Fusobacterium nucleatum — symbiont, opportunist and oncobacterium (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2019 Sep 1.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019 Mar;17(3):156–166. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0129-6

Abstract

Fusobacterium nucleatum has long been found to cause opportunistic infections and has recently been implicated in colorectal cancer; however, it is a common member of the oral microbiota and can have a symbiotic relationship with its hosts. To address this dissonance, we explore the diversity and niches of fusobacteria and reconsider historic fusobacterial taxonomy in the context of current technology. We also undertake a critical reappraisal of fusobacteria with a focus on F. nucleatum as a mutualist, infectious agent and oncogenic microorganism. In this Review, we delve into recent insights and future directions for fusobacterial research, including the current genetic toolkit, our evolving understanding of its mechanistic role in promoting colorectal cancer and the challenges of developing diagnostics and therapeutics for F. nucleatum.

Omics technologies are providing new perspectives on what constitutes a pathogen, as well as the host and microbial features that contribute to pathogenesis, including for disease processes that are not classically regarded as infectious. Interest in microbiome science has led to the microbial sequence-based profiling of an unprecedented number of sample types and tissues and the identification of microbial signals in sites that previously were not considered to harbour microbial communities, although the reliability and relevance of these signals are not always clear. One bacterium that has garnered such attention recently in colorectal cancer microbiome studies is Fusobacterium nucleatum.

Fusobacteria are Gram-negative anaerobic bacilli with species-specific reservoirs in the human mouth, gastrointestinal tract and elsewhere. An association between the presence of F. nucleatum and human colorectal cancer has emerged across both patient populations and disease stages. F. nucleatum has long been considered as an opportunistic pathogen given its frequent isolation and identification in anaerobic samples from patients with different infections. Although well known to the oral and medical microbiologist, the role of F. nucleatum as a cancer-causing member of the microbiota is still emerging and is revealing the multi-faceted ways in which a bacterium can contribute to the development, growth, spread of and treatment response to cancer. Herein, we undertake a critical reappraisal of fusobacteria with a focus on F. nucleatum as a mutualist, infectious agent and oncobacterium.

