laser micromachining (original) (raw)

Acronym: LBMM = laser beam micro-machining

Definition: machining with laser radiation on a micrometer scale

Alternative terms: laser beam micro-machining, laser microfabrication, precision laser machining

Category:  laser material processing

laser material processing

- laser material processing

- laser machining

* laser cutting

* laser drilling

* laser micromachining

* laser micro-drilling, micro-cutting, micro-milling, micro-structuring, micro-patterning, selective laser etching

- laser machining

Related: laser machininglaser material processing

Opposite term: laser macromachining

Page views in 12 months: 1299

DOI: 10.61835/vns Cite the article: BibTex BibLaTex plain textHTML Link to this page! LinkedIn

Content quality and neutrality are maintained according to our editorial policy.

📦 For purchasing laser micromachining, use the RP Photonics Buyer's Guide — an expert-curated directory for finding all relevant suppliers, which also offers advanced purchasing assistance.

Contents

What is Laser Micromachining?

Laser micromachining (also laser beam micro-machining) refers to laser machining of very fine structures, typically on a scale between a few microns and a few hundred microns. The machined parts are not always very small, but at least the structures (e.g. holes, grooves or patterns) made on them. A micrometer-scale precision is required (e.g. for fine-cut contours with low roughness, and small heat-affected zones), thus the related term precision laser machining. However, precision machining is not always part of micromachining.

While the general methods of laser cutting, drilling etc. are described in separate articles, specific technical aspects and applications of micromachining are explained in the following. Typical methods of micromachining are drilling, cutting, milling, marking and structuring; micro-drilling is the clearly dominant application in terms of the number of sold machines.

Note that the term machining is generally applied only to subtractive methods. Therefore, the term laser microprocessing is more general than micromachining, e.g. also including methods of laser additive manufacturing (e.g. with stereolithography) on a micro-scale and micro-joining methods such as micro-welding and soldering. However, subtractive methods dominate, and therefore the term micromachining is much more frequently used than microprocessing.

In comparison to macromachining, laser micromachining faces less competition from other fabrication methods while at the same time some typical limitations such as the relatively high energy input for removing material are less relevant. For these reasons, and because of the steadily growing demand for a great variety of miniature parts, micromachining can be considered a particularly important laser application.

Relevant Properties of Laser Light

Special properties of laser light are particularly relevant in the area of micromachining, namely the possible high spatial coherence, the potential for generating short or even ultrashort pulses, and the high optical intensities reached with such pulses. In fact, the applied intensity levels are often substantially higher than for macroprocessing operations, although the involved average powers are usually smaller. This is because in the micro-domain one works with more tightly focused laser beams and shorter pulses. However, there are also cases where pulse energies of only a few nanojoules are sufficient e.g. for micro-structuring of surfaces.

Laser Sources for Micromachining

Various kinds of laser sources are used for micromachining. Most of those are mentioned in this article; see also the more general article on lasers for material processing.

The ongoing development of laser sources is directed not only at performance (e.g. pulse energy, pulse duration, pulse repetition rate, burst features etc.), but also concerns concepts which allow fabrication of laser systems at lower costs (e.g. in the area of fiber laser technology or microchip lasers) or remove other obstacles to practical applications, such as bulky and too delicate laser machinery. Such developments more and more expand the realistically accessible application areas of laser micromachining. While some laser architectures are still somewhat experimental, an increasing variety of industrial lasers is becoming commercially available. One should not overlook, however, that much of the progress in laser micromachining is based on the development of detailed methods, not just of laser sources.

Resolution Limits of Laser Micromachining

In many cases, the spatial resolution achievable with methods of laser micromachining is essentially limited by the used beam radius — which itself is limited by diffraction in conjunction with the numerical aperture of the focusing optics. Depending on the circumstances, that can lead to a resolution of the order of 1 μm or somewhat better, although in many cases that limit is not fully reached due to various detrimental effects.

