other assays have also been developed but are not commonly used: for example, a rapid quench‐flow method [13], fluorescence‐based assays [14], filtration assay [15], a scintillation proximity assay [16], a time resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay [17], an assay based on flashplate technology [18], homogeneous time‐resolved fluorescence quenching assay and electrochemiluminescence‐based helicase assay [19]. Xu et al. [20] recently developed a new method for simultaneous monitoring of DNA binding and helicase‐catalyzed DNA unwinding by fluorescence polarization.

Figure 1.

Scheme of biochemical assay for measuring unwinding activity of ATP/Mg2+‐dependent DNA helicase (A) and autoradiogram of the gel (B). (A) Asterisks denote the 32P‐labeled end of the DNA. The partial duplex DNA helicase substrate was prepared by annealing the radiolabeled DNA oligo to M13 ssDNA (circular) as described previously [65]. (B) Lane 1, reaction without enzyme; lane 2, heat‐denatured substrate; lane 3, reaction in presence of DNA helicase enzyme. S, Substrate; UD, unwound DNA.

Biochemical properties

The basic unwinding reaction catalysed by all of the known DNA helicases is similar. They all share the following common biochemical properties: nucleic acid binding; NTP binding; nucleic acid‐stimulated hydrolysis of NTP; NTP/dNTP hydrolysis‐dependent unwinding of duplex nucleic acids with specific polarity.

Binding to nucleic acid

Helicases usually need ssDNA as a loading zone where they bind in a sequence‐independent manner and translocate unidirectionally. In general, they bind to ssDNA with higher affinity than to dsDNA. However, RecBCD, simian virus 40 (SV40) large antigen, and RuvB helicases preferentially bind to dsDNA. Many helicases need a replication fork‐like structure on the substrate for optimum unwinding. Some DNA helicases such as RecBCD, UvrD, Rep and RecQ from E. coli and SV40 large T antigen can also initiate unwinding from the ends of blunt‐ended duplex DNA [2]. RecG, RuvA and RuvB helicases of E. coli specifically recognize Holliday junctions [21, 22]. Usually oligomeric helicases carry multiple ssDNA‐binding sites, although all the sites may not simultaneously bind to the DNA. For example, E. coli DnaB [23] and bacteriophage T7gp4 [24] DNA helicases contain six DNA‐binding sites even though only one or two subunits interact with ssDNA at a time.

NTP binding and nucleic acid‐stimulated hydrolysis of NTP

All DNA helicases bind NTP and exhibit nucleic acid‐dependent intrinsic NTPase activity necessary for duplex unwinding. In general, replicative hexameric helicases bind ssDNA tightly in the presence of NTP, and weakly in the presence of NDP. This binding results in a conformational change in homo‐oligomeric helicases and thereby affects the assembly state of the protein. NTP does not bind with equal affinity to all the sites in hexameric helicases. In general, the DNA helicases are poor NTPases in the absence of ssDNA and their NTPase activities are stimulated by the presence of ssDNA.

Polarity of DNA unwinding

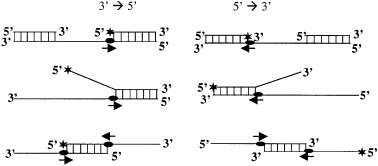

DNA helicases exhibit specific polarity, which is defined as the direction of DNA helicase movement on initially bound ssDNA template (i.e. 3′ to 5′ or 5′ to 3′) with respect to the polarity of the sugar phosphate backbone. The polarity of unwinding by DNA helicase can usually be determined by using a DNA substrate consisting of a linear ssDNA template with duplex regions near the end(s). Possible structures of substrates that can be used for directional study in vitro are shown in Fig. 2. For helicases involved in DNA replication, the polarity of the reaction is strongly indicative of helicase placement on the leading (3′ to 5′ polarity) or lagging (5′ to 3′ polarity) strands. It has been reported that RecBCD contains bipolar enzyme activitiy, where RecB and RecD components of the complex unwind DNA from 3′ to 5′ and 5′ to 3′ directions, respectively [25]. Interestingly, PcrA helicase from Bacillus anthracis showed robust 3′ to 5′ as well as 5′ to 3′ helicase activities, with substrates containing a duplex region and a 3′ or 5′ ss poly(dT) tail [26]. Recently, Constantinesco et al. [27] have shown that the HerA DNA helicases from thermophilic archaea is able to utilize either 3′ or 5′ ssDNA extensions for loading and subsequent DNA duplex unwinding.

Figure 2.

Structures of the linear partial duplex substrates commonly used to determine the direction of translocation of the helicase. The 3′ to 5′ directional substrates are on the left and 5′ to 3′ directional substrates are on the right. Asterisks denote the 32P‐labeled end.

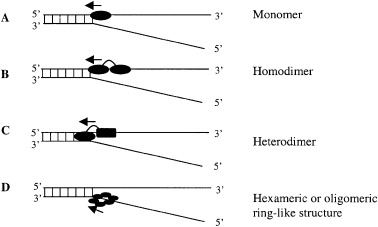

Monomeric and oligomeric nature of helicases

The fact that many helicases function as hexamers, as well as the necessity for multiple DNA‐binding sites, has led to the suggestion that oligomerization may be necessary for helicase function. The property of an oligomeric helicase is that it possesses multiple DNA‐binding sites, a feature that is required for any ‘active’ mechanism of DNA unwinding, because it enables a helicase to bind both ss and duplex DNA or two strands of ssDNA simultaneously at an unwinding fork. On the basis of active assembly of DNA helicases, they can be grouped as monomeric or multimeric helicases. Figure 3 shows the interaction of different forms of DNA helicases with a DNA‐unwinding fork. In all these models, at least one subunit always binds to the ssDNA track along which it moves [28]. The other subunit may bind to the dsDNA. On the other hand the monomeric helicases may contain two different domains, one for ssDNA and the other for dsDNA binding. The bacterial helicases II, IV and PriA ([1] and references cited therein), bacteriophage T4 Dda helicase [29], human DNA helicase IV, V and VI [5], and pea DNA helicase 45 (PDH45) and PDH65 [30, 31] are the few examples of monomeric forms. It has been shown that UvrD from E. coli is active as a monomer [32].

Figure 3.

Interaction of monomeric or oligomeric DNA helicases with the DNA forked substrate. (A) Monomeric helicase binds to both ssDNA and dsDNA. (B) In homodimeric helicases, one subunit always binds to the ssDNA track along which it moves. (C) Heterodimeric helicase contains two separate domains: one subunit binds/interacts with dsDNA and anchors the helicase to the DNA lattice and the other subunit interacts with ssDNA and translocates along it. (D) Hexameric or oligomeric helicases contain a ring‐like structure that enables the proteins to encircle the DNA and thus prevent local reannealing. In this case one or more subunits bind to ssDNA at the ss/dsDNA junction.

The functionally active forms of many DNA helicases are oligomeric: E. coli DnaB, RuvB, RecBCD and Rho proteins, phage T7 gene 4 helicase/primase, phage T4 gene 41 helicase, SV40 large T antigen. All can assemble to form ring‐like toroidal hexamers [1, 2, 22, 23, 25, 28]. Electron microscopy studies have confirmed that the ssDNA transverses in the center of the hexameric ring. These results show that the hexameric G40P DNA helicase encircles the 5′ tail, interacts with the duplex DNA at the ss/dsDNA junction, and excludes the 3′ tail of the forked DNA [33]. Oligomerization of many DNA helicases can be modulated by interactions with other ligands. For example, the E. coli Rep helicase is a monomer up to concentrations of 12 mm in the absence of DNA but forms a dimer on binding to DNA [1].

Prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA helicases

DNA helicases have been isolated from many sources and accordingly named as prokaryotic, eukaryotic, bacteriophage, and viral helicases. More than one helicase is present in each system because of a variety of different needs for the duplex DNA to unwind in different DNA metabolisms. For example, at least 14 different DNA helicases have been isolated from a simple single cell organism such as E. coli(Table 2), six from bacteriophages (Table 3), 12 from viruses (Table 4), 15 from yeast (Table 5), eight from plants (Table 6), 11 from calf thymus (Table 7), and as many as 25 from human cells (Table 8). The properties of these DNA helicases are summarized in their respective tables. The first malarial parasite helicase protein has recently been purified which contains ATP/Mg2+‐dependent DNA unwinding and ssDNA‐dependent ATPase activities [34] and prefers to unwind DNA containing replicative fork‐like structures [35].

