Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: pathophysiological, genetic, and therapeutic insights: a consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel (original) (raw)

Abstract

Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) starts early, even in childhood.1,2 Non-invasive imaging in the PESA (Progression of Early Subclinical Atherosclerosis) study revealed that 71% and 43% of middle-aged men and women, respectively, have evidence of subclinical atherosclerosis.3 Extensive evidence from epidemiologic, genetic, and clinical intervention studies has indisputably shown that low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is causal in this process, as summarized in the first Consensus Statement on this topic.4 What are the key biological mechanisms, however, that underlie the central role of LDL in the complex pathophysiology of ASCVD, a chronic and multifaceted lifelong disease process, ultimately culminating in an atherothrombotic event?

This second Consensus Statement on LDL causality discusses the established and newly emerging biology of ASCVD at the molecular, cellular, and tissue levels, with emphasis on integration of the central pathophysiological mechanisms. Key components of this integrative approach include consideration of factors that modulate the atherogenicity of LDL at the arterial wall and downstream effects exerted by LDL particles on the atherogenic process within arterial tissue.

Although LDL is unequivocally recognized as the principal driving force in the development of ASCVD and its major clinical sequelae,4,5 evidence for the causal role of other apolipoprotein B (apoB)-containing lipoproteins in ASCVD is emerging. Detailed consideration of the diverse mechanisms by which these lipoproteins, including triglyceride (TG)-rich lipoproteins (TGRL) and their remnants [often referred to as intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL)], and lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)], contribute not only to the underlying pathophysiology of ASCVD but also potentially to atherothrombotic events, is however beyond the focus of this appraisal.6–14

The pathophysiological and genetic components of ASCVD are not fully understood. We have incomplete understanding, for example, of factors controlling the intimal penetration and retention of LDL, and the subsequent immuno-inflammatory responses of the arterial wall to the deposition and modification of LDL. Disease progression is also affected by genetic and epigenetic factors influencing the susceptibility of the arterial wall to plaque formation and progression. Recent data indicate that these diverse pathophysiological aspects are key to facilitating superior risk stratification of patients and optimizing intervention to prevent atherosclerosis progression. Moreover, beyond atherosclerosis progression are questions relating to mechanisms of plaque regression and stabilization induced following marked LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) reduction by lipid-lowering agents.15–19 Finally, the potential implication of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and its principal protein, apoAI, as a potential modulator of LDL atherogenicity remains unresolved.20 It was, therefore, incumbent on this Consensus Panel to identify and highlight the missing pieces of this complex puzzle as target areas for future clinical and basic research, and potentially for the development of innovative therapeutics to decrease the burgeoning clinical burden of ASCVD.

Trancytosis of low-density lipoprotein across the endothelium

Apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins of up to ∼70 nm in diameter [i.e. chylomicron remnants, very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) and VLDL remnants, IDL, LDL, and Lp(a)] can cross the endothelium (Figure 1).21–29 Low-density lipoprotein, as the most abundant atherogenic lipoprotein in plasma, is the key deliverer of cholesterol to the artery wall. Many risk factors modulate the propensity of LDL and other atherogenic lipoproteins to traverse the endothelium and enter the arterial intima.30 Despite the relevance of LDL endothelial transport during atherogenesis, however, the molecular mechanisms controlling this process are still not fully understood.31

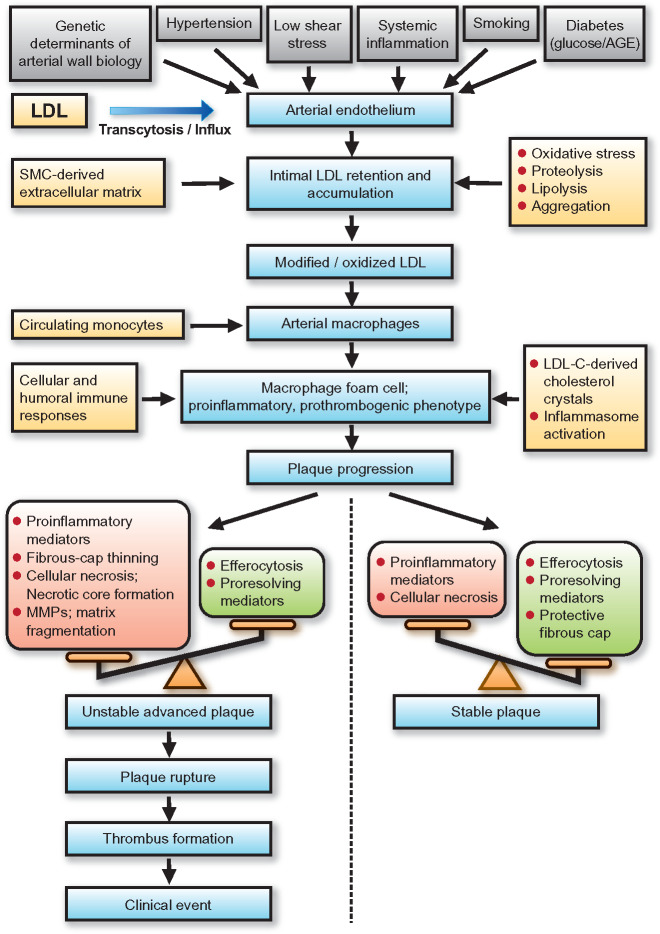

Figure 1.

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) as the primary driver of atherogenesis. Key features of the influx and retention of LDL in the arterial intima, with ensuing pathways of modification leading to (i) extracellular cholesterol accumulation and (ii) formation of cholesteryl ester droplet-engorged macrophage foam cells with transformation to an inflammatory and prothrombotic phenotype. Both of these major pathways favour formation of the plaque necrotic core containing cellular and extracellular debris and LDL-cholesterol-derived cholesterol crystals. CE, cholesteryl ester; DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns; ECM, extracellular matrix; FC, free cholesterol; GAG, glycosaminoglycans; PG, proteoglycans; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

A considerable body of evidence in recent years32 has challenged the concept that movement of LDL occurs by passive filtration (i.e. as a function of particle size and concentration) across a compromised endothelium of high permeability.33 Studies have demonstrated that LDL transcytosis occurs through a vesicular pathway, involving caveolae,34–36 scavenger receptor B1 (SR-B1),37 activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1),38 and the LDL receptor.32 However, although the LDL receptor appears to mediate LDL transcytosis across the blood–brain barrier,39 proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9)-directed degradation of the LDL receptor has no effect on LDL transcytosis40; thus, LDL transport across the endothelium in the systemic circulation seems to be LDL receptor-independent.32 Indeed, new evidence shows that LDL transcytosis across endothelial cell monolayers requires interaction of SR-B1 with a cytoplasmic protein.40 More specifically, LDL induces a marked increase in the coupling of SR-B1 (through an eight-amino-acid cytoplasmic tail domain) to the guanine nucleotide exchange factor dedicator of cytokinesis 4 (DOCK4); both SR-B1 and DOCK4 are required for LDL transport.41 Interestingly, expression of SR-B1 and DOCK4 is higher in human atherosclerotic arteries than in normal arteries.41

Oestrogens significantly inhibit LDL transcytosis by down-regulating endothelial SR-BI.42 This down-regulation is dependent on the G-protein-coupled oestrogen receptor and explains why physiological levels of oestrogen reduce LDL transcytosis in arterial endothelial cells of male but not female origin. These findings offer one explanation for why women have a lower risk than men of ASCVD before but not after the menopause.43,44 Transcytosis of LDL across endothelial cells can also be increased, for example, by activation of the NOD-like receptor containing domain pyrin 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome,45 the multiprotein cytosolic complex that activates expression of the interleukin-1 (IL-1) family of cytokines, or by hyperglycaemia.46 In contrast, rapid correction of hypercholesterolaemia in mice improved the endothelial barrier to LDL.47 The mechanisms that underlie increased rates of LDL transcytosis during hypercholesterolaemia remain unclear; improved understanding offers potential for therapies targeting early events in atherosclerosis.48

Factors affecting retention of low-density lipoprotein in the artery wall

Subendothelial accumulation of LDL at lesion-susceptible arterial sites is mainly due to selective retention of LDL in the intima, and is mediated by interaction of specific positively charged amino acyl residues (arginine and lysine) in apoB100 with negatively charged sulfate and carboxylic acid groups of arterial wall proteoglycans.49 Genetic alteration of either the proteoglycan-binding domain of apoB100 or the apoB100-binding domain of arterial wall proteoglycans greatly reduces atherogenesis.49,50 Thus, the atherogenicity of LDL is linked to the ability of its apoB100 moiety to interact with arterial wall proteoglycans,50,51 a process influenced by compositional changes in both the core and surface of the LDL particle. For example, enrichment of human LDL with cholesteryl oleate enhances proteoglycan-binding and atherogenesis.52 In addition, apoE, apoC-III, and serum amyloid A increase the affinity of LDL for arterial wall proteoglycans.49,53–55

Autopsy studies in young individuals demonstrated that atherosclerosis-prone arteries develop intimal hyperplasia, a thickening of the intimal layer due to accumulation of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) and proteoglycans.56,57 In contrast, atherosclerosis-resistant arteries form minimal to no intimal hyperplasia.57–59 Surgical induction of disturbed laminar flow in the atherosclerosis-resistant common carotid artery of mice has been shown to cause matrix proliferation and lipoprotein retention,60 indicating that hyperplasia is critical to the sequence of events leading to plaque formation.