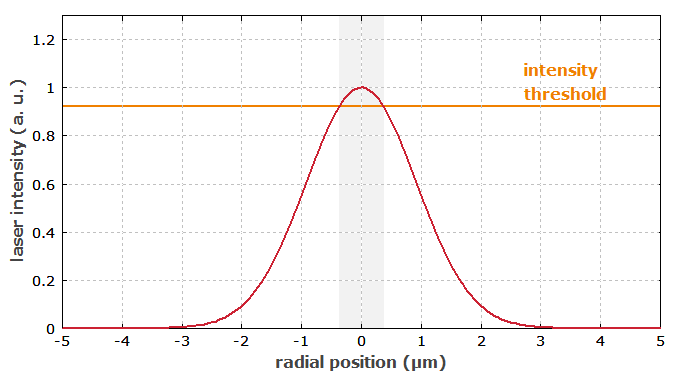

In certain situations, a substantially better resolution is achievable based on physical mechanisms which are explained in the following. At very high optical intensity levels, the interaction of laser light with the material usually occurs via nonlinear processes. For example, nonlinear absorption in a glass or a transparent crystal can be initiated by multiphoton absorption of second, third or even higher order. A substantial interaction often occurs only above a certain threshold level for the optical intensity, which implies that the spatial transition between affected and non-affected parts of the material can be substantially steeper than the laser intensity profile. Therefore, the initiated process may take place only in the inner part of a Gaussian intensity profile; that affected region can be far smaller than the intensity profile (see Figure 1). However, even if the interaction threshold is well-defined and one lowers the pulse energy until only the innermost part reaches that threshold, one cannot make arbitrarily small structures due to fluctuations e.g. of the pulse parameters. In the best cases, features with dimensions well below 100 nm have been achieved.

Figure 1: If the utilized physical mechanism occurs only above a certain intensity threshold, it may be limited to a region (shown in gray) which is much smaller than the diameter of the laser beam.

A more exotic approach is the use of near-field effects, e.g. based on nanotips for local laser field enhancement. While such methods can lead to much improved spatial resolution, they are probably not suitable for widespread industrial applications.

Movement Control and Software

Apart from the laser sources, additional technologies play an important role in laser micromachining. In particular, one requires accurate, fast and reliable devices for motion control; basically always, the machining processes need to be highly automated because manual control is already impossible due to the required precision.

Obviously, the very high potential for ultrafine resolution can be realized only when the motion control devices are sufficiently precise: they need to accurately find given positions in three dimensions with good repeatability and low sensitivity to external effects like vibrations. Feedback systems based on highly precise position measurement devices are usually needed.

For industrial applications as well as for the initial development, micromachining systems need to be properly interfaced with suitable design software. They can be fully integrated into large manufacturing environments.

Laser Micro-drilling

One of the attractions of laser drilling is that it can be performed on a very small scale. Laser beams with high beam quality can be focused such that a small beam radius is obtained in combination with a long enough effective Rayleigh length for drilling holes with a substantial depth.

Drilling in Foils

The easiest task is to drill micro-holes in thin foils, where the beam divergence is not particularly important. Here, holes with the smallest diameters (often only a few micrometers) can be drilled, e.g. for fabricating fine sieves and filters. Usually, one hole is obtained with a single laser pulse, where the pulse duration can be in the nanosecond, picosecond or even femtosecond domain. The pulse repetition rate can easily be in the kilohertz domain, so that thousands of holes can be drilled within a second. The lowest cost from the laser source is possible for nanosecond pulses, where a simple Q-switched laser can be used. However, one can also use nanosecond pulses from excimer lasers because UV light is much better absorbed in many materials. It is usually not necessary to use much shorter pulses for drilling in thin foils.