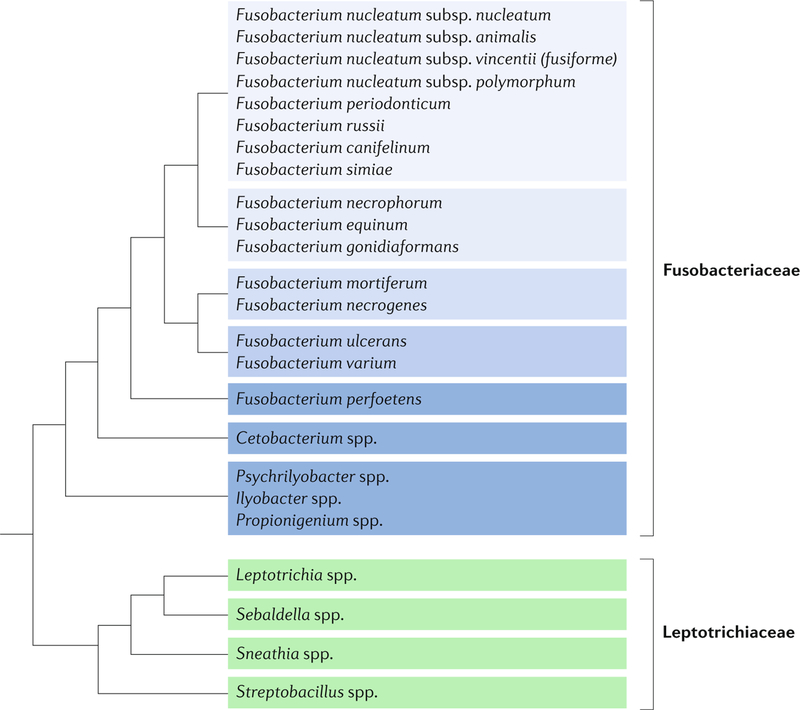

Fusobacterial diversity and niches

Despite the diversity of bacterial life, much of microbiological research has focused for a long time on certain lineages, such as Proteobacteria, on the basis of their importance to human health and agriculture, novelty in metabolic capability and, to an extent, ease of study (for example, because of culturability and genetic tractability). Increasingly, omics data are demonstrating that our current focus within the microbial world is limited given the diversity of unexamined microorganisms1,2 and the potential roles of less-studied micro-organisms in human disease and the environment. Fusobacteria, a distinct phylum of bacteria, are a prime example of previously understudied taxa. This phylum includes species commonly found in the human oral cavity (Fusobacterium spp.), human intestinal and urogenital tracts (Leptotrichia spp. and Sneathia spp., respectively), the intestinal tracts of fishes and whales (Cetobacterium spp.) and free-living in the marine environment (Ilyobacter spp.). Currently, the Fusobacteria are divided into two families: the Leptotrichiaceae, which include the Leptotrichia, Sneathia, Sebaldella and Streptobacillus genera, and the Fusobacteriaceae, including the marine and aquatic genera Psychrilyobacter, Ilyobacter, Propionigenium and Cetobacterium and the animal-associated Fusobacterium genus we highlight in this Review (Box 1). These understudied bacteria are Gram-negative, non-spore-forming, usually non-motile anaerobes that assume a tapered rod shape, and they can harbour unique metabolic capabilities, such as Psychrilyobacter atlanticus, which has been shown to break down nitramine explosives3.

Box 1 | rethinking history and taxonomy of fusobacteria in the sequencing era.

Beginning in the 1880s and 1890s, scientists noted fusiform rods in various zoonotic and human samples, including both healthy and diseased oral cavities. in the pre-sequencing era, Fusobacterium spp. were defined by their shape and their fermentation of amino acids and glucose to butyrate. On the basis of these criteria, one historic so-called Fusobacterium species frequently isolated from human faecal samples is now known as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. By DNa analyses, F. prausnitzii is genetically more closely related to the Clostridiaceae93. since this realization, Fusobacterium spp. have not been considered to be quantitatively substantial members of the human faecal microbiota. such misclassifications have also occurred for the oral bacteria now known as Eubacterium sulci and Filifactor alocis94. although not unique to fusobacteria, such misnomers highlight the heterogeneity of Fusobacterium spp. that lack conventional, characteristic phenotypes and can complicate delving into the historical literature record.

Genomic analyses have led to greater clarification not just between Fusobacteria and other phyla but also have improved the understanding of differences within Fusobacterium spp.9,78,95 (see the figure; adapted with permission from ref.96, elsevier). Phenotypically, the features that differentiate Fusobacterium nucleatum from other Fusobacterium spp. are largely metabolic and related to fermentation and secreted organic acid profiles, indole and hydrogen sulfide production and bile sensitivity, although these metrics have proved similarly ineffective in differentiating among Fusobacterium spp. as they have in distinguishing fusobacterial species from other phyla. Comparative genomics research suggests an adaptive radiation among these species resulting in three lineages9,96. in this model, F. nucleatum evolved as a lineage with Fusobacterium periodonticum, and these species share not just a niche but also similar functions that are associated with invasion of host cells. F. nucleatum itself can be further delineated into four subspecies97 — nucleatum, animalis, vincentii (inclusive of fusiforme) and polymorphum — although it has been argued that these subspecies are sufficiently divergent at a DNa level as to be considered separate species9,98. traditional consideration of these subspecies as largely either commensal (polymorphum and vincentii) or disease-associated (nucleatum and animalis) merits re-evaluation as fusobacterial isolates from colorectal tumours encompass all of these subspecies45 (Supplementary table 1).

Fusobacterium species are found in the mouth and other mucosal sites of humans and other animals, including mice (Fusobacterium mortiferum), macaques (Fusobacterium simiae), horses (Fusobacterium equinum) and even crocodile lizards (Fusobacterium spp.). Their presence in these healthy tissues suggests that they are natural constituents of the microbiota at these sites. However, as they have been frequently isolated from these same and other tissues in clinical samples during active disease, they are regarded as opportunistic pathogens. Of those species that colonize humans, F. nucleatum is the most abundant in the oral cavity and has come to the forefront of scientific interest in the past decade because of an increasing number of associations with extraoral diseases.