Although the propensity to develop atherosclerosis varies markedly across different sites in the human vasculature, it is notable at branches and bifurcations where the endothelium is exposed to disturbed laminar blood flow and low or fluctuating shear stress.61 These mechanical forces may modulate gene and protein expression and induce endothelial dysfunction and intimal hyperplasia. Formation of atherosclerotic lesions in vessels exhibiting intimal hyperplasia also occurs following surgical intervention, as exemplified by vascular changes following coronary artery bypass surgery.62 A number of the genetic variants strongly associated with ASCVD in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) occur in genes that encode arterial wall proteins, which either regulate susceptibility to LDL retention or the arterial response to LDL accumulation.63 This topic is discussed in more detail below.

Low-density lipoprotein particle heterogeneity

Low-density lipoprotein particles are pseudomicellar, quasi-spherical, and plurimolecular complexes. The lipidome accounts for ∼80% by weight and involves >300 distinct molecular species of lipids (Meikle and Chapman, unpublished observations), whereas the proteome is dominated by apoB100 (one molecule per LDL particle).64–66 ApoB100, one of the largest mammalian proteins (∼550 kDa), maintains the structural integrity of particles in the VLDL-LDL spectrum and, in contrast to smaller apolipoproteins, remains with the lipoprotein particle throughout its life cycle.

At circulating particle concentrations of ∼1 mmol/L, LDL is the principal carrier of cholesterol (2000–2700 molecules per particle, of which ∼1700 are in esterified form) in human plasma. Low-density lipoprotein is also the major carrier of vitamin E, carotenoids, and ubiquinol, but a minor carrier of small, non-coding RNAs compared with HDL, although the proatherogenic microRNA miR-155 is abundant in LDL.66–68

Low-density lipoprotein comprises a spectrum of multiple discrete particle subclasses with different physicochemical, metabolic, and functional characteristics (Box 1).64,66,67,69–84,90–98 In people with normal lipid levels, three major subclasses are typically recognized: large, buoyant LDL-I (density 1.019–1.023 g/mL), LDL-II of intermediate size and density (density 1.023–1.034 g/mL), small dense LDL-III (density 1.034–1.044 g/mL); and a fourth subfraction of very small dense LDL-IV (density 1.044–1.063 g/mL) is present in individuals with elevated TG levels 64,75,81,90,99 Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol measured routinely in the clinical chemistry laboratory is the sum of cholesterol in these subclasses and in IDL and Lp(a).100,101

Box 1.

Differences in physicochemical, metabolic, and functional characteristics between the markedly heterogenous low-density lipoprotein subclasses

- Particle diameter, molecular weight, hydrated density, net surface charge, % weight lipid and protein composition (CE, FC, TG, PL, and PRN), and N-linked glycosylation of apoB100.

- Particle origin (liver and intravascular remodelling from precursor particles).

- Residence time in plasma (turnover half-life).

- Relative binding affinity for the cellular LDL receptor.

- Conformational differences in apoB100.

- Relative susceptibility to oxidative modification under oxidative stress (e.g. conjugated diene and LOOH formation).

- Relative binding affinity for arterial wall matrix proteoglycans and thus potential for arterial retention.

- Relative content of minor apolipoproteins, including apoC-III and apoE.

- Relative content of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2.

- Relative acceptor activities for neutral lipid transfer/exchange (CE and TG) mediated by CETP.

apo, apolipoprotein; CE, cholesteryl ester; CETP, cholesteryl ester transfer protein; FC, free cholesterol; LOOH, lipid hydroperoxide; PL, phospholipid; PRN, protein; TG, triglyceride.

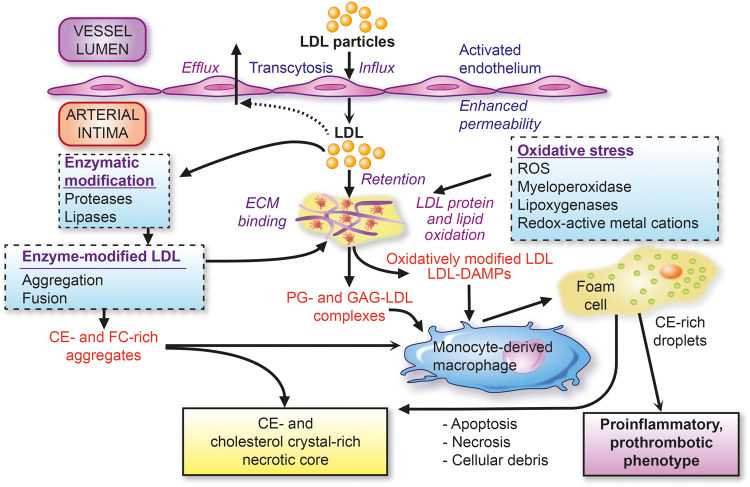

Factors affecting the low-density lipoprotein subfraction profile

Very low-density lipoprotein-TG levels are a major determinant of the LDL subfraction profile. As plasma TG levels rise, the profile shifts from a predominance of large particles to small dense LDL.64,66,74,77–79,90,99 Sex is also a key factor; men are more likely to produce small dense LDL than women at a given TG level, with the underlying mechanism attributed to higher hepatic lipase activity.74,79,90 In metabolic models explaining the generation of small LDL species (LDL-III and LDL-IV), cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP)-mediated transfer of TG molecules from VLDL (and potentially chylomicrons) to the core of LDL particles in exchange for cholesteryl esters is a critical step.102 The LDL particle may be subsequently lipolyzed by hepatic lipase to remove both TG from the core and phospholipid from the surface, thereby producing a new, stable but smaller and denser particle.64,74,75,79

Plasma TG levels in the fasting state are regulated by VLDL production in the liver, residual intestinal production of apoB48-containing VLDL-sized particles,103 the activities of lipoprotein and hepatic lipases, and the rate of particle clearance by receptor-mediated uptake. The liver can produce a range of particles varying in size from large VLDL1, medium-sized VLDL2, to LDL, depending on hepatic TG availability.92 The rate of VLDL production is also influenced by metabolic factors, such as insulin resistance, and lipolysis and clearance of VLDL are markedly affected by apoC-III and angiopoietin-like 3 (ANGPTL3) content and lipase activities.91,94 The LDL subclass profile is principally determined by the nature of the secreted VLDL particles, their circulating concentrations, the activities of lipases and neutral lipid transfer proteins including CETP, tissue LDL receptor activity, and the affinity of LDL particles to bind to the receptor, which is, in turn, a function of the conformation of apoB100 within the particle.69,104,105 These factors are critical determinants of the amount and overall distribution of LDL particle subclasses, as well as their lipidomic profile and lipid load.64,69,70,74,75

Individuals with plasma TG in the range 0.85–1.7 mmol/L (75–150 mg/dL) release VLDL1 and VLDL2 from the liver,91,93 which are delipidated rapidly to IDL and then principally to LDL of medium size;64,66,99 thus, the LDL profile is dominated by LDL-II (Figure 2A). In contrast, people with low plasma TG levels (<0.85 mmoL/L or 75 mg/dL) have highly active lipolysis and generally low hepatic TG content. Consequently, hepatic VLDL tend to be smaller and indeed some IDL/LDL-sized particles are directly released from the liver.74–76 The LDL profile displays a higher proportion of larger LDL-I (_Figure 2B_) and is associated with a healthy state (as in young women). However, this pattern is also seen with familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH), in which LDL levels are high77,99 because of overproduction of small VLDL and reduced LDL clearance due to low receptor numbers.76 Finally, formation of small dense LDL is favoured when plasma TG levels exceed 1.7 mmol/L (150 mg/dL),79,80 and especially at levels >2.23 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) due to VLDL overproduction (as in insulin-resistant states, such as Type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome), and potentially when lipolysis is defective due to high apoC-III content [which inhibits lipoprotein lipase (LPL) action and possibly VLDL particle clearance].78,95 An LDL subfraction profile in which small particles predominate (Figure 2C) is part of an atherogenic dyslipidaemia in which remnant lipoproteins are also abundant. As particle size decreases and the conformation of apoB100 is altered, LDL receptor binding affinity is attenuated, resulting in a prolonged residence time in plasma (Box 2).64,78–80

Figure 2.