Drilling in Thicker Layers

For drilling in thicker plates, particularly in metals, small hole diameters imply large aspect ratios, and in that situation the beam divergence becomes relevant. Ideally, one has a diffraction-limited Gaussian beam, where an important parameter is the Rayleigh length: it is the longitudinal distance from the beam focus where the beam area becomes two times larger. For example, for a beam radius of 10 μm of a 1064-nm Gaussian laser beam, the Rayleigh length is 295 μm. That suggests that the depth of a hole with a diameter of the order of 20 μm (twice the beam radius) can reach the order of 0.3 mm, if the hole diameter is supposed to be approximately constant. That estimate, however, is not necessarily accurate because reflection at the hole walls may help to guide the laser light, so that effectively even a substantially larger aspect ratio of the holes is achievable. That depends on the material properties, of course. Also, one should optimize various details of the drilling process. For example, it can be advantageous to employ a beam with azimuthal polarization, which increases reflection at hole walls, thus somewhat supporting the propagation of laser light down the hole. Also, one should optimize the longitudinal focus position.

Best results for holes with large aspect ratios are usually achieved with rather short laser pulses, i.e., using picosecond or even femtosecond lasers. Note, however, that femtosecond pulses are not necessarily better suited than pulses in the low picosecond region, at least in the case of metals. Note that it typically takes at least several picoseconds in metals for the electrons to transfer their energy to the lattice (electron–phonon coupling, electron-lattice thermalization), so that shorter pulse durations cannot provide a substantial advantage in terms of avoiding detrimental effects of heat.

The situation is different for micro-drilling in glass materials because in that case substantial absorption can be achieved only based on nonlinearities (multiphoton absorption followed by avalanche ionization) [21]. Here, femtosecond pulses are advantageous because for the same pulse energy one has a much higher peak power and consequently higher optical intensity at the workpiece. While laser-induced breakdown can also be achieved with nanosecond pulses at lower intensity levels, it then depends on initial carriers generated at randomly distributed material defects. With picosecond or femtosecond pulses, one utilizes a much more deterministic breakdown process, which is correspondingly better in terms of high-quality results on small spatial scales.

Applications of Laser Micro-drilling

Some typical application areas for laser micro-drilling:

- A prominent industrial example is the fabrication of high-pressure fuel injection nozzles, as used mainly for diesel engines. For optimized (steady and complete) combustion of the diesel fuel, it is desirable to generate a very fine spray of the fuel in air by injecting the fuel with very high pressure (nowadays often far more than 1000 bar) through several rather thin and yet stable nozzles. For that, micro-holes (with diameters of less than 150 μm) need to be drilled in stainless steel of substantial thickness, ideally with some conicity — with an increasing hole diameter on the inner side, which, however, is not accessible by tools. With picosecond laser sources, such holes can now be drilled with high quality and at a reasonable cost.

- Much tinier holes are needed for the nozzles of inkjet printers — one of the earliest industrial applications of laser micromachining. A typical inkjet printer has these nozzles in some polymer material such as polyimide, which is relatively easy to process with lasers. To achieve high printing resolution, the hole diameters need to be very small — e.g. 30 μm or even less. At the same time, the hole diameters need to be highly reproducible to obtain consistent high-quality results. Also, the holes should have very clean shapes.

- In microelectronics, microvias are often used; these are interconnects between different layers of electronic circuits. Some of these cross over multiple layers of high-density interconnect (HDI) substrates. Microvias can be made by drilling sub-millimeter holes and filling them with conducting metal. Instead of using tungsten-carbide drills, which are expensive, rapidly wear out or even break, pulsed lasers (e.g. CO2 or Q-switched and frequency-tripled Nd:YAG lasers) are now preferred for drilling at rates of many hundred holes per second. That high throughput and the huge number of holes which can be drilled without maintenance are substantial advantages.

Laser Micro-cutting and Milling

Laser cutting may be used to completely remove certain parts, or to produce tiny slits, grooves or other kinds of microstructures (patterns) of possibly more complicated geometric shapes. Laser milling means ablating material layer by layer.