Table 2.

E. coli DNA helicases.

| S. No. | Name of helicase | Mol. mass (kDa) | Gene | Polarity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | DnaB protein a | 52 | dnaB | 5′−3′ | Replicative helicase. Moves on lagging strand of replication fork. |

| 2. | PriA proein b | 81.7 | priA | 3′−5′ | Replicative helicase. Formerly called n′‐protein. Binds to ssDNA at primosome assembly sites. |

| 3. | Rep protein c | 72.8 | rep | 3′−5′ | Replicative helicase, unwinds the phage DNA in a highly processive and catalytic manner. |

| 4. | UvrAB | 103 | uvrA | 5′−3′ | Repair helicase. Involved in nucleotide excision repair. |

| complex d | 76 | uvrB | UvrB is helicase component | ||

| 5. | Helicase II (UvrD) e | 82 | uvrD | 3′−5′ | Repair helicase. Involved in nucleotide excision repair. |

| 6. | Helicase IV f | 78 | helD | 3′−5′ | Originally called as 75 kDa helicase. Helicase activity stimulated by SSB. |

| 7. | RecQ g | 80 | recQ | 3′−5′ | Recombination helicase. |

| 8. | RecBCD | 13.4 | recB | 3′−5′ | Catalyzes the first step in the recombinational repair of dsDNA breaks. |

| complex h | 129 | recC | Highly processive helicase with bipolar polarity. | ||

| (exo V) | 66 | recD | 5′−3′ | ||

| 9. | RuvAB i | 22 37 | ruvA ruvB | 5′−3′ | Recombination helicase. It is an ATP‐driven translocase (pump) that promotes branch migration. |

| 10. | Helicase I j | 192 | tral | 5′−3′ | First helicase identified. May be involved in site‐specific nicking reaction. |

| 11. | RecG k | 76 | recG | 3′−5′ | A junction‐specific DNA helicase that acts postsynap‐tically to drive branch migration of holliday junction. |

| 12. | Rho l | 46 | rho | 5′−3′ | RNA·DNA helicase, can also unwind RNA·RNA but not DNA·DNA. |

| 13. | Helicase III m | 20 | ? | 5′−3′ | Smallest prokaryotic helicase. SSB protein inhibits the ATPase activity of the protein. |

| 14. | DinG n | ? | DinG | 5′−3′ | DNA damage inducible helicase. It is a monomer in solution. |

Table 3.

Bacteriophage DNA helicases. nd, Not determined; PNA, peptide nucleic acid.

| S. No. | Name of helicase | Mol. mass (kDa) | Nucleotide cofactor | Polarity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | T4 gene 41 a | 58 | dGTP > ATP = dATP > GTP | 5′−3′ | Essential for both the priming and helicase activities. Stimulated by T4 gene 59 protein and forked 3′ tail substrate. |

| 2. | T4 dda b | 56 | ATP, dATP | 5′−3′ | Can also unwind DNA‐PNA substrate. Inhibited by T4 gene 32 protein involved in the DNA replication. Oligomerization of dda is not required for DNA unwinding. |

| 3. | T4 UvsW c | 65 | ATP | Nd | Catalyzes branch migration and is involved in recombination, repair and the regulation of DNA replication origin. |

| 4. | T7 gene 4 d | 56 and 63 | ATP, dATP dGTP,dTTP | 5′−3′ | 56 kDa protein contains DNA helicase activity, while 63 kDa (with 63 amino acids more) contains both the helicase and primase activities. |

| 5. | P4 gene α e | 84.9 | ATP, dATP GTP, dGTP CTP, dCTP | 3′−5′ | Stimulated by forked substrate, contains pri‐mase and sequence specific (5′‐TGTTCAC C −3′) binding activity of ori and crr DNA. |

| 6. | G40P f | 300 | ATP, GTP, CTP, UTP | 5′−3′ | Essential for B. subtilis bacteriophage SPP1 replication. |

Table 4.

Viral DNA helicases. AAV, Adeno‐associated virus; ACNP, Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis; BPV, bovine papilloma virus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; MVM NS1, minute virus of mice–nonstructural protein; nd, not determined; OBP, origin binding protein; SV40 T‐antigen, Simian virus 40 large T antigen; SARS‐CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (Coronoviridae helicase).

| S. No. | Name of helicase | Mol. mass (kDa) | Nucleotide cofactors | Polarity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SV40 T‐antigen a | 94 | ATP > dATP > dTTP = UTP | 3′−5′ | Interacts with DNA pol. α; essential for DNA replication; contains both DNA and RNA helicase activities. |

| 2. | Polyoma T‐antigen b | 100 | ATP = dATP > CTP = UTP | 3′−5′ | Contains Polyoma ori binding and unwinding activities. |

| 3. | HSV‐1. UL5/UL8/UL52 Complex c | 120 97 70 | ATP > GTP > CTP = UTP | 5′−3′ | UL5 and UL52 required for helicase‐primase activity. |

| 4. | HSV‐1, UL9 protein d | 68 | ATP = dATP > CTP > dCTP | 3′−5′ | OBP involved during the initiation of HSV replication. |

| 5. | BPV‐1, E1 protein e | 68 | ATP, dATP, CTP, dCTP, UTP, dTTP, GTP, dGTP | 3′−5′ | OBP, which is stimulated by E2 protein of BPV‐1. |

| 6. | AAV, Rep68, Rep78 f | 68 71 | ATP > CTP > dATP > GTP > UTP | 3′−5′ | Contains site‐and strand‐specific endonuclease activity. |

| 7. | AAV‐Rep52 g | 52 | ATP, dATP, CTP, dCTP, UTP, dTTP, GTP, dGTP | 3′−5′ | Lysine to histidine substitution within motif I was deficient for both DNA helicase and ATPase activities. |

| 8. | AAV‐Rep40 h | 40 | ATP | 3′−5′ | Lysine to histidine mutation in the purine nucleotide‐binding site results in a protein that inhibits helicase activity. |

| 9. | MVM NS‐1 i | 83 | ATP > dATP | nd | Appears to have site‐specific endonuclease activity. |

| 10. | ACNP virus P143 j | 143 | ATP | nd | Stimulated by LEF3/SSB; essential for virus DNA replication. |

| 11. | Vaccinia virus A18R k | 57.5 | ATP | 3′−5′ | It is a DExH box protein and is involved in transcription. |

| 12 | SARS‐CoV helicase l | 70 | ATP, dATP, CTP > all others | 5′−3′ | Attractive target for anti‐SARS therapy. |

Table 5.

Yeast DNA helicases. nd, Not determined.

| S. No. | Name of helicase | Source | Mol. mass (kDa) | Nucleotide cofactors | Polarity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | ATPase III a | S. cerevisiae | 63 | ATP > dATP | 3′−5′ | Stimulated by yeast Pol I. |

| 2. | Rad3 b (XPD) | S. cerevisiae | 89 | ATP > dATP ≫ CTP | 5′−3′ | Active at acidic pH; involved in DNA excision repair; homologous to XPD gene. |

| 3. | Rad25 c (SSl2) | S. cerevisiae | 95 | ATP, dATP | 3′−5′ | Functions in nucleotide excision repair; homo logous to XPB; required for Pol II transcription. |

| 4. | Srs2d | S. cerevisiae | 134 | ATP, dATP | 3′−5′ | Involved in error‐prone repair; negatively modulates recombination. |

| 5. | PIF1 e | S. cerevisiae | 97 | ATP, dATP | 5′−3′ | Functions in mitochondrial DNA repair and recombination. |

| 6. | DNA helicase A f | S. cerevisiae | 90 | ATP, dATP | 5′−3′ | Copurifies with DNA Pol‐α‐ primase; helicase activity stimulated by the yeast RPA. |

| 7. | DNA helicase B g | S. cerevisiae | 127 | ATP, dATP > CTPdCTP, UTP | 5′−3′ | Copurifies with DNA Pol‐δ; stimulated by scRPA; encoded by the yORF61 gene |

| 8. | DNA helicase Ch | S. cerevisiae | 32 60 | ATP, dATP CTP,dCTP > UTP,GTP > dGTP | 5′−3′ | Copurifies with DNA Pol δ? |

| 9. | DNA helicase D i | S. cerevisiae | 60 | ATP,dATP > CTP,dCTP UTP | 5′−3′ | Copurifies with RF‐C. |

| 10. | ScHel I j | S. cerevisiae | 135 | ATP, dATP | 5′−3′ | Stimulated by E. coli SSB. |

| 11. | DNA helicase III k | S. cerevisiae | 120 | ATP, dATP | 5′−3′ | Encoded by a gene different from Rad3 and RadH. |

| 12. | Sgs1 l | S. cerevisiae | ATP, dATP | 3′−5′ | Binds more tightly to a forked DNA substrate than to ss and ds DNA. | |

| 13. | Dna2 m | S. pombe | 65 | ATP, dATP | 5′−3′ | Involved in DNA replication. |

| 14. | MER3 n | S. cerevisiae | 130 | ATP | 3′−5′ | Meiosis‐specific helicase: required for crossing over at time of first meiotic division. |

| 15. | Hmi1p helicase o | S. cerevisiae | 80 | ATP | nd | Mitochondrial helicase; required for the maintenance of mitochondrial genome. |

Table 6.