Model of the metabolic interrelationships between low-density lipoprotein (LDL) subfractions and their hepatic precursors. The liver produces apolipoprotein (apo)B100-containing particles ranging in size from large triglyceride (TG)-rich very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) 1, through small VLDL2 and intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL) to LDL.74 The hepatic TG content (TG pool) affects the profile of the secreted particles.99 Secreted VLDL undergoes lipolysis and remodelling to form remnants/IDL; LDL is then formed via the actions of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), hepatic lipase (HL), and cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP). (A) In people with population average TG levels, about half the lipolytic remnants (which correspond to IDL based on density and size) in this pathway are cleared relatively efficiently and the remainder are converted mainly to LDL-II, which has higher LDL receptor affinity and shorter residence time than the LDL arising from VLDL1.74,79,82,83 The composition of IDL-derived LDL is modulated both by CETP-mediated transfer of cholesteryl esters (CE) from high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and by CETP-mediated transfer of TG from VLDL and their remnants.102,106 (B) In individuals with low plasma TG, LDL-I and -II predominate. Clearance of these lipoproteins is rapid and LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) and apoB concentrations are low. (C) Individuals with elevated plasma TG levels overproduce VLDL1 and have reduced lipolysis rates due in part to inhibition of LPL activity by their abundant content of apoC-III, an LPL inhibitor. Very low-density lipoprotein 1 remodelling gives rise to remnants within the VLDL size range that are enriched in apoE; such circulating remnants can be removed by several mechanisms, primarily in the liver, including the LDL receptor-related protein, heparan sulfate proteoglycans, and LDL receptor.107–109 Hepatic clearance of VLDL1-derived remnant particles may, however, be slowed by enrichment with apoC-III.78 Very low-density lipoprotein 1 and VLDL2 are targeted by CETP, which exchanges core CE in LDL for TG in both VLDL1 and VLDL2. Hydrolysis of TG by HL action then shrinks LDL particles to preferentially form small, dense LDL-III in moderate hypertriglyceridaemia, or even smaller LDL-IV in severe hypertriglyceridaemia; such small dense LDL exhibit attenuated binding affinity for the LDL receptor, resulting in prolonged plasma residence (Box 2). Together, this constellation of lipoprotein changes, originating in increased levels of large VLDL1 and small dense LDL, represents a lipid phenotype designated atherogenic dyslipidaemia,6–8,74,75,79–81,110 a key feature of metabolic syndrome and Type 2 diabetes.6–8,78–80 Typical LDL subfraction patterns are indicated together with relevant plasma lipid and apoB levels. Note that when small dense LDL is abundant, apoB is elevated more than LDL-C. The width of the red arrows reflects the quantity of apoB/particle production and release from the liver, while the width of the blue arrows depicts relative lipolytic efficiency.

Box 2.

The distinct biological features of small dense low-density lipoprotein

- Prolonged plasma residence time reflecting low LDL receptor binding affinity.

- Increased affinity for LDL receptor-independent cell surface binding sites.

- Small particle size favouring enhanced arterial wall penetration.

- Elevated binding affinity for arterial wall proteoglycans favouring enhanced arterial retention.

- Elevated susceptibility of PL and CE components to oxidative modification, with formation of lipid hydroperoxides.

- Elevated susceptibility to glycation.

- Enrichment in electronegative LDL.

- Preferential enrichment in lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2.

- Preferential enrichment in apoC-III.

References: 54,55,64,66,69–75,78,79,81–85,105,111–113

apo, apolipoprotein; CE, cholesteryl ester; PL, phospholipid.

Low-density lipoprotein as the primary driver of atherogenesis

All LDL particles exert atherogenicity to variable degrees, which can be influenced by the proteome, lipidome, proteoglycan binding, aggregability, and oxidative susceptibility.64,96,97 The atherogenic actions of LDL in arterial tissue have multiple origins. Broadly, these encompass:

- Formation of macrophage-derived foam cells upon phagocytic uptake of aggregated LDL particles, or LDL in which lipid and/or protein components have undergone covalent modification, triggering uptake by scavenger receptors. Aggregation may occur by non-enzymatic or enzymatically induced mechanisms. Oxidation of lipids (phospholipids, cholesteryl esters, and cholesterol) or apoB100 can occur enzymatically (e.g. by myeloperoxidase) or non-enzymatically (e.g. by reactive oxygen species liberated by activated endothelial cells or macrophages).

- Release of bioactive proinflammatory lipids (e.g. oxidized phospholipids) or their fragments (e.g. short-chain aldehydes) subsequent to oxidation, which may exert both local and systemic actions.

- Formation of extracellular lipid deposits, notably cholesterol crystals, upon particle denaturation.

- Induction of an innate immune response, involving damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs, notably oxidation-specific epitopes and cholesterol crystals). Damage-associated molecular patterns promote recruitment of immuno-inflammatory cells (monocyte-macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and dendritic cells) leading to local and potentially chronic inflammation that can induce cell death by apoptosis or necrosis, thereby contributing to necrotic core formation.

- Induction of an adaptive immune response subsequent to covalent modification of apoB100 by aldehydes or apoB100 degradation with the activation of antigen-specific T-cell responses and anti-bodies.114–118

Beyond LDL, additional apoB-containing lipoproteins (<70 nm diameter) can exacerbate the atherogenic process; these include Lp(a) (which is composed of apo(a) covalently linked to the apoB of LDL and is a major carrier of proinflammatory oxidized phospholipids) and cholesterol-enriched remnant particles metabolically derived from TGRL.6,7,11,13,26,119 Whereas the classic TG-poor LDL requires modification for efficient uptake by arterial macrophages, remnant particles are taken up by members of the LDL receptor family in their native state.107,120 There is also evidence that LPL-mediated hydrolysis of TG from incoming remnant particles enhances the inflammatory response of arterial macrophages, 121,122 and that the internalization of remnants induces lysosomal engorgement and altered trafficking of lipoprotein cholesterol within the cell, 123 thus inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress and activation of apoptosis disproportionate to the cholesterol cargo delivered.

Low-density lipoprotein subfraction profile affects atherogenicity

Under defined cardiometabolic conditions, a specific LDL subclass may become more prominent as the driver of atherogenesis. Several biological properties of small dense LDL could confer heightened coronary heart disease (CHD) risk (Box 2). Certainly, small dense LDL appears to enter the arterial intima faster than larger LDL.111 However, the significant metabolic inter-relationships of small dense LDL with abnormalities of other atherogenic apoB-containing lipoproteins, particularly increased concentrations of VLDL and remnant lipoproteins, have created challenges in assessing the independent contributions of small dense LDL to CHD.81 Nevertheless, in several recent large prospective cohort studies,98,124,125 and the placebo group of a large statin trial,126 concentrations of small dense LDL but not large LDL predicted incident CHD independent of LDL-C. The heterogenous proteomic and lipidomic profiles of LDL particles may also affect their pathophysiologic activity. For example, small dense LDL is preferentially enriched in apoC-III and glycated apoB relative to larger LDL.85,112 Additionally, the small dense LDL subclass includes an electronegative LDL species associated with endothelial dysfunction.113 Moreover, the unsaturated cholesteryl esters in the lipidome of small dense LDL are markedly susceptible to hydroperoxide formation under oxidative stress.73

Low-density lipoprotein particle profiles may also reflect specific genetic influences on LDL metabolism that concomitantly influence CHD risk.98 A notable example is a common non-coding DNA variant at a locus on chromosome 1p13 that regulates hepatic expression of sortilin, as well as other proteins, 127 and is strongly associated with both LDL-C levels and incident myocardial infarction.128 The major risk allele at this locus is preferentially associated with increased levels of small dense LDL, 127 but the mechanistic basis for this association is unknown.

The residence time of LDL in the circulation may be the critical factor in the relationship between plasma LDL subclass level and atherosclerosis risk, as it determines both exposure of arterial tissue to LDL particles and the potential of LDL to undergo proatherogenic intravascular modifications, such as oxidation. Increased plasma residence time can result from deficiency or dysfunction of LDL receptors, as in FH, or from structural or compositional features of LDL particles that impair their binding affinity for LDL receptors, as for small dense LDL.82,83 Indeed, there is evidence of a lower fractional catabolic rate and longer plasma residence time for small dense LDL than for larger LDL in combined hyperlipidaemia.84

Responses elicited by low-density lipoprotein retained in the artery wall

Retention and subsequent accumulation of LDL in the artery wall triggers a number of events that initiate and propagate lesion development.21,50 Due to the local microenvironment of the subendothelial matrix, LDL particles are susceptible to oxidation by both enzymatic and non-enzymatic mechanisms, which leads to the generation of oxidized LDL (oxLDL) containing several bioactive molecules including oxidized phospholipids.129,130 Oxidized LDL, in turn, initiates a sterile inflammatory response by activating endothelial cells to up-regulate adhesion molecules and chemokines that trigger the recruitment of monocytes—typically inflammatory Ly6Chi monocytes—into the artery wall.131 The importance of oxidized phospholipids in the inflammatory response of the vascular wall has been demonstrated through the transgenic expression of an oxidized phospholipid-neutralizing single-chain antibody, which protected atherosclerosis-prone mice against lesion formation.132 Newly recruited monocytes differentiate into macrophages that can further promote the oxidation of LDL particles, which are then recognized and internalized by specific scavenger receptors giving rise to cholesterol-laden foam cells.133 Several other modifications of retained LDL, including enzymatic degradation or aggregation, have also been shown to promote its uptake by macrophages. Macropinocytosis of native LDL may also contribute to this process.134,135