Laser cutting and milling processes have been optimized for many kinds of metals, including stainless steel, titanium and a wide range of alloys based on copper, aluminum or others. Further, micromachining is done on semiconductor materials (e.g. on the silicon wafers), ceramics, glasses, polymers and composite materials such as fiber-reinforced plastics. Relevant material properties like light absorption and reflection, thermal conductivity, mechanical strength and the tendency for oxidation vary quite a lot. Consequently, a wide range of different lasers is utilized. In most cases, these are pulsed lasers, but they involve very different types such as diode-pumped solid-state lasers (with pulse durations from femtoseconds to nanoseconds), partly frequency-converted e.g. to the green or UV, CO2 lasers and excimer lasers. Particularly for micro-processing, the absorption length typically needs to be quite small, if linear absorption is used, or otherwise strong nonlinear absorption must occur at the applied intensity levels.

In the case of glasses, diamond or sapphire, e.g. for tiny optical windows or precise processing of the edges of larger windows, sufficiently strong absorption of laser light can be achieved by working with ultraviolet lasers (typically with nanosecond pulse durations) or alternatively with ultrafast lasers mostly in the near-infrared. In the latter case, nonlinear absorption processes are utilized.

Some more examples of applications of micro-cutting and milling:

- Micro-machines are developed, for which various very small parts are required, such as turbine rotors and gear wheels. They often feature structure sizes of only a few tens of microns, which are hard to achieve with traditional machining technology. Similarly, miniature parts are required for mechanical watches, sensors and microfluidic devices.

- A particularly prominent example are stents for implantation into arteries, such as those of the heart. These stents need to be fairly elastic structures to be flexibly inserted into arteries. They are produced from thin metal tubes by cutting out substantial parts of the material such that the tubes can be bent much more and connect with the artery tissue. Different materials are used for such stents, often seeking to obtain optimum biocompatibility. While such materials are sometimes particularly difficult to machine with other methods, laser machining can still work well.

- In the production of photovoltaic cells, lasers can be used for various steps in the processing of the silicon wafers. For example, laser ablation and scribing can be applied to silicon or metal layers to obtain the desired structures. Besides, device surfaces can be optimized for light absorption with laser-made nanostructures [27].

- Semiconductors also need to be cut and milled for microelectromechanical systems (MEMS). For example, one sometimes needs tiny cantilevers which can vibrate with very high frequencies. While such microstructures are often fabricated with non-laser methods such as lithography and etching, laser cutting can expand the range of possibilities.

- Micromachining techniques are applied in the manufacturing of liquid crystal displays and other types of digital displays.

- Miniature optical components such as microlenses can be manufactured with laser micromachining. The original milling process can be followed by laser polishing (based on remelting of a surface layer). While there are alternative fabrication methods, for example based on lithography and etching processes, laser-based methods have advantages such as greater flexibility concerning feature details, a lower number of processing steps and overall less expensive machinery (compared with clean room facilities, for example).

- Photonic metamaterials and photonic crystals may be fabricated with different methods, with laser-based methods being one possibility. Where the spatial resolution cannot be better than diffraction-limited, one needs to use a relatively short wavelength of the processing laser compared with the wavelength for which the structures are supposed to function.

- Diffraction gratings have traditionally been made by ruling, i.e., with mechanical tools, or with holographic methods, but they can also be made by laser milling. For example, one can use excimer lasers on polymer substrates, or ultrafast solid-state lasers on glass substrates. Micromachining is also used for other kinds of diffractive optics. In order to achieve a sufficiently high spatial resolution, one may have to use a relatively short laser wavelength compared with the operating wavelength.

- Devices for optical fiber communications require tiny mechanical parts containing features like fiber clamps and mounts for micro-optical components.

- Microstructured ceramics are needed e.g. for sensors or biochips (in biomedical applications). They can be machined with CO2 lasers, excimer lasers and solid-state lasers.