F. nucleatum as a mutualist

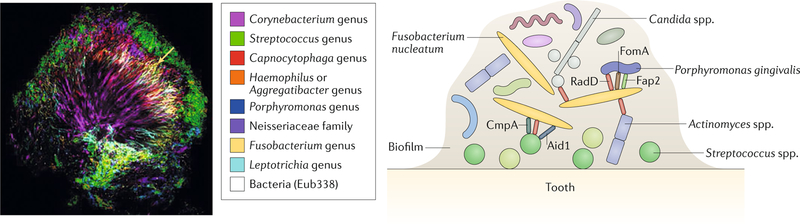

F. nucleatum has evolved in close association not just with the mammalian cells and tissues found in the oral cavity but also with the oral microbiota. F. nucleatum plays integral and beneficial roles in biofilms that contribute to both periodontal health and disease. In a dental plaque biofilm_, F. nucleatum_ serves a structurally supportive role as a bridge organism, connecting primary colonizers such as Streptococcus species to the largely anaerobic secondary colonizers to which it can also bind, including Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans4 (fig. 1). With its elongated shape, F. nucleatum can interact with many other microbial cells. When co-cultured with Streptococcus sanguinis, F. nucleatum and S. sanguinis can assemble into highly ordered corncob-like structures, in which upwards of ten S. sanguinis cells can be bound to a single F. nucleatum cell5. Thus, the long rod shape of F. nucleatum is pivotal in facilitating structural relationships that are key for polymicrobial biofilms and interactions between microorganisms.

Fig. 1. The organizing role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in oral biofilms.

In oral biofilms (left panel, as visualized by combinatorial labelling and spectral imaging–fluorescence in situ hybridization (CLASI-FISH); right panel, schematic to demonstrate specific interactions), Fusobacterium nucleatum functions as a bridging organism that adheres first to early colonizers of the dental surface such as Streptococcus spp. One mechanism for this interaction is the binding of the RadD adhesin of F. nucleatum to the streptococcal adhesin SpaP6. Two other fusobacterial adhesins, Aid1 and CmpA, have also been implicated in this interaction121,122. Once adhered to the developing biofilm, F. nucleatum aggregates with the secondary colonizers such as P. gingivalis using the fusobacterial adhesins RadD, Fap2 and FomA68,123–125. RadD mediates additional interactions between F. nucleatum and Actinomyces naeslundii7 and between F. nucleatum and the fungus Candida albicans8. Left panel reproduced with permission from ref.14, PNAS.

F. nucleatum also mediates important biofilm-organizing behaviour and interactions with host cells through the expression of numerous adhesins (fig. 1). The best characterized fusobacterial adhesin is RadD, which can bind the Streptococcus mutans adhesin SpaP to mediate the co-aggregation of these two bacteria and advanced biofilm organization6,7. The role of RadD in fusobacterial adhesion is multifaceted — it mediates binding not only to bacteria but also to the yeast Candida albicans, which is also part of the oral microbiota8. Invasive Fusobacterium spp., including F. nucleatum, encode several membrane occupation and recognition nexus (MORN) repeat-containing proteins. Although an average of 30 copies of these domains can be found per F. nucleatum genome, their functional roles remain unclear9,10. How this expanded class of proteins may influence the interactions of fusobacteria with other microorganisms and host cells is of great interest; however, their redundancy may also complicate dissection of their individual roles.

Microbial cells within biofilms engage not only in physical interactions but also in cross-feeding and metabolic interactions. Dissecting this chemical crosstalk in the complex communities of an in vivo biofilm is difficult, and simplified in vitro co-culture experiments are providing clarity on how microorganisms communicate with each other. Whereas such metabolic mutualism has been well described for other oral microorganisms, such as P. gingivalis and Treponema denticola11, research on F. nucleatum and its partners is more limited. The most mechanistically developed example of cross-feeding is the ArcD-dependent excretion of ornithine by Streptococcus gordonii, which is then used by F. nucleatum, at least in culture12. Broader metaproteomic analyses have also suggested that metabolic pathways in F. nucleatum, including amino acid fermentation and glycolysis, may be influenced by other microorganisms in a species-specific manner13. Parsing the metabolic languages used among the micro-organisms in the mutualistic oral biofilms remains an exciting area of inquiry. Recent work using the multiplex visualization method combinatorial labelling and spectral imaging–fluorescence in situ hybridization (CLASI-FISH) has suggested that the biogeography of plaque biofilms, and the role of F. nucleatum therein, may be more complex than previously thought, both in structure and in variations across plaque location14. Despite half a century of study on F. nucleatum and oral biofilms, current technologies are raising questions about whether we even know which microorganisms are in direct dialogue with F. nucleatum in its mutualistic niche.