Macrophages exhibiting different phenotypes, ranging from classical inflammatory subtypes to alternatively activated anti-inflammatory macrophages, have been identified in atherosclerotic lesions.136,137 Macrophage polarization appears to depend on the microenvironment, where different pro- and anti-inflammatory inducers are present together with complex lipids, senescent cells, and hypoxia.137 Thus, macrophage behaviour is a dynamic process adapting to the microenvironment, thereby allowing macrophage subsets to participate in almost every stage of atherosclerosis.138

Several DAMPs, generated by modification of retained LDL, induce the expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic genes in macrophages by engaging pattern recognition receptors, such as toll-like receptors (TLRs). In particular, recognition of oxLDL by a combination of TLR4-TLR6 and the scavenger receptor CD36 triggers NFκB-dependent expression of chemokines, such as CXCL1, resulting in further recruitment of monocytes.139 Such leucocyte recruitment is tightly controlled in a stage-specific manner by a diverse range of chemokines and their receptors.140 At later stages of plaque development, the pool of intimal macrophages is largely maintained by self-renewal, which increases the burden of foam cells in the plaque. Moreover, SMCs may take up cholesterol-rich lipoproteins to become macrophage-like cells that contribute to the number of foam cells in advanced lesions.141

An important consequence of lipid loading of macrophages is the formation of cholesterol crystals, which activate an intracellular complex, the NLRP3 inflammasome, to promote local production of IL-1β and IL-18.142–144 The persistent presence of lipid-derived DAMPs in the artery wall, together with continuous expression of inflammatory cytokines and recruitment of phagocytes (whose role is to remove the triggers of inflammation), sustains this inflammatory response. It also facilitates an active cross-talk with several other arterial cells, including mast cells, which in turn become activated and contribute to plaque progression by releasing specific mediators.145

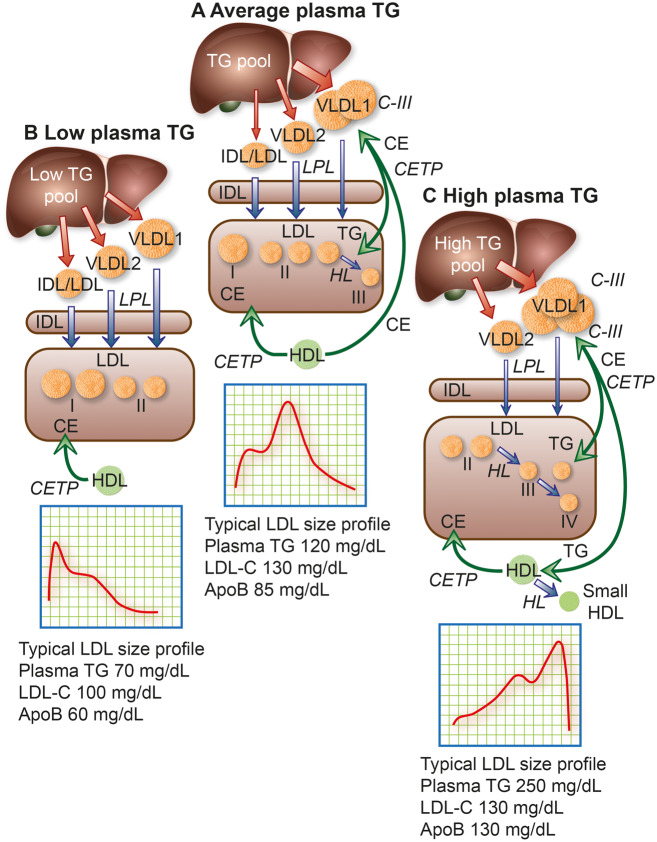

The recruitment of myeloid cells is also accompanied by the infiltration of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that display signs of activation and may interact with other vascular cells presenting molecules for antigen presentation, such as major histocompatibility complex II.146 Analyses of the T-cell receptor repertoire of plaque-infiltrating T cells demonstrated an oligoclonal origin of these T cells and suggest expansion of antigen-specific clones. Indeed, T cells with specificity for apoB-derived epitopes have been identified, linking adaptive immune responses to the vascular retention of LDL (Figure 3).147

Figure 3.

Cellular and humoral immune responses in atherosclerosis. Dendritic cells (DC) take up several forms of modified low-density lipoprotein (LDL), including oxidized LDL (oxLDL), and present specific epitopes (e.g. apolipoprotein B peptides) to naive T cells (Th0), which induces differentiation into CD4+ T helper 1 (Th1), T helper 2 (Th2), T helper 17 (Th17), or T regulatory (T reg) cell subtypes; multiple cytokines control such differentiation. CD4+ T-cell subtypes, together with specific cytokines that they secrete, provide help to B cells and regulate the activity of other T-cell subtypes. The pro-atherogenic role of interferon gamma (IFN-γ)-secreting Th1 cells and the anti-atherogenic effect of interleukin-10/transforming growth factor beta (IL-10/TGF-β)-secreting T regulatory cells are well established. However, the role of Th2 and Th17 in atherogenesis is less clear, as opposing effects of cytokines associated with these respective subtypes have been described. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells can promote atherogenesis. Anti-oxLDL immunoglobulin (Ig)M antibodies produced by B1 cells are atheroprotective, whereas anti-oxLDL IgG antibodies produced by B2-cell subsets are likely pro-atherogenic. All of these cell types may infiltrate the arterial wall at sites of ongoing plaque development, with the possible exception of Th2 and Th17 cell types. EC, endothelial cell; Mph, monocyte-derived macrophage.

Interferon-gamma (IFNγ)-secreting CD4+ Th1 cells promote atherogenesis, but this response is dampened by T regulatory cells expressing transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and IL-10.148 The role of CD4+ Th2 and Th17 cells is less clear, but CD8+ cytotoxic T cells also seem to promote atherogenesis.149 Distinct roles for different B-cell subsets have been reported, and although only small numbers of B cells are found in atherosclerotic lesions, both immunoglobulin (Ig)G and IgM antibodies derived from such cells accumulate.150,151 Many of these antibodies have specificity for oxLDL and, in an isotype-dependent manner, trigger activation of complement, further modulating the inflammatory response.152

Thus, retention and subsequent modification of LDL elicits both innate and adaptive cellular and humoral immune responses that drive inflammation in the artery wall. Disrupting this vicious cycle by targeting inducers and mediators may provide alternative approaches to halting atherogenesis at specific stages (Box 3). Proof of concept for this therapeutic strategy has been provided in a secondary prevention trial in which patients were treated with a statin in combination with the anti-IL-1β antibody canakinumab.154

Box 3.

Cell-specific responses to retained and modified low-density lipoprotein

- Oxidized LDL initiates a sterile inflammatory response by activating endothelial cells to up-regulate adhesion molecules and chemokines, triggering the recruitment of monocytes that differentiate into macrophages.

- Modifications of retained LDL promote its uptake by macrophages leading to cholesterol-laden foam cells.

- Smooth muscle cells also take up cholesterol-rich lipoproteins and significantly contribute to the number of foam cells in advanced lesions.

- Lesional macrophages contain subsets with different phenotypes, ranging from classical inflammatory subtypes to alternatively activated anti-inflammatory macrophages.

- DAMPs, formed when retained LDL become modified, induce the expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic genes in macrophages by engaging PRRs, such as TLRs.

- Lipid loading of macrophages may lead to formation of cholesterol crystals, which activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to production of IL-1β and IL-18.

- T cells and B cells are found in atherosclerotic lesions. The B cells have specificity for oxidized LDL, which also triggers the activation of complement, further modulating the inflammatory response.

References: 129,130,132,133,136–143,145–148,150–153

DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns; IL, interleukin; PRRs, pattern recognition receptors; TLRs, toll-like receptors.