Biochemically active DNA helicases from plant cells. CDH, Chloroplast DNA helicase; DSBs, double‐strand breaks; HDH, human DNA helicase; nd, not determined; PDH, pea DNA helicase.

| S. No. | Name of helicase | Mol. mass (kDa) | Nucleotide cofactors | Polarity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Lily U‐protein a | 130 (native) | ATP | nd | Partially purified. Unwinds DNA from ends, gaps and nicks. Its abundance increases during meiosis. |

| 2. | Soybean chloroplast DNA helicase b | nd | ATP ≫ GTP > dATP > NTPs | nd | Partially purified. Shows unwinding activity at higher conc. of Mg2+ (10 mm). |

| 3. | Pea chloroplast DNA helicase I (CDH I) c | 68 138 (native) | ATP > dATP ≫ NTPs | 3′−5′ | First plant helicase reported in purified form. It is a homodimer. |

| 4. | Pea chloroplast DNA helicase II (CDH II) d | 78 | ATP = dATP | 3′−5′ | Purified to homogeneity. Stimulated by fork‐like structures. |

| 5. | Pea nuclear DNA helicase I (PDH45) e | 45 | ATP > dATP ≫ NTPs | 3′−5′ | First plant nuclear DNA helicase; homologous to eIF‐4 A; stimulates topo I activity. |

| 6. | Pea nuclear DNA helicase II (PDH65) f | 65 | ATP > dATP | 3′−5′ | A plant homolog of HDHI. localized in nucleo lus. Phosphorylated and upregulated by CK2 and cdc2 protein kinases. |

| 7. | Arabidopsis Ku DNA helicase (AtKu70/80) g | 70.3 76.7 | ATP | nd | Functions as heterodimer that binds to dsDNA. Gene expression is induced by DSBs, may be involved in DSB repair. |

| 8. | Pea nuclear DNA helicase III (PDH120) h | 54 66 120 (native) | ATP > NTPs | 3′−5′ | Purified to homogeneity. Present at extremely low abundance and contain the high specific activity. |

Table 7.

Calf thymus/bovine DNA helicases.

| S. No. | Name of helicase | Mol. mass (kDa) | Nucleotide cofactors | Polarity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | DNA helicase A a | 47 | ATP = dATP > CTP > dCTP | 3′−5′ | Copurifies with calf thymus DNA Pol‐α/?Primase; stimulated 20‐fold by RPA. |

| 2. | DNA helicase B b | 100 | dATP = ATP ≫ all other | 5′−3′ | Binds to dsDNA also. |

| 3. | DNA helicase C c | 40 | dATP = ATP ≫ all other | 5′−3′ | Stimulated by 100 mm KCl on short substrates. |

| 4. | DNA helicase D d | 100 45 | dATP = ATP | 5′−3′ | Stimulated 10‐fold by RPA and forms large aggregates in low salt. |

| 5. | DNA helicase E e | 104 | dATP = ATP | 3′−5′ | Copurifies with DNA Pol‐ε and dependent on unspecific SSB; probably involved in DNA repair. |

| 6. | DNA helicase F f | 72 | ATP, dATP, dCTP, UTP, CTP, GTP, dGTP, dTTP | 5′−3′ | Copurifies with RPA. In presence of RPA, this helicase can unwind longer duplexes |

| 7. | DNA helicase I g | 200 | ATP = dATP | 3′−5′ | Stimulated by 150 mm NaCl. |

| 8. | DNA helicase II h | 130 | ATP = dATP ≫ 1 other | 3′−5′ | Can unwind dsRNA also. |

| 9. | δ helicase i | 57 | ATP = dATP > CTP = UTP | 5′−3′ | Copurifies with DNA Pol. δ and acts as strand‐ displacement factor for Pol.δ |

| 10. | Cytosolic DNA helicase j | 110 | ATP = dATP > CTP, dCTP | 3′−5′ | All the three subunits bind to ATP. |

| 65 | |||||

| 34 | |||||

| 11. | Bovine mitochondrial helicase k | 57 | ATP = dATP | 3′−5′ | Possible role in mitochondrial DNA replication. |

Table 8.

Human DNA helicases. nd, Not determined.

| S. No. | Name of helicase | Mol. mass (kDa) | Nucleotide cofactors | Polarity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | HDH I a | 65 | ATP, dATP | 3′−5′ | Can also unwind DNA/RNA and RNA/RNA hybrids; may be involved in rDNA transcription. |

| 2. | HDH II/ | 87 | ATP, dATP | 3′−5′ | Functions in dsDNA break repair and V(D)J recombination; regulator of DNA‐dependent |

| Ku b | 72 | protein kinase | |||

| 3. | HDH III c | 46 | ATP, dATP | 3′−5′ | Prefers replication fork‐like structure of substrates |

| 4. | HDH IV d | 100 | ATP, dATP | 5′−3′ | Can unwind DNA/RNA hybrids |

| 5. | HDH V e | 92 | ATP, dATP | 3′−5′ | Has highest turnover rate |

| 6. | HDH VI f | 128 | ATP, dATP | 3′−5′ | Prefers replication fork‐like structure of substrates |

| 7. | HDH VII g | 36 | nd | nd | Trimer of one molecule of hnRNP A1 and two molecules of annexin II |

| 8. | HDH VIII h (G3GP) | 68 | ATP | 5′−3′ | A DNA and RNA helicase corresponding to G3 bp protein, an element of the RAS transduction pathway, similar to E. coli RecBCD |

| 9. | HDH IX g (RNP DO) | 45 | nd | nd | A Gly‐Arg rich protein identified as ribonuclear protein DO |

| 10. | XPD/ERCC2 i | 87 | ATP, dATP | 5′−3′ | Functions in nucleotide excision repair; component of BTF2‐TFIIH transcription factor. |

| 11. | XPB/ ERCC3 j | 89 | ATP | 3′−5′ | Functions in nucleotide excision repair; component of BTF2‐TFIIH transcription factor. |

| 12. | Helicase ε k | 72 | ATP, dATP, CTP | 3′−5′ | Helicase activity is dependent on HRP‐A |

| 13. | Helicase µ l | 110 | ATP, dATP, | 3′−5′ | Stimulated by 5′‐tailed fork and SSB. |

| 90 | CTP, dCTP | ||||

| 14. | RIP 100 m | 100 | ATP, dATP | 3′−5′ | Associated with RIP60; RIP60 binds to replication origin region of DHFR h |

| 15. | Helicase Q1 n | 73 | ATP, dATP | 3′−5′ | Gene homologous to E. coli RecQ gene; identical to human DNA helicase I |

| 16. | Helicase Q2 o | 100 | ATP | 5′−3′ | Identical with DNA helicase IV |

| 17. | HchlR1 p | 112 | ATP | 5′−3′ | Can unwind RNA/DNA substrates. Unlike others it can translocate along ssDNA in both directions when substrate have a very long ssDNA region. |

| 18. | HHcsA q | 116 | ATP, dATP | 5′−3′ | Hexameric protein. |

| 19. | WRN helicase r | 163 | ATP, dATP ≫ DCTP, CTP | 3′−5′ | Mutated in Werner syndrome, homologous to RecQ and contains 3′‐5′ exonuclease activity |

| 20. | BLM helicase s | ≈ 160 | ATP | 3′−5′ | Mutated in cells of Bloom's syndrome patient and belongs to RecQ family. |

| 21. | Mcm4/6/7 complex t | ≈ 600 | ATP, dATP | 3′−5′ | The DNA unwinding activity is stimulated by SSB and forked DNA structures; can function as a replication helicase. |

| 22. | HEL308 u | 124.5 | ATP, dATP | 3′−5′ | Homologous to DNA crosslink sensitivity protein Mus308 of D. melanogaster. Stimulated by RPA. |

| 23. | HFDH1 v | ≈ 120 | ATP | 3′−5′ | First F‐box protein that possesses enzyme activity. |

| 24. | Human RECQ1 w | 75 | ATP | 3′−5′ | Needs 3′ tail of 10 nt on the substrate to open the duplex; can unwinds blunt end substrate with bubble of 25 nt; stimulated by hRPA. |

| 25. | BACH1 x | 130 | ATP | 5′−3′ | A nuclear phosphoprotein interacts with tumor suppressor, BRCA1. Involved in DSB repair and contain tumor suppression activity. |