Selective Laser Etching

In contrast to various other methods of laser micromachining, selective laser etching adds a second step: selective chemical etching of the parts of a sample which have previously been irradiated with a laser. In the end, irradiated material is not only modified, but fully removed.

This works well in certain glasses (e.g. fused silica or borosilicate glass) and in sapphire, for example. There a diverse application areas such as micro-fluidics, micro-optics, micro-mechanics and MEMS, micro-electronics, and photonic integrated circuits.

See the article on selective laser etching for details.

Surface Micro-structuring with Lasers

Some applications of laser micromachining involve the structuring of surfaces — often on relatively large parts, but introducing structures on a micrometer scale, hardly visible to the naked eye. Various kinds of laser-based processes have been developed for such purposes.

In some cases, the structures are directly determined by an appropriate application of a tightly focused laser beam, e.g. by applying laser shots in a predetermined pattern. In other cases, some kind of pattern arises from a kind of self-organization process started by the laser radiation but not determined in detail by its properties. For example, irradiation of surfaces (e.g. of silicon, diamond or polymers) with femtosecond laser pulses with a fluence near the ablation threshold can lead to nanoripples (laser–induced periodic surface structures), while nanosecond pulse irradiation has led to ripples with larger periods, apparently generated by the interference of incident and reflected light. Such laser texturing can lead to changes in various surface properties, such as friction, adherence to other bodies, wettability, electrical and thermal conductivity, and light absorption and reflection, which are relevant for a wide range of applications.

Some examples of applications are:

- Surfaces of thin-film photovoltaic cells can be optimized by texturing for minimizing reflection losses, and in other cases surfaces get less prone to deposition of dirt because of the achieved hydrophobic properties. Sometimes, such structuring processes are used as a preparation for further processes, for example the application of a coating.

- Laser honing is applied e.g. to pistons and cylinders in combustion engines to improve their durability and reduce friction. Here, one applies intense pulses of ultraviolet light from an excimer laser (e.g. xenon chloride, 308 nm) to the metal surface. This leads to quite intense surface modifications, but only in a small depth of e.g. 2 μm. The process is done in a nitrogen atmosphere and also involves the incorporation of some nitrogen in the material. A thin robust layer of material with structures on a nanometer scale is formed. During operation in a combustion engine, the lubricant penetrates the created microscopic voids, and those help one to avoid the removal of the lubricant film from the surface.

- Microscopic surface structures are fabricated to make surfaces super-hydrophobic. They are then also less prone to the deposition of dirt.

- In other cases, surface structures improve the wetting properties, for example as a preparation of carbon fiber-reinforced plastics for bonding or gluing with adhesives.

Laser Micro-marking

Laser marking can be based on a variety of principles, such as laser ablation of colored surface layers (exposing the base material, which has a different optical appearance) and other kinds of laser surface modification, e.g. inducing chemical changes at the surface.

In most cases, the involved processing affects only a depth of material far below 1 mm, so that the “micro” aspect applies at least to that longitudinal direction. The transverse resolution needs to be particularly high e.g. when very small letters and digits need to be produced. Because only a quite small depth of material is affected, it is in principle not particularly challenging to achieve a sufficiently small beam diameter for fine marking. Still, a reasonably large Rayleigh length is usually desirable because otherwise the longitudinal focus position would need to be controlled very precisely. Therefore, beam quality can still be an important aspect.

By strongly focusing intense ultrashort laser pulses into regions inside some transparent medium like glass, one can create tiny spots which are visible due to micro-cracks, a modified refractive index or other details. With many such points, visible 3D structures can be written into such materials (see Figure 2). In that case, a small Rayleigh length is desirable to obtain a good resolution also in the longitudinal direction.

Figure 2: Picture of a car, 3D printed into a glass block with laser pulses.