Defective cellular efferocytosis and impaired resolution of inflammation

The efficient clearance of dying cells by phagocytes, termed efferocytosis, is an important homeostatic process that ensures resolution of inflammatory responses (Figure 4).155,156 This involves recognition of several ‘eat-me’ signals, such as phosphatidylserine exposure on apoptotic cells, by their respective receptors on macrophages, as well as bridging molecules that mediate binding. Moreover, ‘don’t-eat-me’ signals, such as CD47, also play a critical role and influence atherogenesis.157 Uptake of apoptotic cells is associated with increased expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokines TGF-β and IL-10 and decreased expression of pro-inflammatory IL-8 and IL-1β by macrophages.158 Efficient efferocytosis thereby protects against atherogenesis by removing cellular debris and creating an anti-inflammatory milieu. Uptake of cellular debris also favours the production of various specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators, such as lipoxins, resolvins, and maresins that are actively involved in resolving inflammation.159

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of processes involved in lesional efferocytosis. (A) Externalized ‘eat me’ signals including phosphatidylserine (PS), calreticulin, and oxidized phospholipids (oxPL) are recognized by their respective receptors, Mer tyrosine kinase (MerTK), low-density lipoprotein-receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1), as well as integrin αvβ3 and CD36 on macrophages; such recognition is facilitated either directly or mediated by bridging molecules such as growth arrest-specific 6 for PS, complement protein C1q for calreticulin and milk fat globule-epidermal growth factor 8 (MFG-E8) for oxPL. Calcium-dependent vesicular trafficking events driven by mitochondrial fission and LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP) promote phagolysosomal fusion and the hydrolytic degradation of apoptotic cells. Simultaneously, natural immunoglobulin (Ig)M antibodies with reactivity towards oxidation-specific epitopes further enhance the efficient clearance of dying cells via complement receptors. (B) In advanced atherosclerosis, one or more of these mechanisms are dysfunctional and can lead to defective efferocytosis, propagating non-resolving inflammation and plaque necrosis. Additional processes contributing to impaired efferocytosis include ADAM-17-mediated cleavage of MerTK as well as the inappropriate expression of the ‘don’t eat me’ signal CD47 on apoptotic cell surfaces. ACs, apoptotic cells.

In chronic inflammation, the general pro-inflammatory environment alters the expression of molecules that regulate efferocytosis, so that oxLDL particles in atherosclerotic lesions compete for uptake by macrophages.129,160 As a result, efferocytosis becomes defective and resolution of inflammation, which is mainly driven by modified LDL, is impaired. Under such conditions, apoptotic cells accumulate and undergo secondary necrosis, promoting the release of several DAMPs that further propagate inflammation. Impaired clearance of apoptotic cells results in the formation of necrotic cores that contribute to unstable plaques and plaque rupture (Box 4). Thus, defective efferocytosis may be a potential therapeutic target to promote resolution of inflammation in atherosclerosis.

Box 4.

Efficient vs. impaired efferocytosis

- Efficient efferocytosis removes cellular debris and modified forms of low-density lipoprotein, and creates an anti-inflammatory milieu.

- Impaired efferocytosis in atherosclerosis results in non-resolving inflammation.

- Impaired clearance of apoptotic cells contributes to formation of necrotic core in atherosclerotic lesions

- Genetically modified mice with enhanced/restored efferocytosis protects from atherosclerosis, indicating novel therapeutic strategies.

How does plaque composition and architecture relate to plaque stability?

Our knowledge of the intricate relationships between plaque stability and the cellular and non-cellular components of plaque tissue, together with their spatial organization, is incomplete. Local SMCs respond to insults exerted by progressive oxLDL accumulation170 by proliferating and ultimately changing their phenotype to fibroblast- and ostechondrogenic-like cells;171 the latter produce extracellular matrix, regulate calcification and contribute (through SMC death) to necrotic core formation. This ‘healing’ response is the major source of key components of advanced plaques but is highly heterogenous. Furthermore, the determinants of this response are diverse, and its interaction with LDL-driven inflammation is poorly understood. Depending on the pathways that predominate in development of a lesion, segments of an atherosclerotic artery may remain quiescent, exhibit chronic stenosis, or precipitate an acute, life-threatening thrombus.

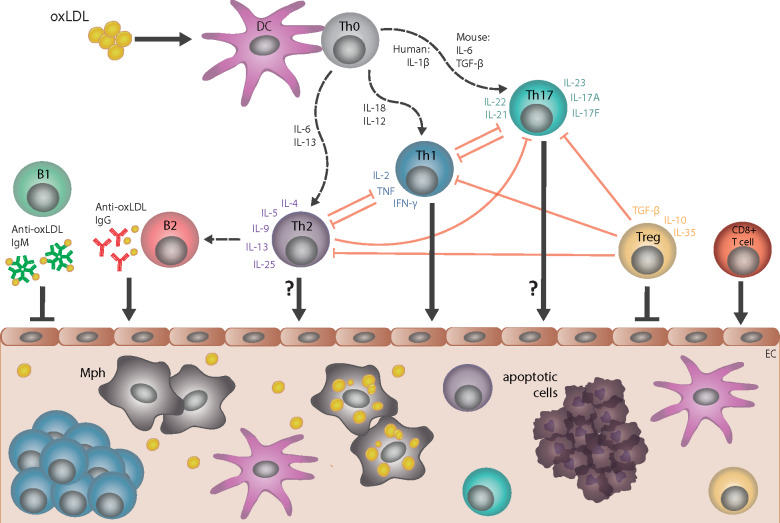

Lesions that develop substantial lipid cores, which almost reach the luminal surface, are at risk of rupturing with subsequent thrombus formation (Figure 5). In this event, the thin cap of fibrous tissue between the lipid core and blood is torn, allowing blood to enter and often core material to leak out. Cholesterol crystals, which can be seen protruding through the plaque surface around sites of rupture, may contribute to final disintegration of the residual cap tissue.172 Ruptured lesions are also typically large with intraplaque angiogenesis and often have little previous stenosis due to extensive expansive remodelling (Box 5).

Figure 5.

Proposed mechanisms of plaque rupture and plaque erosion. Rupture: lesions that develop extensive necrosis and only sparse fibrous cap tissue are at risk of plaque rupture. Suggested final processes that precipitate rupture include senescence and death of residual cap smooth muscle cells (SMC), degradation of the fibrous matrix by macrophage-secreted proteolytic enzymes, and cholesterol crystals, which may penetrate cap tissue. These processes expose the prothrombotic plaque interior and result in neutrophil-accelerated thrombosis. Erosion: lesions that are complicated by erosion typically display variable amounts of plaque necrosis, but are frequently characterized by subendothelial accumulation of proteoglycans and hyaluronan. Current hypotheses suggest that the combination of disturbed blood flow and endothelial activation by immune activators, e.g. hyaluronan fragments, leads to neutrophil recruitment with neutrophil extracellular trapsosis, endothelial cell apoptosis/sloughing, and thrombus formation. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; NETosis, cell death by neutrophil extracellular traps.

Box 5.

Plaque rupture and erosion

- Plaques developing substantial necrosis that reach the luminal surface can rupture and precipitate thrombus.

- Ruptured plaques are often large, non-stenotic, and vascularized lesions with protruding cholesterol crystals, but the causal role of these features is unresolved.

- Thrombus can form on other types of plaques by plaque erosion. The process is less well-understood but may involve combinations of flow disturbance, vasospasm, and neutrophil-generated endothelial shedding.

- Plaque progression and rupture are influenced by both biological and mechanical factors, highlighting plaque composition as a major factor in resistance to mechanical stress.

- Lowering of low-density lipoprotein levels appears more effective in reducing the risk for plaque rupture than for plaque erosion.

Plaque rupture accounts for the majority of coronary thrombi at autopsy (73%), 173 and in survivors of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) examined by optical coherence tomography (∼70%), 174,175 but is less common (∼43–56%) in culprit lesions of non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).175,176 Lesions without lipid cores or with thick fibrous caps are not at risk of rupture but may produce a thrombus in response to plaque erosion. In these cases, the plaque is intact but lacks endothelial cells, and neutrophils predominate at the plaque-thrombus interface. The underlying lesion is frequently, but not always, rich in the glycosaminoglycan hyaluronan and SMCs.173 The mechanism leading to intravascular thrombosis is not yet clear, but experiments with mouse arteries have shown that subendothelial hyaluronan and disturbed blood flow render the endothelium vulnerable to neutrophil-mediated denudation and thrombosis.177 Vasospasm has also been proposed as the initiating event in plaque erosion.178

Rupture requires a specific plaque morphology (thin-cap fibro-atheroma) and is a strong prothrombotic stimulus, whereas erosion complicates earlier lesion types and provides a subtler thrombogenic stimulus. Plaque progression and potentially plaque rupture are influenced by the complex interaction between biological and mechanical factors, indicating that plaque composition is a major factor in its resistance to mechanical stress.179 Erosion favours a higher fraction of thrombi in younger, especially female, patients and in patients with less severe atherosclerosis with few thin-cap fibroatheromas,173,174 and more frequently affects lesions exposed to local (disturbed blood flow near bifurcations) or systemic (smoking) prothrombotic factors.56

Low-density lipoprotein-lowering therapies mitigate key mechanisms of plaque rupture, i.e. lipid core formation and LDL-driven inflammation and degeneration of caps. Statin therapy lowers the rate of events but also shifts the presentation of acute coronary syndromes from STEMI towards NSTEMI, indicating that LDL lowering is less efficient in counteracting erosion mechanisms.176,180 Successful implementation of LDL lowering in patients with established plaques may, therefore, leave a residual burden of thrombosis caused by plaque erosion, thus emphasizing the need for alternative types of prevention and therapy.

Fibrous cap matrix components: guardians of cardiovascular peace?