Mcm proteins

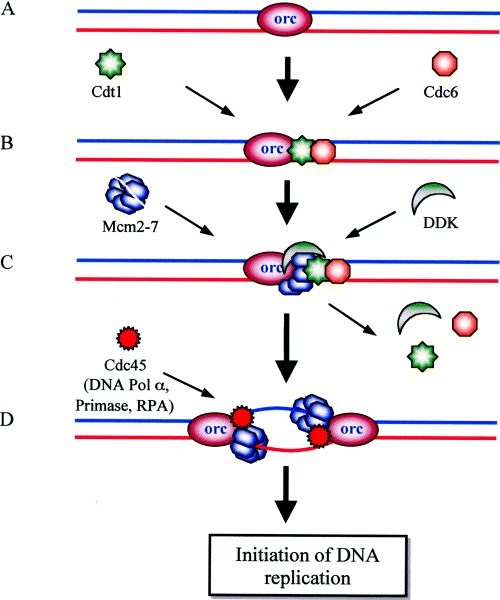

Mcm proteins (named because they were discovered as the products of genes essential for minichromosome maintenance in yeast) were identified initially for their role in plasmid replication or cell cycle progression. In eukaryotes, Mcm proteins 2–7 are required for initiation and elongation steps of chromosomal DNA replication [36]. The Mcm complex is now known to serve as a replicative helicase. A heterotrimeric complex of human Mcm4/6/7 forms a dimeric structure, contains ATP‐dependent DNA helicase activity, binds to ssDNA, and possesses DNA‐dependent ATPase activity [37], whereas Mcm2/3/7 serve as regulatory subunits. In the presence of forked DNA structures and single stranded DNA binding protein (SSBP), the Mcm4/6/7 complex possesses processive DNA helicase activity [38]. The six proteins (Mcm2–7) interact with each other to form multiple complexes; however, the predominant form is a hexamer containing all six Mcms, which is relatively stable. Electron microscopy indicates that this complex has a globular structure. In vivo studies suggest that all six Mcms are recruited to replication origins during the G1 phase [36]. During G1 phase human Mcm proteins first assemble at or adjacent to bound origin recognition complex along with cell division cycle (Cdc) 6 and Cdc10‐dependent transcript 1 (Cdt1) proteins (Fig. 4) and move to other sites during genome replication [39]. These proteins together form a prereplication complex at the origin of DNA replication at the beginning of the S phase. After assembly, the complex is activated by cyclin‐dependent kinases (CDKs) and the Cdc7–dumb bell former 4 (Cdc7–Dbf4, DDK) complex in the S phase to promote the initiation of DNA replication (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Recruitment to activation of Mcm complex during initiation of DNA replication at the origin. (A) The origin is ‘marked’ by the origin recognition complex (orc). (B) Assembly of the prereplication complex (pre‐RC) begins during the G1 phase, when the ‘loading factors’ Cdc6 and Cdt1 are recruited to the replication origin to which orc (and Mcm10) bind. (C) Two Mcm complexes (ring‐shaped hexamers) load on to the origin, which is facilitated by Cdc6 and Cdt1. The Cdc7‐Dbf4 kinase (DDK) is also recruited to the origin during the G1 phase and phosphorylates the Mcm complex during the S phase. (D) The loading factors have been displaced from the DNA; the phosphorylated two Mcm complexes (enzymatically active helicase) have moved apart along the template, generating a replication ‘bubble’ by unwinding and displacing the orc. At each ‘fork’ the Cdc45 protein binds. The loading of other DNA replication factors, such as DNA polymerase α, RPA, and primase, etc., start at the time of initial DNA melting, which leads to the initiation of DNA replication.

A growing list of proteins, including Mcm10 and Cdt1, are involved in the recruitment process. Actually the two protein kinases (CDK and DDK) trigger a chain reaction that results in the phosphorylation of the Mcm complex and finally in the initiation of DNA synthesis [36, 39, 40]. Recruitment of DDK to the replication origin occurs during the G1 phase. However, it must function sometimes during the S phase, and this decision is controlled locally at individual origins. Phosphorylation of Mcm2 by DDK results in a conformational change in the Mcm complex. Recruitment of Cdc45 depends on phosphorylation of the Mcm complex and the activity of CDK. The Mcm component of the complex provides the DNA‐unwinding function (Fig. 4) to start the DNA replication, which finally requires the concerted action of many enzymes/factors such as replication protein A (RPA), polymerase α, replication factor C, polymerase δ, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), flap endonuclease 1, endonuclease DNA2, and DNA ligase I [35, 39]. The unwinding of origin DNA is detected only at a later step when the Mcm complex is phosphorylated by DDK at the G1 to S phase transition [40]. These studies suggest an anchoring mechanism other than direct contact with DNA for the Mcm complex immediately after its recruitment to the replication origins. Recently it has been reported that the Mcm8 protein from HeLa cells, a new member of the Mcm family, forms a complex with Mcm4, Mcm6 and Mcm7 proteins and this complex is involved in initiation of DNA replication [41].

RecQ family of DNA helicases

RecQ is a recombination‐specific DNA helicase from the SF2 family. Members of the RecQ family of DNA helicases are involved in processes linked to DNA replication, DNA recombination, and gene silencing. It was discovered and named RecQ by H. Nakayama of Kyushu University, Japan (‘Q’ came from Kyushu) [42]. This gene was discovered during a search for genes that control the loss of viability in thymine‐starved bacteria, a classic phenomenon known as thymineless death. RecQ1 mutant was resistant to thymineless death, and, in a recBCsbcB background, it exhibited enhanced UV sensitivity and a deficiency in conjugational recombination, suggesting a role for RecQ in the RecF recombination pathway [42]. RecQ protein was purified to homogeneity and shown to be a helicase that unwinds duplex DNA in the 3′ to 5′ direction with respect to the single strand to which it binds [43].