Other Micromachining Operations and Applications

Beyond the classical areas of micro-drilling, cutting and marking, there are some other areas of laser micromachining:

- Laser ablation can be utilized for trimming electrical resistors. Here, tiny parts of a conducting layer are ablated until the desired electrical resistance is achieved. That way, resistors with tight tolerances can be fabricated.

- It is possible to write waveguide structures into certain glasses. Here, a laser beam is tightly focused to some depths inside the glass material, and ultrashort pulses lead to some material modification around the focus which leads to a permanently increased refractive index. It is possible to create 3D structures containing such waveguides; for example, one can map the cores of a multi-core fiber to a linear array of waveguide outputs. One can also realize components like couplers and splitters. Such photonic integrated circuits are of interest in optical fiber communications and for certain instruments in optical metrology based on interferometers, for example. Other uses are for waveguide lasers and optofluidic systems.

- Fiber Bragg gratings can also be written “point by point” with a tightly focused laser beam [23]. In comparison with techniques based on interference patterns from diffraction gratings, one has full flexibility concerning the created refractive index modulation, as there is basically no limitation for the possible length of the fiber Bragg grating except for limitations arising from aspects of accuracy.

For some of those operations, it is debatable whether the term micromachining (which is in principle limited to subtractive processes) is still appropriate.

Frequently Asked Questions

This FAQ section was generated with AI based on the article content and has been reviewed by the article’s author (RP).

What is laser micromachining?

Laser micromachining is a form of laser machining used to create very fine structures, typically on a scale from a few to several hundred micrometers. It involves subtractive processes like drilling, cutting, and milling to achieve high precision on miniature parts or features.

What are typical applications of laser micromachining?

Key applications include drilling high-pressure fuel injection nozzles and inkjet printer heads, creating microvias for electronics, and manufacturing medical stents. It is also used for processing photovoltaic cells and fabricating micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS).

Why are ultrashort pulse lasers often used for micromachining?

Ultrashort pulses from picosecond lasers or femtosecond lasers minimize detrimental heat effects, leading to very high-quality results with minimal heat-affected zones. For transparent materials like glass, they enable precise material removal through nonlinear absorption.

Can laser micromachining create structures smaller than the laser spot size?

Yes, by utilizing nonlinear processes that occur only above a certain optical intensity threshold. The material is modified only in the central part of the focused laser beam where intensity is highest, allowing the creation of features significantly smaller than the beam's diameter.

What is the difference between laser micromachining and laser microprocessing?

Laser micromachining refers specifically to subtractive methods like drilling and cutting where material is removed. Laser microprocessing is a broader term that also includes non-subtractive methods such as micro-laser welding or laser additive manufacturing on a micro-scale.

What is laser surface micro-structuring?

Laser surface micro-structuring is the creation of micrometer-scale patterns on a material's surface. These structures can alter physical properties like wettability, friction, or light absorption for applications like optimizing solar cells or improving lubricant retention.

Which types of lasers are used for micromachining?

A wide range of lasers are used, including diode-pumped solid-state lasers (from nanosecond to femtosecond pulses), excimer lasers for UV light, and CO2 lasers. Nonlinear frequency conversion is often used to generate green or UV light for better material absorption.

Suppliers

Sponsored content: The RP Photonics Buyer's Guide contains 23 suppliers for laser micromachining. Among them:

⚙ hardware🧩 accessories and parts💡 consulting🧰 development

Femtika develops and produces both standardized and custom femtosecond laser machines for industrial and scientific applications:

- Glass Laser Workstation — a standardized, user-friendly system designed to make glass micro-processing more accessible for research and manufacturing

- FBG Writing Workstation — a dedicated setup for Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) inscription, with options for automation in industrial production environments

- R&D Laser Workstation — a fully customizable solution that can integrate Selective Laser Etching (SLE), Multiphoton Polymerization (MPP), and other femtosecond laser processes in a hybrid configuration, supporting complex microfabrication in a single system

For prototyping and production, Femtika offers contract manufacturing services, delivering microfabricated components without the need for in-house equipment.