Lesions that rupture form predominantly in arterial regions with thick pre-existing arterial intima. When the lipid core develops in the deep part of the intima at these sites, it is initially separated from the lumen by normal intima but is gradually replaced by a more compact layer of SMCs and collagen-rich matrix that spreads underneath the endothelium.181 This structure, called the fibrous cap in areas where it overlies lipid core, prevents rupture as long as it is not excessively thin: 95% of ruptured plaques have cap thickness <65 μm (by definition thin-cap fibroatheroma).182 It is uncertain to what extent such thin caps result from degradation of an initially thick cap or from failure to form thick-cap tissue in the first place. From a therapeutic viewpoint, the relationship of LDL-C levels to fibrous cap thickness is of relevance.183 Thus, frequency-driven optical coherence tomography imaging of coronary arteries selected for percutaneous intervention in statin-treated patients with CHD revealed that those with LDL-C levels <1.3 mmol/L (50 mg/dL) were more likely to have fibrous plaque and thick fibrous caps (51.7% and 139.9 μm, respectively).183

Lineage tracking of SMCs showed that fibrous caps in mice form by massive clonal expansion of a few pre-existing SMCs.184,185 These findings are consistent with earlier studies of X chromosome inactivation patterns in human lesions, which indicated the existence of similar large clonal populations in SMC-rich lesion areas.186 If substantial SMC clonal expansion does indeed occur during human cap formation, this may contribute to the replicative senescence and limited repair potential that characterize cap SMCs.187

Several processes leading to cap degradation have been described. Cap collagen and elastin fibres are long-lived with little spontaneous turnover, but invading macrophages, recruited as a result of LDL-driven plaque inflammation, secrete matrix metalloproteinases and cathepsins that break down the matrix.188 Together with SMC and macrophage death, such proteolysis progressively converts cap tissue into lipid core and predisposes it to rupture (Box 6).

Box 6.

Fibrous cap

- The fibrous cap, between the necrotic core and the lumen, protects against rupture.

- Processes integral to both tissue degeneration and reduced cap formation may be involved in the genesis of thin-cap fibroatheromas.

- Caps form by oligoclonal expansion of smooth muscle cells in experimental models, and there is suggestive evidence for the same process in humans.

- Degradation of cap tissue involves inflammatory cell invasion with secretion of proteolytic enzymes. Mechanical effects of local cholesterol crystals may also contribute.

References: 181–191

How does calcification impact plaque architecture and stability?

Arterial calcification is an established marker of atherosclerotic disease,192,193 and the severity of coronary artery calcification is a strong predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.194,195 Yet whether coronary artery calcium (CAC) is simply a marker of advanced disease, or whether it increases risk of plaque rupture, is unclear.

Clinical, animal, and in vitro studies implicate hyperlipidaemia-induced inflammation in the genesis and progression of arterial calcification.196–201 Although statins were expected to prevent and/or reverse vascular calcification, clinical studies showed that, despite benefit on mortality,202 treatment increased progression of coronary artery calcification.203–206 Moreover, elite male endurance athletes have higher CAC scores than less physically active individuals, but experience fewer cardiovascular events.207–209

This paradox raises the question of whether calcified plaque architecture influences rupture vulnerability, either positively or negatively. Understanding in this area, however, remains limited. By using finite element analysis, rigid deposits (calcification) embedded in a distensible material (vessel wall) under tension are shown to create focal stress that is concentrated at areas of compliance mismatch at the surfaces of the deposits, 210 rendering them prone to debonding or rupture. The mineral surfaces found in carotid arteries and those in skeletal bone are remarkably similar and characterized by abundant proteoglycans.211 The chemical nature and architecture of that surface bonding may be critical in determining whether calcium deposits promote plaque rupture or stability.

Clinical studies provide varying results with respect to the association of calcification with plaque rupture. Histological analysis showed that patients who died of acute myocardial infarction had more CAC than controls, but the CAC did not colocalize closely with the unstable plaque.212 Computed tomographic (CT) analyses of patients with acute coronary syndrome, however, showed that the culprit lesions tended to have dispersed or ‘spotty’ calcification (∼0.2–3 mm), whereas stable lesions tended to have contiguous calcium deposits (≥3 mm).213 Based on this and other findings, 214,215 the presence of a spotty pattern of calcium deposits is now considered a feature of a ‘high-risk’ plaque.

A new imaging modality using positron emission tomography (PET)216 detects smaller calcium deposits that are below the resolution of CT (∼200–500 μm)217 and intravascular ultrasound (∼200 μm lateral resolution). In human and animal studies, 18F-NaF PET-CT imaging, which has higher sensitivity for calcium mineral, 218 identified high-risk, vulnerable lesions.218–221

Taken together, these findings suggest that calcification is not a clear marker; mineral features may vary in quality and microarchitecture, which may affect the mechanical properties of plaque tissue.222 For example, certain therapies, such as anabolic parathyroid hormone analogues used to treat osteoporosis, may modify the architecture of calcium deposits and impact calcified plaque vulnerability.219 Research is needed to establish the mechanism linking calcium morphology and plaque vulnerability; the use of 18F-NaF PET scanning offers promise.223 Given the evidence that statins and high-intensity exercise promote calcification without increased risk, these interventions may stabilize mineral morphology. Further studies are needed to better understand these mechanisms in modulating the effects of calcification on plaque vulnerability (Box 7).

Box 7.

Calcification and plaque stability

- Oxidized low-density lipoprotein stimulates vascular calcification by driving osteoblastic differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells.

- High-density lipoprotein exerts beneficial effects on vascular calcification through effects on bone preosteoclasts.

- The severity of coronary artery calcification is a strong predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

- It is still unclear whether coronary artery calcium is simply a marker of advanced disease or whether it increases risk of plaque rupture.

- Clinical studies provide varying results with respect to association of calcification with plaque rupture.

- Statins and high-intensity exercise promote calcification without increasing risk.

References: 192–223

Although the role of LDL in coronary artery calcification remains unclear, 224 it is well-established that an elevated LDL-C level is a strong risk factor for progression of calcification.225 Interestingly, modified LDL stimulates vascular calcification by driving osteoblastic differentiation of vascular SMCs,197 while inhibiting osteoclast differentiation of macrophages.224 In contrast, HDL appears to exert beneficial effects on vascular calcification, as HDL-mediated efflux of cholesterol from bone preosteoclasts inhibits both their maturation and osteoblast RANKL expression, and stimulates their apoptosis.226

In addition, several clinical trials have demonstrated that Lp(a) is an independent risk factor for coronary artery calcification.227 Ongoing research suggests a causal role for Lp(a) in arterial calcification; although the underlying mechanisms remain unclear, oxidized phospholipids in Lp(a) may induce differentiation of valve interstitial cells into a procalcification, osteoblast-like phenotype.228 Ongoing trials with Lp(a)-lowering therapies will provide insight into the potential role of Lp(a) in coronary artery calcification.

Can genes influence the susceptibility of the artery wall to coronary disease?

Genome-wide association studies and related research indicate that predisposition to ASCVD is associated with multiple variants in genes that affect plasma LDL concentration (Figure 6).229,230 Indeed, genomic risk scores that predict coronary artery disease (CAD) risk contain a large number of variants that affect LDL particle quantity and LDL-C levels.231 Most GWAS loci governing LDL-C levels and CAD risk occur in noncoding regions and predominantly alter gene expression that affects uptake and metabolism of LDL in the hepatic cell. Other genomic loci affect qualitative attributes of LDL (Figure 6) including arterial wall susceptibility to LDL infiltration, transcytosis, retention, and modification (Box 8).229

Figure 6.

Genomic loci associated with atherosclerosis. Loci identified by genome-wide association studies (GWAS) can have different effects on low-density lipoprotein (LDL). On the left are shown selected GWAS loci associated with LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) levels, several of which are associated with atherosclerosis events and are incorporated in predictive risk scores. Many have also been independently validated in Mendelian randomization studies and in studies of rare families. Some are proven drug targets to reduce clinical events. On the right are shown loci that do not primarily affect LDL-C levels, but may instead underlie qualitative changes in either the particle itself or in the vessel wall to locally promote atherogenesis.

Box 8.

New concepts in genetic determinants of arterial wall biology and susceptibility to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) reveal causal associations of coronary artery disease with loci for several genes regulating arterial wall susceptibility to infiltration, transcytosis, retention and modification of low-density lipoprotein (LDL).

- The interconnectedness of gene-regulatory networks means that virtually any expressed gene can modulate the function of a ‘core’ disease-related gene.

- Atherosclerosis heritability will ultimately be explained in large part by genes acting outside core mechanistic pathways, as exemplified by non-canonical, LDL-associated genes.

- ‘Omnigenic’ models of disease are being vigorously explored in large-scale GWAS.