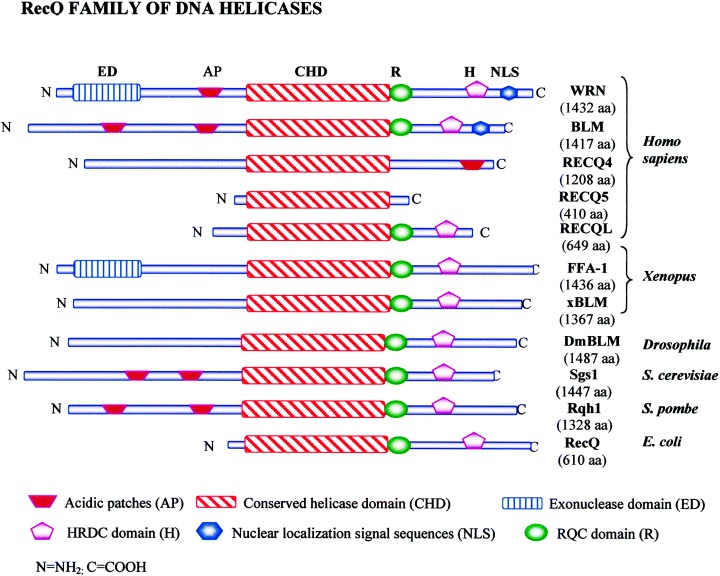

The family name ‘RecQ’ is derived from the E. coli RecQ helicase. In general, unicellular organisms express a single RecQ enzyme, whereas more complex organisms express two or more. All helicases of this family share a central seven helicase motifs. RecQ DNA helicases are proposed to function at the interface between DNA replication and recombination to ‘repair’ the damaged replication forks [44]. This family includes at least five members in humans, and the following three are defective in genetic disorders associated with cancer and/or premature aging: WRN, BLM and RECQ4 helicases defective in Werner's syndrome, Bloom's syndrome, and Rothmud–Thomson syndrome, respectively [44, 45]. RecQ helicases are considered to be ‘caretaker’ tumor suppressors which suppress neoplastic transformation through control of chromosomal stability [44]. Figure 5 depicts the members of the RecQ family of DNA helicases from humans, Xenopus, Drosophila, yeast and E. coli. The family contains a highly conserved helicase domain which comprises about 400 amino acids. Two signature motifs are present in most RecQ helicases: the RQC domain and HRDC (helicase and RNaseD C‐terminal) domain (Fig. 5). The RQC domain is unique to RecQ family helicases and probably has a role in mediating interactions with other proteins. The HRDC domain is found in a number of nucleases that digest RNA, and may be involved in DNA binding in RecQ proteins [45]. The members of this family of helicases can unwind many different kinds of structurally diverse DNA substrates, including G4‐DNA (G‐quadruplex DNA) and synthetic Holliday junctions. The BLM and WRN proteins have been shown to promote branch migration of bona fide Holliday junctions generated by the RecA protein [46, 47]. Significantly, this RecQ‐helicase‐catalysed branch migration occurs over several kilobases of DNA, whereas the regular unwinding that is catalysed by these enzymes is only moderately processive and limited to 75–150 bp in the absence of cofactors. This ability to process recombination intermediates formed during DNA replication is proposed to be a key function of the RecQ helicases.

Figure 5.

The RecQ helicase family. Schematic representation of the RecQ family of DNA helicases from human (WRN, BLM, RECQ4, RECQ5, RECQL), Xenopus (FFA‐1, xBLM), Drosophila (DmBLM), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sgs1), Saccharomyces pombe (Rqh1) and E. coli (RecQ). Proteins are aligned by their conserved helicase domains. The size of each protein (in amino acids) is indicated in parentheses under the respective member. The key to various domains is indicated in the box at the bottom. Note: The Drosophila melanogaster RECQ5 and RECQE, Caenorhabditis elegans RecQ5, and RecQ homologs from Arabidopsis thaliana are not shown.

Except for E. coli RecQ, human RECQ5 and RECQL, members of this family are large with extended amino and carboxy ends (Fig. 5). These flanking ends are poorly conserved and are important in functionally distinguishing the roles of the different ‘isoforms’ in humans. WRN helicase differs from the other family of RecQ helicases in containing exonuclease activity as well. The BLM helicase belongs to the family of ring helicases, which includes SV40 large T antigen and E. coli DnaB and RuvB proteins [47]. BLM makes numerous contacts with other proteins. It is a component of ATM kinase, BASC (BRCA1‐associated genome surveillance complex), a multienzyme complex that contains BRCA1 and MLH1, the MRE11–RAD50–NBS1 complex [44]. It has also been shown in a number of studies that WRN interacts physically and functionally with proteins required for DNA replication, including DNA polymerase δ, flap endonuclease 1, PCNA, and RPA [44]. A physical and functional interaction has also been reported for WRN protein and the Ku heterodimer complex, suggesting that WRN protein is also involved in double‐strand break repair [48]. The connection between RecQ homologs and Ku appears to be relevant for telomere maintenance as well. It has been shown that primary fibroblasts from patients with Werner's syndrome, like Ku‐deficient murine cells, display excessive telomere shortening and premature replicative senescence, which is thought to contribute to the early onset of aging seen in Werner's syndrome [49]. However, yeast Sgs1p is also required for a telomere maintenance pathway that is independent of telomerase and dependent on recombination [50]. Thus the RecQ helicases help to define two mechanically distinct telomere maintenance pathways that are both telomerase‐independent and recombination‐dependent.

In a recent study it has been shown that only short DNA duplexes (< 30 bp) can be unwound by RECQ1 alone, but the addition of human replication protein A (hRPA) increases the processivity of the enzyme (> 100 bp). These findings suggest that RECQ1 and hRPA may also interact in vivo and function together in DNA metabolism [51]. RECQ5 is one of the five RecQ helicase homologs identified in humans. Drosophila RECQ5 helicase is capable of unwinding 3′ Flap, three‐way junction, fork and three‐strand junction substrates at lower protein concentrations than 5′ Flap, 12 nucleotide bubble and synthetic Holliday junction structures, which can be unwound efficiently by WRN and BLM [52]. Taken together these findings provide evidence that RecQ helicases facilitate smooth ‘replisome’ progression through the genome. Six cDNAs of RecQ‐like proteins (AtRecQI1, AtRecQI2, AtRecQI3, AtRecQI4A, AtRecQI4B and AtRecQsim) and one gene (AtWRNexo) homologous to the exonuclease domain of human Werner protein have also been isolated from plants [53].

Concluding remarks

The DNA helicases are known to play essential roles in unwinding of duplex strands in almost every aspect of nucleic acid metabolism, which makes them very important molecules. Functional helicases always work as an integrated component of a large macromolecular complex which is ‘designed’ to carry out a particular function on its genomic DNA target. The functions of all reported DNA helicases have not yet been investigated. It will be important to identify and characterize their specific substrates, interacting proteins, and cofactors in order to precisely elucidate their specific functions in nucleic acid metabolism. Despite the diversity of their functions and the large range of organisms in which these proteins have been identified, high sequence conservation is maintained, suggesting that all helicase genes evolved from a common ancestor. The family of DEAD‐box helicases differ mainly in the N‐terminal and C‐terminal sequences, which contain different targeting signals. The different regulatory mechanisms at both the level of expression and post‐transcription may explain the wide spectrum of functions involving DEAD‐box helicases. The crystal structures of DNA helicases suggest that the helicase motifs are clustered together for the overall unwinding function. The motifs, crystal structure, mechanism of unwinding, and various functions of DNA helicases are described in detail in the following review.

The Mcm proteins play an important role in replication by acting as licensing factors, ensuring that replication is not re‐initiated until the first round is completed in one cell cycle. These proteins initiate unwinding at the origin, leading to the formation of a replication bubble. They create a replication fork and move along the fork, at the same time bringing the origin to the unlicensed state. The conservation of Mcms from Archaea to humans suggests that several of these proteins may have evolved from a single progenitor. Helicases of the RecQ family catalyse critical genome maintenance reactions in bacterial and eukaryotic cells, playing key roles in several DNA metabolic processes. Mutations in RecQ genes are linked to genome instability and human disease. As mutants in RecQ family genes have unstable chromosomes, it was proposed that members of the RecQ helicase family play a central role in the maintenance of genomic stability and thereby the prevention of tumorigenesis. A connection between the action of RecQ homologs and gene expression was demonstrated by the involvement of QDE3 of Neurospora crassa in post‐transcriptional gene silencing [54]. However, only one RecQ homolog was found in E. coli and yeast genomes, but multiple homologs are found in the animal and plant kingdom. These homologs of RecQ seem to have evolved first by duplication and then by consecutive shuffling or fusion with other protein domains [54]. Careful genomic studies and further biochemical analysis are needed to understand fully how RecQ DNA helicases influence the processing and/or prevention of recombination intermediates.

Despite considerable progress overall in the helicase field in the last two decades, a large gap in our knowledge persists which prevents complete understanding of the complex genetic processes. Considering the multiplicity of helicases, their tissue specificity, functional diversity, and control of activity by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation, it is reasonable to assume that they also play an important role in cell division, growth, and development. Progress in plant helicases is slow. A better understanding of these proteins will have to await the breakthrough that hopefully will be provided by the high‐resolution structure to be solved by X‐ray crystallography. Furthermore, the RNAi approach and/or transgenic antisense plant technology should help in understanding the detailed role of helicases in plant development.

The number of DNA helicases isolated from all systems is continuously growing. This has created the problem of a bewildering array of different names and classification. Therefore it is important that a clear, scientific system for nomenclature and classification of helicases is formulated. However, this class of proteins does not, at this point, lend itself to a simple method of classification.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr N. S. Mishra and Mr T. Q. Ngoc for their help in preparation of illustrations.