⚙ hardware

Thorlabs designs and manufacturers a suite of 1-axis and 2-axis scanning galvanometer mirrors for micromachining, laser marking, imaging, and beam steering applications. Our BLINK high-speed focuser can be used with XY scanning systems to provide Z-axis focal correction. For an all-in-one XYZ scanning system, consider our 3-axis galvo scan heads, which integrate dynamic Z-axis focusing with XY galvos in a compact design.

⚙ hardware

WOP offers ultra-high precision femtosecond laser micromachining workstations for industry and science needs. We design and manufacture tailor-made laser systems for your custom laser micromachining applications:

- FemtoLAB — all-in-one R & D platform for laser micromachining. Perfect choice -for universities and R & D centers

- FemtoGLASS — glass and sapphire laser cutting and dicing workstation ideal for research and development, and volume manufacturing.

- FemtoFBG — laser micromachining workstation optimized for Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) writing

- FemtoMPP — laser micromachining workstation optimized for multiphoton polymerization (MPP) technology

- FemtoFAB — highly reliable, ultra-high precision industrial laser micromachining workstation

Bibliography

| [1] | P. P. Pronko et al., “Machining of submicron holes using a femtosecond laser at 800 nm”, Opt. Commun. 114, 106 (1995); doi:10.1016/0030-4018(94)00585-I |

|---|---|

| [2] | B. C. Stuart et al., “Nanosecond-to-femtosecond laser-induced breakdown in dielectrics”, Phys. Rev. B 53, 1749 (1996); doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.53.1749 |

| [3] | K. M. Davis et al., “Writing waveguides in glass with a femtosecond laser”, Opt. Lett. 21 (21), 1729 (1996); doi:10.1364/OL.21.001729 |

| [4] | K. Miura et al., “Photowritten optical waveguides in various glasses with ultrashort pulse laser”, Appl. Phys. Lett. 71, 3329 (1997); doi:10.1063/1.120327 |

| [5] | X. Liu, D. Du and G. Mourou, “Laser ablation and micromachining with ultrashort laser pulses”, IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quant. Electron. 33 (10), 1706 (1997); doi:10.1109/3.631270 |

| [6] | M. C. Gower, “Industrial applications of laser micromachining”, Opt. Express 7 (2), 56 (2000); doi:10.1364/OE.7.000056 |

| [7] | C. B. Schaffer et al., “Micromachining bulk glass by use of femtosecond laser pulses with nanojoule energy”, Opt. Lett. 26 (2), 93 (2001); doi:10.1364/OL.26.000093 |

| [8] | A. Marcinkevicius et al., “Femtosecond laser-assisted three-dimensional microfabrication in silica”, Opt. Lett. 26 (5), 277 (2001); doi:10.1364/OL.26.000277 |

| [9] | K. Minoshima et al., “Photonic device fabrication in glass by use of nonlinear materials processing with a femtosecond laser oscillator”, Opt. Lett. 26 (19), 1516 (2001); doi:10.1364/OL.26.001516 |

| [10] | C. B. Schaffer, A. Brodeur and E. Mazur, “Laser-induced breakdown and damage in bulk transparent materials induced by tightly-focused femtosecond laser pulses”, Meas. Sci. Technol. 12 (11), 1784 (2001) |

| [11] | A. M. Streltsov and N. F. Borrelli, “Study of femtosecond-laser-written waveguides in glasses”, J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 19 (10), 2496 (2002); doi:10.1364/JOSAB.19.002496 |

| [12] | M. Will et al., “Optical properties of waveguides fabricated in fused silica by femtosecond laser pulses”, Appl. Opt. 41 (21), 4360 (2002); doi:10.1364/AO.41.004360 |

| [13] | A. P. Joglekar et al., “A study of the deterministic character of optical damage by femtosecond laser pulses and applications to nanomachining”, Appl. Phys. B 77, 25 (2003); doi:10.1007/s00340-003-1246-z |