A few early GWAS hits for lipid levels and CAD have mechanistic links to LDL transcytosis across the endothelium, including SRB1 encoding SR-B1 and LDLR encoding the LDL receptor.32,232,233 Low-density lipoprotein transcytosis requires caveolin 1,32 encoded by CAV1, in which the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs3807989 is associated with increased CAV1 expression from leucocytes, altered plasma LDL-C levels and increased CAD risk.234

More recent GWAS and sequencing efforts further support a causal role for such qualitative local pathways. For instance, a GWAS of 88 192 CAD cases and 162 544 controls found 25 new SNP-CAD associations from 15 genomic regions, including rs1867624 at PECAM1 (encoding platelet and endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1), rs867186 at PROCR (encoding protein C receptor), and rs2820315 at LMOD1 (encoding SMC-expressed leiomodin 1).235 Another GWAS of 34 541 CAD cases and 261 984 controls from the UK Biobank, with replication in 88 192 cases and 162 544 controls, identified 64 novel CAD risk loci, including several loci implicated by network analysis in arterial wall biology, such as CCM2 encoding cerebral cavernous malformation scaffolding protein and EDN1 encoding endothelin 1.236

Next-generation DNA sequencing of 4831 CAD cases and 115 455 controls identified 15 new CAD loci, which included rs12483885, a common p.Val29Leu polymorphism in ARHGEF26 encoding Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor 26.237 The ARHGEF26 Leu29 isoform had an allele frequency of 0.85 and increased CAD risk by ∼8%, 237 a finding that was confirmed by an independent GWAS in the UK Biobank.238 ARHGEF26 activates Rho guanosine triphosphatase, thereby enhancing formation of endothelial docking structures, and in turn, promoting transendothelial migration of leucocytes.239–241In vitro studies showed the high-risk Leu29 isoform to be degradation-resistant and associated with increased leucocyte transendothelial migration compared with the low-risk Val29 isoform.237_ApoE-_null mice crossed with _Arhgef26_-null mice displayed reduced aortic atherosclerosis without any change in lipid levels,240 supporting a modulatory role for ARHGEF26 in atherogenesis.

Other studies indicate a role for genes governing transcytosis of LDL in CAD. For instance, genome-wide RNA interference screening supplemented by pathway analysis and GWAS data cross-referencing identified ALK1 as a key mediator of LDL uptake into endothelial cells. By directly binding LDL, ALK1 diverts LDL from lysosomal degradation via a unique endocytic pathway and promotes LDL transcytosis.38 Endothelium-specific ablation of Alk1 in _Ldlr_-null mice reduced LDL uptake into cells.38 In studies of highly expressed genes in human carotid endarterectomy samples, lipid metabolism pathways, driven by genes such as ApoE, coincided with known CAD risk-associated SNPs from GWAS.242 Consistent with this mechanism, macrophage-specific re-introduction of apoE in hyperlipidaemic _ApoE_-null mice ameliorated lipid lesion formation independent of LDL levels, indicating a local apoE-related mechanism in the arterial wall.243

Finally, as meta-analyses of GWAS incorporate ever-larger patient cohorts, gene-regulatory networks are recognized as being highly interconnected. For instance, a meta-analysis of GWAS results showed that common CAD-associated variants near COL4A2 encoding collagen type 4 alpha chain, and ITGA1 encoding integrin alpha 9, both of which are important in cell adhesion and matrix biology, were also significant determinants of plasma LDL-C levels.63 For complex traits, such as LDL-C, arterial wall susceptibility, and CAD risk, Boyle et al.244 proposed that gene-regulatory networks are sufficiently interconnected that any gene expressed in disease-relevant cells can modulate the function of core disease-related genes and that most heritability is explained by genes that act outside core mechanistic pathways. This ‘omnigenic model’ of disease is under active investigation in current large-scale genetic studies.

Which plaque components favour a thrombotic reaction upon rupture?

Fibrous cap rupture is defined as a structural defect in the fibrous cap that separates the lipid-rich necrotic core of a plaque from the lumen of the artery.245 The key features of a vulnerable plaque are a thin fibrous cap, a large necrotic core, pronounced inflammation, and low vascular SMC density.246 Both biomechanical and haemodynamic factors contribute to plaque rupture,247 and the exposure of the blood to plaque components initiates the coagulation cascade, promoting thrombus formation at the site of rupture.248 The question is: which plaque components favour this thrombotic reaction?

The initial trigger of thrombus formation is the exposure of tissue factor (TF) in the cell membrane of plaque macrophages and/or lipid-laden vascular SMCs to blood components. Uptake of exogenous non-lipoprotein cholesterol and oxLDL by human monocyte-macrophages and foam cells markedly up-regulates TF synthesis and release of TF+ microvesicles,249,250 with a strong correlation between intracellular cholesterol content and TF production.251,252 Such exogenous cholesterol may be derived from intimally retained atherogenic lipoproteins subsequent to their degradation by macrophage- and SMC-derived foam cells. TF expression may also be induced in endothelial cells by remnant lipoproteins.253 Exposure of the extracellular domain of TF to flowing blood initiates the coagulation cascade,254 and leads to thrombin formation; thrombin then cleaves fibrinogen to fibrin, with ensuing formation of a fibrin monolayer covering the surface of the exposed damaged plaque surface. Thrombosis evolves with a predominance of platelets that are rapidly activated and recruited from the blood to the growing thrombus. In addition, hypercholesterolaemia and oxidized lipids can promote procoagulant activity and propagate the coagulation cascade that is initiated by TF-VIII.249 Moreover, it is established that FH is associated with increased platelet activation and an underlying pro-coagulant state.255 Both native and oxidized forms of LDL may prime platelets and increase platelet activation in response to various agonists, thereby contributing to increased risk of atherothrombosis.256,257 Plasma levels of platelet activation markers (such as thrombin-antithrombin complex, soluble P-selectin, and soluble CD40L) or P-selectin exposure at the surface of platelets can also be enhanced in hypercholesterolaemic patients, and are intimately associated with increased platelet membrane cholesterol.

The healthy endothelium typically exhibits strong anticoagulant, antiplatelet, and fibrinolytic properties that counterbalance prothrombotic factors.258 Upon plaque fissure (or plaque erosion), the local antithrombotic actions of the normal endothelium are lost, as endothelium is absent from the fissured or eroded surface. An important amplifier of the thrombotic reaction upon fissure is the interaction between inflammatory cells and platelets,247 which promotes an autocrine loop stimulating platelet aggregation and adhesion and sustained neutrophil adhesion and recruitment.259 Moreover, both oxLDL and oxidized phospholipids may activate platelets.260 The cardiovascular risk reduction seen with antiplatelet therapy is generally thought to be an effect of platelet inhibition in the event of plaque rupture.261 However, platelets may also have direct involvement in plaque instability.261

Does aggressive low-density lipoprotein lowering positively impact the plaque?

Previous sections in this article have described the complex nature of atherosclerotic plaques, including foam cells, lipid cores, fibrotic caps, necrosis, and calcification, all resulting from the retention and accumulation of LDL in the subendothelial matrix.262 The structural complexity of plaques almost certainly constitutes the basis of the heterogeneous progression of ASCVD from subclinical to clinical, 246,263 as demonstrated in early studies where sites of modest stenosis were observed to rapidly progress to a clinical coronary event upon rupture or erosion of plaques, with subsequent complete occlusion of a vessel.264,265 Recent studies, using a variety of intravascular imaging approaches, show that plaque characteristics can not only predict initial events, but also provide important insights into the course of CHD after an individual’s first episode, lesions with large necrotic cores, and thin fibrous caps being significantly associated with greater risk for subsequent events.266–268

Although the evidence that treatments to reduce LDL-C lead to fewer ASCVD events is unequivocal,4,5 understanding of how the beneficial effects of lower circulating LDL levels translate to changes in the atherosclerotic plaque is less clear. A pioneering investigation of bilateral, biopsied carotid endarterectomy samples at baseline and after 6 months of pravastatin treatment was seminal in demonstrating statin-induced increases in collagen content and reductions in lipid content, inflammatory cells, metalloprotease activity, and cell death, all of which favour plaque stabilization.17 Furthermore, several early studies involving quantitative coronary angiography without269 or with intravascular ultrasound18 demonstrated modest but significant benefits from statin-mediated LDL lowering on the degree of coronary artery stenosis. The magnitude of the effects of statin treatment on plaque volume and composition, particularly the thickness of the fibrous cap and the size of the lipid-rich core have not, however, been uniform among studies, potentially reflecting the differing resolution of the imaging modalities applied and dissimilarities in the underlying substrate.270,271 On the other hand, an open-label study with serial intravascular optical coherence tomographic measurements indicated that efficient LDL lowering can alter the balance between cap formation and degradation, leading to thicker caps and, by inference, lower risk of rupture and thrombosis.272 Of note, reductions in LDL-C by the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab in a secondary prevention trial reduced major coronary events273 and plaque volume274 but did not alter the composition of plaques over 76 weeks of treatment.275 However, the validity of virtual histology for plaque composition measurements remains uncertain.275 Moreover, this trial was conducted in patients previously treated with a statin, suggesting that the lesions studied may, in all probability, have been stabilized to a significant degree before the addition of evolocumab.