References

- 1.Matson, S.W. (1991) DNA helicases of Escherichia coli. Prog. Nucleic Acids Res. Mol. Biol. 40, 289–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lohman, T.M. (1992) Escherichia coli DNA helicases: mechanisms of DNA unwinding. Mol. Microbiol. 6, 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuteja, N. (2003) Plant DNA helicases: the long unwinding road. J. Exp. Bot. 54, 2201–2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West, S.C. (1996) DNA helicases: new breeds of translocating motors and molecular pumps. Cell 86, 177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuteja, N. & Tuteja, R. (1996) DNA helicases: the long unwinding road. Nat. Genet. 13, 11–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorbalenya, A.E. , Koonin, E.V. , Donchenko, A.P. & Blinov, V.M. (1988) A novel superfamily of nucleoside triphosphate‐binding motif containing proteins which are probably involved in duplex unwinding in DNA and RNA replication and recombination. FEBS Lett. 235, 16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linder, P. , Lasko, P.F. , Ashburner, M. , Leroy, P. , Nielsen, P.J. , Nishi, K. , Schneir, J. & Slonimski, P.P. (1989) Birth of the DEAD‐box. Nature (London) 337, 121–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanner, N.K. , Cordin, O. , Banroques, J. , Doère, M. & Linder, P. (2003) The Q MOTIF: a newly identified motif in DEAD box helicases may regulate ATP binding and hydrolysis. Mol. Cell 11, 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdel‐Monem, M. , Durwald, H. & Hoffmann‐Berling, H. (1976) Enzymic unwinding of DNA. II. Chain separation by an ATP‐dependent DNA unwinding enzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 65, 441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hotta, Y. & Stern, H. (1978) DNA unwinding protein from meiotic cells of Lilium. Biochemistry 17, 1872–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkatesan, M. , Silver, I.L. & Nossal, N.G. (1982) Bacteriophage T4 gene 41 protein, required for the synthesis of RNA primers, is also a DNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 12426–12434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matson, S.W. , Tabor, S. & Richardson, C.C. (1983) The gene 4 protein of bacteriophage T7. Characterization of helicase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 14017–14024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amaratunga, M. & Lohman, T.M. (1993) E. coli rep helicase unwinds DNA by an active mechanism. Biochemistry 32, 6815–6820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raney, K.D. , Sowers, L.C. , Millar, D.P. & Benkovic, S.J. (1994) A fluorescence‐based assay for monitoring helicase activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 6644–6648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sivaraja, M. , Giordano, H. & Peterson, M.G. (1998) High‐throughput screening assay for helicase enzymes. Anal. Biochem. 265, 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kyono, K. , Miyashiro, M. & Taguchi, I. (1998) Detection of hepatitis C virus helicase activity using the scintillation proximity assay system. Anal. Biochem. 257, 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Earnshaw, D.L. , Moore, K.J. , Greenwood, C.J. , Djaballah, H. , Jurewicz, A.J. , Murray, K.J. & Pope, A.J. (1999) Time‐resolved fluorescence energy transfer DNA helicase assays for throughput screening. J. Biomol. Screening 4, 239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hicham Alaoui‐Ismaili, M. , Gervais, C. , Brunette, S. , Gouin, G. , Hamel, M. , Rando, R.F. & Bedard, J. (2000) A novel high throughput screening assay for HCV NS3 helicase activity. Antiviral Res. 46, 181–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang, L. , Schwartz, G. , O'Donnell, M. & Harrison, R. (2001) Development of a novel helicase assay using electrochemiluminescence. Anal. Biochem. 293, 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu, H.Q. , Zhang, A.H. , Auclair, C. & Xi, X.G. (2003) Simultaneously monitoring DNA binding and helicase‐catalyzed DNA unwinding by fluorescence polarization. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsaneva, I.R. , Muller, B. & West, S.C. (1993) RuvA and RuvB proteins of Escherichia coli exhibit DNA helicase activity in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 1315–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitby, M.C. , Vincent, S.D. & Lloyd, R.G. (1994) Branch migration of Holliday junctions: identification of RecG protein as a junction specific DNA helicase. EMBO J. 13, 5220–5228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bujalowski, W. & Jezewska, M.J. (1995) Interactions of Escherichia coli primary replicative helicase DnaB protein with single‐stranded DNA. The nucleic acid does not wrap around the protein hexamer. Biochemistry 34, 8513–8519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singleton, M.R. , Sawaya, M.R. , Ellenberger, T. & Wigley, D.B. (2000) Crystal structure of T7 gene 4 ring helicase indicates a mechanism for sequential hydrolysis of nucleotides. Cell 101, 589–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dillingham, M.S. , Spies, M. & Kowalczykowski, S.C. (2003) RecBCD enzyme is a bipolar DNA helicase. Nature (London) 423, 893–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naqvi, A. , Tinsley, E. & Khan, S.A. (2003) Purification and characterization of the PcrA helicase of Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 185, 6633–6639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Constantinesco, F. , Forterre, P. , Koonin, E.V. , Aravind, L. & Elie, C.A. (2004) Bipolar DNA helicase gene, herA, clusters with rad50, mre11 and nurA genes in thermophilic archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1439–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delagoutte, E. & von Hippel, P.H. (2002) Helicase mechanisms and the coupling of helicases within macromolecular machines. Part I. Structures and properties of isolated helicases. Q. Rev. Biophys. 35, 431–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris, P.D. , Tackett, A.J. , Babb, K. , Nanduri, B. , Chick, C. , Scott, J. & Raney, K.D. (2001) Evidence for a functional monomeric form of the bacteriophage T4 DdA helicase. DdA does not form stable oligomeric structures. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19691–19698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pham, X.H. , Reddy, M.K. , Ehtesham, N.Z. , Matta, B. & Tuteja, N. (2000) A DNA helicase from Pisum sativum is homologous to translation initiation factor and stimulates topoisomerase I activity. Plant J. 24, 219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tuteja, N. , Beven, A.F. , Shaw, P.J. & Tuteja, R. (2001) A pea homologue of human DNA helicase I is localized within the dense fibrillar component of the nucleolus and stimulated by phosphorylation with CK2 and cdc2 protein kinases. Plant J. 25, 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mechanic, L.E. , Hall, M.C. & Matson, S.W. (1999) Escherichia coli DNA helicase II is active as a monomer. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 12288–12498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ayora, S. , Weise, F. , Mesa, P. , Stasiak, A. & Alonso, J.C. (2002) Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage SPP1 hexameric DNA helicase, G40P, interacts with forked DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 2280–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tuteja, R. , Malhotra, P. , Song, P. , Tuteja, N. & Chauhan, V.S. (2002) Isolation and characterization of eIF‐4A homologue from Plasmodium cynomolgi. Mol. Biol. Parasitol. 124, 79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuteja, R. , Tuteja, N. , Malhotra, P. & Chauhan, V.S. (2003) Replication fork stimulated eIF‐4A from Plasmodium cynomolgi unwinds DNA in the 3′ to 5′ direction and is inhibited by DNA‐interacting compounds. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 414, 108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Labib, K. , Tercero, J.A. & Diffley, J.F. (2000) Uninterrupted MCM2‐7 function required for DNA replication fork progression. Science 288, 1643–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishimi, Y. (1997) A DNA helicase activity is associated with an MCM4‐6, and ‐7 protein complex. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 24508–24513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee, J.K. & Hurwitz, J. (2001) Processive DNA helicase activity of the minichromosome maintenance proteins 4, 6, and 7 complex requires forked DNA structures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 54–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaarschmidt, D. , Ladenburger, E.M. , Keller, C. & Knippers, R. (2002) Human Mcm proteins at a replication origin during the G1 to S phase transition. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 4176–4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lei, M. , Kawasaki, Y. , Young, M.R. , Kihara, M. , Sugino, A. & Tye, B.K. (1997) Mcm2 is a target of regulation by Cdc‐7‐Dbf4 during the initiation of DNA synthesis. Genes Dev. 11, 3365–3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson, E.M. , Kinoshita, Y. & Daniel, D.C. (2003) A new member of the MCM protein family encoded by the human MCM8 gene, located contrapodal to GCD10 at chromosome band 20p12.3–13. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 2915–2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakayama, H. , Nakayama, K. , Nakayama, R. , Irino, N. , Nakayama, Y. & Hanawalt, P.C. (1984) Isolation and genetic characterization of a thymineless death‐ resistant mutant of Escherichia coli K12: identification of a new mutation (rec Q) that blocks the Rec F recombination pathway. Mol. Gen. Genet. 