| [14] | S. Nolte et al., “Femtosecond waveguide writing: A new avenue to three-dimensional integrated optics”, Appl. Phys. A 77, 109 (2003); doi:10.1007/s00339-003-2088-6 |

| [15] | A. Chimmalgi et al., “Femtosecond laser apertureless near-field nanomachining of metals assisted by scanning probe microscopy”, Appl. Phys. Lett. 82 (8), 1146 (2003); doi:10.1063/1.1555693 |

| [16] | C. Florea and K. A. Winick, “Fabrication and characterization of photonic devices directly written in glass using femtosecond laser pulses”, J. Lightwave Technol. 21 (1), 246 (2003); doi:10.1109/JLT.2003.808678 |

| [17] | K. Naessens et al., “Direct writing of microlenses in polycarbonate with excimer laser ablation”, Appl. Opt. 42 (31), 6349 (2003); doi:10.1364/AO.42.006349 |

| [18] | A. Zoubir et al., “Practical uses of femtosecond laser micro-materials processing”, Appl. Phys. A 77, 311 (2003); doi:10.1007/s00339-003-2121-9 |

| [19] | M. Sakakura and M. Terazima, “Initial temporal and spatial changes of the refractive index induced by focused femtosecond pulsed laser irradiation inside a glass”, Phys. Rev. B 71, 024113 (2005); doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.71.024113 |

| [20] | A. M. Kowalevicz et al., “Three-dimensional photonic devices fabricated in glass by use of a femtosecond laser oscillator”, Opt. Lett. 30 (9), 1060 (2005); doi:10.1364/OL.30.001060 |

| [21] | R. R. Gattass and E. Mazur, “Femtosecond laser micromachining in transparent materials”, Nature Photonics 2, 219 (2008); doi:10.1038/nphoton.2008.48 |

| [22] | E. Wikszak et al., “Erbium fiber laser based on intracore femtosecond-written fiber Bragg grating”, Opt. Lett. 31 (16), 2390 (2006); doi:10.1364/OL.31.002390 |

| [23] | G. D. Marshall et al., “Point-by-point written fiber-Bragg gratings and their application in complex grating designs”, Opt. Express 18 (19), 19844 (2010); doi:10.1364/OE.18.019844 |

| [24] | K. M. Tanvir Ahmmed, C. Grambow and A.-M. Kietzig, “Fabrication of micro/nano structures on metals by femtosecond laser micromachining”, Micromachines 2014, 5(4), 1219 (2014); doi:10.3390/mi5041219 |

| [25] | K. Sugioka and Y. Cheng, “Ultrafast lasers — reliable tools for advanced materials processing”, Light: Science & Applications 3, e149 (2014); doi:10.1038/lsa.2014.30 |

| [26] | D. S. Correa et al., “Ultrafast laser pulses for structuring materials at micro/nano scale: from waveguides to superhydrophobic surfaces”, Photonics 4 (1), 8 (2017); doi:10.3390/photonics4010008 |

| [27] | A. P. Amalathas and M. M. Alkaisi, “Nanostructures for light trapping in thin film solar cells” (a review), Micromachines 2019, 10, 619 (2019); doi:10.3390/mi10090619 |

(Suggest additional literature!)

Questions and Comments from Users

Here you can submit questions and comments. As far as they get accepted by the author, they will appear above this paragraph together with the author’s answer. The author will decide on acceptance based on certain criteria. Essentially, the issue must be of sufficiently broad interest.

Please do not enter personal data here. (See also our privacy declaration.) If you wish to receive personal feedback or consultancy from the author, please contact him, e.g. via e-mail.

By submitting the information, you give your consent to the potential publication of your inputs on our website according to our rules. (If you later retract your consent, we will delete those inputs.) As your inputs are first reviewed by the author, they may be published with some delay.