Can high-density lipoprotein or its components modulate intra-plaque biology driven by low-density lipoprotein?

Our understanding of the putative direct role of HDL and its major apolipoprotein, apoAI, in the pathophysiology of atherogenesis remains unclear, as does the potential modulation of the atherogenicity of LDL by HDL and its components within plaque tissue (Box 9). Nonetheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that the biological activities of functional HDL/apoAI particles may directly or indirectly attenuate the atherogenic drive of LDL particles in plaque progression.276–281

Box 9.

Apolipoprotein AI (apoAI), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and atherosclerosis

- HDL/apoAI possess diverse functional properties, including cellular cholesterol efflux capacity and anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory activities.

- Which of these activities may be most relevant to intra-plaque biology is unclear.

- HDL/apoAI may slow plaque progression by lipid efflux and by attenuating both intra-plaque oxidative modification of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and inflammatory processes driven by modified LDL. For example, HDL plasmalogens attenuate the propagation of lipid peroxidation in LDL particles.

- Abundant apoAI in human atheroma tissue is typically dysfunctional due to extensive oxidative modification.

The finding of abundant dysfunctional, cross-linked apoAI in human atheroma tissue is perhaps relevant.282 Such dysfunction results from chemical modification (oxidation, carbamylation, or glycation) of key amino acid residues in apoAI by macrophage-derived myeloperoxidase;282 moreover, oxidative modification also alters the endothelial effects of HDL.283,284 These observations raise the possibility that a primary function of apoAI/HDL in plaque tissue is anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative, i.e. apoAI acts to neutralize reactive oxygen species, a central feature of the oxidative stress and inflammation integral to the oxidative modification of LDL and thus to the pathogenesis of accelerated atherosclerosis.285,286 Furthermore, recent data suggest that plasmalogens of the HDL lipidome may also play an antioxidative role by attenuating the propagation of lipid peroxidation in LDL particles.279 These initial insights into the potential actions of HDL/apoAI in counterbalancing the atherogenic effects of LDL particles within plaque tissue require confirmation and extensive additional experimentation.

Missing pieces of the puzzle and their potential translation into innovative therapeutics

Genetic studies suggest that, in addition to LDL, TG-rich remnants and Lp(a) are directly causal in ASCVD, independent of LDL-C levels.6,7,9,11 Indeed, the hazard ratios for myocardial infarction for a 1 mmol/L (39 mg/dL) cholesterol increment were 1.3-fold for LDL, 1.4-fold for remnants, and 1.6-fold for Lp(a) when tested in parallel in approximately 100 000 individuals in the Copenhagen General Population Study (Figure 7).311 Using Mendelian randomization genetic data, the corresponding causal risk ratios for myocardial infarction were 2.1-fold for LDL, 1.7-fold for remnants, and 2.0-fold for Lp(a).

Figure 7.

Comparison of risk of myocardial infarction by 1 mmol/L (39 mg/dL) higher levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, remnant-cholesterol, and lipoprotein(a)-cholesterol from observational and genetic studies. Data from individuals in the Copenhagen General Population Study adapted with permission from Nordestgaard et al.311

These three lipoprotein classes may differ with respect to the mechanisms that underlie their respective contributions to plaque progression (Figure 7 and Box 10). Therefore, combining all three lipoprotein classes as total apoB or non-HDL-C should demand caution. Simplified expressions, such as ‘atherogenic apoB-containing lipoproteins’, may misinform the reader. As described above, LDL-C is a main causal driver of atherosclerosis development and thereby ASCVD, and typically is the most abundant atherogenic particle in the majority of individuals (LDL ∼1 mmol/L; VLDL ∼ 40 µmol/L). Of note, however, HDL particles are some 10-fold more abundant than those of LDL (∼12 mmol/L). Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins or Lp(a) (molar particle concentration range: 0.1–0.7 mmol/L) may be quantitatively more important than LDL in the causation of ASCVD in some individuals as a function of genetic background and metabolic state.

Box 10.

Outstanding questions

- Do the causal mechanisms by which low-density lipoprotein (LDL), lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)], and remnant particles drive atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease differ?

- Do omega-3 fatty acids influence the mechanisms that underlie the atherogenicity of lipoproteins, including remnants and LDL?

- Will therapeutic modulation of apolipoprotein C-III and/or ANGPTL3 attenuate the impact of LDL on arterial plaque biology?

- To what degree can therapeutic modulation of HDL particles and their components attenuate atherobiology driven by LDL?

References: 6,7,9,11,12,287,311–333

ANGPTL3, angiopoietin-like 3.

As a consequence of their elevated cholesterol content (‘remnant cholesterol’, <4000 cholesterol molecules per particle), TG-rich remnants also contribute to intimal cholesterol deposition. Like LDL, remnants enter the arterial intima, in all likelihood by endothelial transcytosis, and are trapped prior to uptake as native (rather than modified) particles by macrophages to produce foam cells.6,312 In addition, hydrolysis of remnant TG by LPL in the arterial intima will produce tissue-toxic free fatty acids and thereby induce inflammation.313,314

In the REDUCE-IT trial, treatment with icosapent ethyl omega-3 fatty acid (4 g daily) resulted in a 25% reduction in ASCVD concomitant with a 20% reduction in plasma TG levels and 40% reduction in C-reactive protein (Box 10).315 This finding is consistent with genetic studies that indicated a causal role of TG in the aetiology of CAD.287,316,317 However, cardiovascular event reduction in the REDUCE-IT trial was independent of TG levels both at baseline and on treatment. This finding might raise questions about the role of TGRL in eliciting clinical benefit. However, consideration of the area under the curve for TGRL and remnants during the atherogenic postprandial period indicates that levels of TGRL and remnants are considerably amplified in subjects with Type 2 diabetes;78 such individuals represented 58% of participants in the REDUCE-IT trial. It is possible that attenuation of the postprandial response by eicosapentanoic acid, the hydrolytic product of icosapent ethyl, may underlie a significant proportion of clinical benefit in the REDUCE-IT trial.

The results of similar cardiovascular outcome trials using another purified omega-3 fatty acid formulation (STRENGTH; NCT02104817) or pemafibrate, a selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha agonist, are eagerly awaited.318 In addition, ongoing phase three trials involving inhibitors of apoC-III319 and of ANGPTL3,320,321 whose action enhances the activity of LPL, should significantly reduce remnant cholesterol and TG levels and may translate into cardiovascular benefit (Box 10).

Implications for future prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

Extensive evidence on the pathophysiology of ASCVD presented here supplements and extends our earlier review on the causality of LDL based on epidemiological, GWAS, and Mendelian randomization studies, as well as controlled intervention trials with pharmacological agents targeting the LDL receptor.4 Such evidence, together with the associated molecular mechanisms, has clear implications across the continuum of ASCVD prevention (i.e. primordial, primary, secondary, and tertiary) and is consistent with the central concept derived from genomics that the cumulative arterial burden of LDL-C drives the development and progression of ASCVD and its clinical sequelae.4,334,335

Furthermore, the pathophysiological evidence supports therapeutic strategies aimed at maintaining very low levels of LDL-C (e.g. <1 mmol/L or 40 mg/dL) in patients with established ASCVD at very high risk of recurrent events.336 Such low plasma LDL-C levels are now attainable with the combination of statins and PCSK9 inhibitors (with or without addition of ezetimibe), therapeutic regimens that have proven safety and tolerability.273,337,338 The unequivocal body of evidence for LDL causality in ASCVD will impact on future international recommendations for the management of atherogenic and ASCVD-promoting dyslipidaemias and will guide the rational use of both existing and new therapies.339–342 The success of modern programmes of ASCVD prevention will also rely on the practice of precision medicine and patient-centred approaches.343

Finally, this thesis has highlighted emerging mechanistic features of atherosclerosis that can potentially lead to evaluation of new therapeutic targets integral to arterial wall biology and plaque stability. Prominent amongst these are endothelial transcytosis of atherogenic lipoproteins, monocyte/macrophage and SMC biology, efferocytosis, inflammation, innate and adaptive immune responses to the intimal retention of apoB-containing lipoproteins and calcification (Take home figure). The future holds great promise but will not be lacking in surprises.

Take home figure.

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and atherobiology. Summary of the principal mechanisms underlying the entry, retention, and accumulation of LDL particles in the artery wall, and subsequent LDL-driven downstream events that are central to the complex pathogenesis of atherothrombosis. Intermediate fatty streak lesions are characterized by subintimal accumulation of macrophage foam cells. AGE, advanced glcation end-products; LDL-C, LDL-cholesterol; MMPs, matrix metallopeptidases

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sherborne Gibbs Ltd for logistical support during meetings of the Consensus Panel, Dr Jane Stock (European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel Administration Office, London, UK) for editorial and administrative support and Dr Rosie Perkins for scientific editing and proof reading.

Funding

The European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) supported travel and accommodation of Panel members and meeting logistics. Funding to pay the open access publication charges for this article was provided by the European Atherosclerosis Society.