195, 474–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Umezu, K. , Nakayama, K. & Nakayama, H. (1990) Escherichia coli RecQ protein is a DNA helicase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 87, 5363–5364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hickson, I.D. (2003) RecQ helicase: caretakers of the genome. Nat. Rev. 3, 169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu, Z. , MacIas, M.J. , Bottomley, M.J. , Stier, G. , Linge, J.P. , Nilges, M. , Bork, P. & Sattler, M. (1999) The three‐dimensional structure of the HRDC domain and implications for the Werner and Bloom syndrome proteins. Struct. Fold Des. 7, 1557–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Constantinou, A. , Tarsounas, M. , Karow, J.K. , Brosh, R.M. , Bohr, V.A. , Hickson, I.D. & West, S.C. (2000) Werner's syndrome protein (WRN) migrates Holliday junctions and co‐localizes with RPA upon replication arrest. EMBO Rep. 1, 80–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karow, J.K. , Constantinou, A. , Li, J.L. , West, S.C. & Hickson, I.D. (2000) The Bloom's syndrome gene product promotes branch migration of Holliday junctions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6504–6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li, B.M. & Comai, L. (2000) Functional interaction between Ku and the Werner syndrome protein in DNA end processing. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 28349–28352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nehlin, J.O. , Skovgaard, G.L. & Bohr, V.A. (2000) The Werner syndrome. A model for the study of human aging. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 908, 167–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang, P. , Pryde, F.E. , Lester, D. , Maddison, R.L. , Borts, R.H. , Hickson, I.D_et al._ (2001) SGS1 is required for telomere elongation in the absence of telomerase. Curr. Biol. 11, 125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cui, S. , Klima, R. , Ochem., A. , Arosio, D. , Falaschi, A. & Vindigni, A. (2003) Characterization of the DNA‐unwinding activity of human RECQ1, a helicase specifically stimulated by human replication protein A. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1424–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ozsoy, A.Z. , Ragonese, H.M. & Matson, S.W. (2003) Analysis of helicase activity and substrate specificity of Drosophila RECQ5. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 1554–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hartung, F. , Plchova, H. & Puchta, H. (2000) Molecular characterisation of RecQ homologues in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 4275–4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cogoni, C. & Macino, G. (1999) Posttranscriptional gene silencing in Neurospora by a RecQ DNA helicase. Science 286, 2343–2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watson, J.D. & Crick, F.H.C. (1953) Molecular structure of nucleic acids. Nature (London) 191, 737–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Denhardt, D.T. , Dressler, D.H. & Hathaway, A. (1967) The abortive replication of NX174 DNA in a recombination‐deficient mutant of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 57, 813–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yarranton, G.T. & Gefter, M.L. (1979) Enzyme catalyzed DNA unwinding: studies on Escherichia coli rep protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 76, 1658–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hubscher, U. & Stalder, H.P. (1985) Mammalian DNA helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 13, 5471–5483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stahl, H. , Droge, P. & Knippers, R. (1986) DNA helicase activity of SV40 large tumor antigen. EMBO J. 5, 1939–1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sugino, A. , Bung, H.R. , Sugino, T. , Naumovski, L. & Friedberg, E.C. (1986) A new DNA‐dependent ATPase which stimulates yeast DNA polymerase I and has DNA‐unwinding activity. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 11744–11750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hodgeman, T.C. (1988) A new superfamily of replicative proteins. Nature (London) 333, 22–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gorbalenya, A.E. , Koonin, E.V. , Donchenko, A.P. & Blinov, V.M. (1989) Two related superfamilies of putative helicases involved in replication, recombination, repair and expression DNA and RNA genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 4713–4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tuteja, N. , Tuteja, R. , Rahman, K. , Kang, L.‐Y. & Falaschi, A. (1990) A DNA helicase from human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 6785–6792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hehman, G.L. & Hauswirth, W.W. (1992) DNA helicase from mammalian mitochondria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 8562–8566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tuteja, N. , Phan, T.N. & Tewari, K.K. (1996) Purification and characterization of a DNA helicase from pea chloroplast that translocates in the 3′‐to‐5′ direction. Eur. J. Biochem. 238, 54–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Subramanya, H.S. , Bird, L.E. , Brannigan, J.A. & Wigley, D.B. (1996) Crystal structure of a DExx box DNA helicase. Nature (London) 384, 379–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gray, M.D. , Shen, J.C. , Kamath‐Loeb, A.S. , Blank, A. , Sopher, B.L. , Martin, G.M. , Oshma, J. & Loeb, L.A. (1997) The Werner syndrome protein is a DNA helicase. Nat. Genet. 17, 100–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karow, J.K. , Chakraverty, R.K. & Hickson, R.D. (1997) The Bloom's syndrome gene product is a 3′‐5′ DNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 30611–30614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bennett, R.J. , Sharp, J.A. & Wang, J.C. (1998) Purification and characterization of the Sgs1 DNA helicase activity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9644–9650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lal, S.K. , Giroux, M.J. , Brendel, V. , Vallejos, C.E. & Hannah, L.C. (2003) The maize genome contains a Helitron insertion. Plant Cell 15, 381–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lebowitz, J.H. & Mcmacken, R. (1986) The Escherichia coli dnaB replication protein is a DNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 4738–4748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee, M.S. & Marians, K. (1990) Differential ATP requirements distinguish the DNA translocation and DNA unwinding activities of the Escherichia coli Pri A protein. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 17078–17083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oh, E.Y. & Grossman, L. (1989) Characterization of the helicase activity of the Escherichia coli UvrAB protein. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 1336–1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Theis, K. , Chen, P.J. , Skorvaga, M. , Van Houten, B. & Kisker, C. (1999) Crystal structure of UvrB, a DNA helicase adapted for nucleotide excision repair. EMBO J. 18, 6899–6907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Runyon, G.T. , Bear, D.G. & Lohman, T.M. (1990) Escherichia coli helicase II (UvrD) protein initiates DNA unwinding at nicks and blunt ends. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 87, 6383–6387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roman, L.J. & Kowalczykowski, S.C. (1989) Characterization of the helicase activity of the E. coli RecBCD enzyme using a novel helicase assay. Biochemistry 28, 2863–2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Whitby, M.C. & Lloyd, R.G. (1995) Branch migration of three‐strand recombination intermediates by RecG, a possible pathway for securing exchanges initiated by 3′‐tailed duplex DNA. EMBO J. 14, 3302–3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Voloshin, O.N. , Vanevski, F. , Khil, P.P. & Camerini‐Otero, R.D. (2003) Characterization of the DNA damage‐inducible helicase DinG from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28284–28293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jones, C.E. , Mueser, T.C. , Dudas, K.C. , Kreuzer, K.N. & Nossal, N.G. (2001) Bacteriophage T4 gene 41 helicase and gene 59 helicase‐loading protein: a versatile couple with roles in replication and recombination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 8312–8318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jongeneel, C.V. , Formosa, T. & Alberts, B.M. (1984) Purification and characterization of the bacteriophage T4 dda protein. A DNA helicase that associates with the viral helix‐destabilizing protein. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 12925–12932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carles‐Kinch, K. , George, J.W. & Kreuzer, K.N. (1997) Bacteriophage T4 UvsW protein is a helicase involved in recombination, repair and the regulation of DNA replication origins. EMBO J. 16, 4142–4151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Patel, S.S. , Rosenberg, A.H. , William‐Studier, F. & Johnson, K.A. (1992) Large scale purification and biochemical characterization of T7 primase/helicase proteins. Evidence for homodimer and heterodimer formation. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 15013–15021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ziegelin, G. , Scherzinger, E. , Lurz, R. & Lanka, E. (1993) Phage P4 α protein is multifunctional with origin recognition, helicase and primase activities. EMBO J. 12, 3703–3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Goetz, G.S. , Dean, F.B. , Hurwitz, J. & Matson, S.W. (1988) The unwinding of duplex regions in DNA by the simian virus 40 large tumor antigen‐associated DNA helicase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 383–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Seki, M. , Enomoto, T. , Eki, T. , Miyajima, A. , Murakami, Y. , Hanaoka, F. & Ui, M. (1990) DNA helicase and nucleoside‐5′‐ triphosphatase activities of polioma virus large tumor antigen. Biochemistry 29, 1003–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Crute, J.J. , Bruckner, R.C. , Dodson, M.S. & Lehman, I.R. (1991) Herpes simplex‐I helicase‐primase. Identification of two nucleoside triphosphatase sites that promote DNA helicase action. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 21252–21256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Boehmer, P.E. , Dodson, M.S. & Lehman, I.R. (1993) The herpes simplex virus type‐1 origin binding protein. DNA helicase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 1220–1225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.SEO, Y.‐S. , Müller, F. , Lusky, M. & Hurwitz, J. (1993) Bovine papilloma viral (BPV)‐encoded E1 protein contains multiple activities required for PBV DNA replication. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 702–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Im, D.S. & Muzyczka, N. (1992) Partial purification of adeno‐associated virus Rep78, Rep52, and Rep40 and their biochemical characterization. J. Virol. 66, 1119–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wilson, G.M. , Jindal, H.K. , Yeung, D.E. , Chen, W. & Astell, C.R. (1991) Expression of minute virus of mice major nonstructural protein in insect cells: purification and identification of ATPase and helicase activities. Virology 185, 90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mcdougal, V.V. & Guarino, L.A. (2000) The Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus p143 gene encodes a DNA helicase. J. Virol. 74, 5273–5279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Simpson, D.A. & Condit, R.C. (1995) Vaccinia virus gene A18R encodes an essential DNA helicase. J. Virol. 69, 6131–6139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tanner, J.A. , Watt, R.M. , Chai, Y.B. , Lu, L.Y. , Lin, M.C. , Peiris, J.S. , Poon, L.L. , Kung, H.F. & Huang, J.D. (2003) The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus NTPase/helicase belongs to a distinct class of 5′‐to 3′ viral helicases. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 39578–39582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sung, P. , Prakash, L. , Matson, S.W. & Prakash, S. (1987) RAD3 protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a DNA helicase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 84, 8951–8955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Guzder, S.N. , Sung, P. , Bailly, V. , Prakash, L. & Prakash, S. (1994) RAD25 is a DNA helicase required for DNA repair and RNA polymerase II transcription. Nature (London) 369, 578–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rong, L. & Klein, H.L. (1993) Purification and characterization of the SRS2 DNA helicase of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 1252–1259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lahaye, A. , Sahl, H. , Thines‐Sempoux, D. & Foury, F. (1991) pif1: a DNA helicase in yeast mitochondria. EMBO J. 10, 997–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Biswas, E.E. , Chen, P.H. & Biswas, S.B. (1993) DNA helicase associated with DNA polymerase alpha: isolation by a modified immunoaffinity chromatography. Biochemistry 32, 13393–13398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Biswas, E.E. , Chen, P.H. , Leszyk, J. & Biswas, S.B. (1995) Biochemical and genetic characterization of a replication protein A dependent DNA helicase from the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 206, 850–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li, X. , Tao, C.K. , So, A.G. & Downey, K.M. (1992) Purification and characterization of delta helicase from fetal calf thymus. Biochemistry 31, 3507–3513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bean, D.W. , Kallam, W.E. & Matson, S.W. (1993) Purification and characterization of a DNA helicase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 21783–21790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Shimizu, K. & Sugino, A. (1993) Purification and characterization of DNA helicase III from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 9578–9584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lee, C. & Seo, Y.S. (1998) Isolation and characterization of a processive DNA helicase from fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe that translocates in a 5′‐to 3′ direction. Biochem. J. 334, 377–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nakagawa, T. , Flores‐Rozas, H. & Kolodner, R.D. (2001) The MER3 helicase involved in meiotic crossing over is stimulated by single‐stranded DNA binding proteins and unwinds DNA in the 3′ to 5′ direction. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31487–31493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sedman, T. , Kuusk, S. , Kivi, S. & Sedman, J. (2000) A DNA helicase required for maintenance of the functional mitochondrial genome in Saccharomyces cereviseae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1816–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cannon, G.C. & Heinhorst, S. (1990) Partial purification and characterization of DNA helicase from chloroplast of Glycine max. Plant Mol. Biol. 15, 457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tamura, K. , Adachi, Y. , Chiba, K. , Oguchi, K. & Takahashi, H. (2002) Identification of Ku70 and Ku80 homologues in Arabidopsis thaliana: evidence for a role in repair of double‐strand breaks. Plant J. 29, 771–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Thömmes, P. , Ferrari, E. , Jessberger, R. & Hubscher, U. (1992) Four different DNA helicases from calf thymus. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 6063–6073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Siegal, G. , Turchi, J.J. , Jessee, C.B. , Myers, T.W. & Bambara, R.A. (1992) A novel DNA helicase from calf thymus. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 13629–13635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Georgaki, A. , Tuteja, N. , Sturzenegger, B. & Hubscher, U. (1994) Calf thymus DNA helicase F, a replication protein A copurifying enzyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 1128–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang, S. & Grosse, F. (1991) Purification and characterization of two DNA helicases from calf thymus nuclei. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 20483–20490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhang, S. & Grosse, F. (1992) Isolation and characterization of a DNA helicase from cytosolic extracts of calf thymus. Chromosoma 102, S 100–106.81. Seo, Y‐S. & Hurwitz, J. (1993) Isolation of helicase α, a DNA helicase from HeLa cells stimulated by fork structure and single‐stranded DNA binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 10282–10295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tuteja, N. , Tuteja, R. , Ochem., A. , Taneja, P. , Huang, N.W. , Simoncsits, A. , Susic, S. , Rahman, K. , Marusic, L. , Chen, J. , Zhang, J. , Wang, S. , Pongor, S. & Falaschi, A. (1994) Human DNA helicase II: a novel DNA unwinding enzyme identified as the Ku autoantigen. EMBO J. 13, 4991–5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Costa, M. , Ochem., A. , Staub, A. & Falaschi, A. (1999) Human DNA helicase VIII: a DNA and RNA helicase corresponding to the G3 BP protein, an element of the ras transduction pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 817–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sung, P. , Baily, V. , Weber, C. , Thompson, L.H. , Prakash, L. & Prakash, S. (1993) Human Xeroderma pigmentosum group D gene encodes a DNA helicase. Nature (London) 365, 852–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Schaeffer, L. , Roy, R. , Humbert, S. , Moncollin, V. , Vermeulen, W. , Hoeijmakers, J.H.J. , Chambon, P. & Egly, J.‐M. (1993) DNA repair helicase: a component of BTF2 (TFIIH) basic transcription factor. Science 260, 58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Seo, Y.‐S. , Lee, S.H. & Hurwitz, J. (1991) Isolation of a helicase from Hela cells requiring the multisubunit human single‐stranded DNA‐binding protein for activity. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 13161–13170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Seo, Y.‐S. & Hurwitz, J. (1993) Isolation of helicase α, a DNA helicase from HeLa cells stimulated by fork structure and single‐stranded DNA binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 10282–10295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Dailey, L. , Caddle, M.S. , Heintz, N. & Heintz, H. (1990) Purification of RIP60 and RIP100, mammalian proteins with origin‐specific DNA binding and ATP‐dependent DNA helicase activities. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 6225–6235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Seki, M. , Yanagisawa, J. , Kohda, T. , Sonoyama, T. , Ui, M. & Enomoto, T. (1994) Purification of two DNA‐dependent adenosine triphosphatases having DNA helicase activity from HeLa cells and comparison of properties of two enzymes. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 115, 523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hirota, Y. & Lahti, J.M. (2000) Characterization of enzymatic activity of hCh1R1, a novel human DNA helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 917–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Biswas, E.E. , Nagele, R.G. & Biswas, S.B. (2001) A novel human hexameric DNA helicase: expression, purification and characterization. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 1733–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Shen, J.C. , Gray, M.D. , Oshima, J. & Loeb, L.A. (1998) Characterization of Werner Syndrome protein DNA helicase activity: directionality, substrate dependence and stimulation by replication protein A. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 2879–2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ellis, N.A. (1997) DNA helicase in inherited human disorders. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 7, 354–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Marini, F. & Wood, R.D. (2002) A human DNA helicase homologous to the DNA cross‐link sensitivity protein Mus308. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 8716–8723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kim, J. , Kim, J.H. , Lee, S.H. , Kim, D.H. , Kang, H.Y. , Bae, S.H. , Pan, Z.Q. & Seo, Y.S. (2002) The novel human DNA helicase hFDH is an F‐box protein. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 24530–24537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Cantor, S. , Drapkin, R. , Zhang, F. , Lin, Y. , Han, J. , Pamidi, S. & Livingston, D.M. (2004) The BRCA1‐associated protein BACH1 is a DNA helicase targeted by clinically relevant inactivating mutations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 2357–2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]