F. nucleatum as an infectious agent

Whereas F. nucleatum has a mutualistic relationship with the other members of the oral microbiota, its interactions with human tissues — whether oral or extraoral — span from neutral to pathogenic in nature. Although the oral biofilms it helps coordinate are found on tooth surfaces in healthy individuals, F. nucleatum is also important in periodontitis as it directly shapes host responses and increases the infectivity of other pathogens. Specifically, F. nucleatum can induce expression of the antimicrobial peptide β-defensin 2 and pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and IL-8, in the oral epithelium15–17. Such _F. nucleatum_-driven inflammation contributes to disease progression in a model of oral tumorigenesis18. In these pathogenic settings, F. nucleatum influences the function of immune cells, such as myeloid cells, in which it activates NF-κB, resulting in TNF production19. As periodontitis is a polymicrobial disease, unravelling how F. nucleatum interacts with other oral microorganisms to drive disease is of utmost importance. Co-infection of macrophages by both F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis blunts inflammasome activation compared with infection with F. nucleatum alone20. Beyond modulating these host responses, F. nucleatum also increases the invasive potential of P. gingivalis21,22, suggesting that these bacteria act cooperatively to evade destruction by the immune system and to develop an inflammatory-permissive environment during periodontitis.

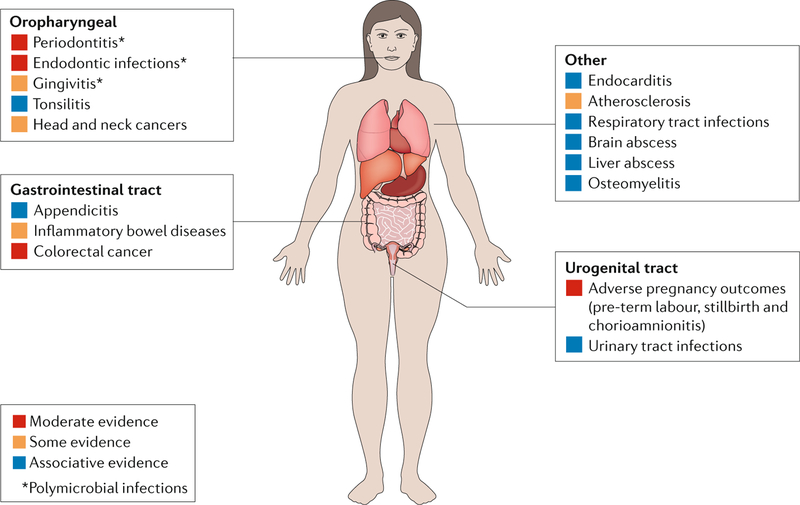

The contribution of F. nucleatum to extraoral diseases remains rather mechanistically speculative. Although F. nucleatum has been isolated from clinical specimens in a variety of diseases, including appendicitis23, brain abscesses24, osteomyelitis25, pericarditis26 and adverse pregnancy outcomes such as chorioamnionitis27 (fig. 2), the role of F. nucleatum in these pathologies remains unclear. Some have suggested that F. nucleatum is a passenger in these disease states rather than a disease driver28. However, F. nucleatum can promote inflammatory responses, as discussed in periodontitis, and can bind and/or invade diverse cell types, including oral, colonic and placental epithelial cells29–31, T cells32, keratinocytes33 and macrophages34, among others. Taken together, these observations suggest that F. nucleatum may have a causative role in several infections, but they do not provide evidence to confirm Koch’s postulates.

Fig. 2. oral and extraoral diseases associated with Fusobacterium nucleatum.

Fusobacterium nucleatum is one of the most commonly isolated oral bacteria in clinical infections, whether found alone or in polymicrobial infections (indicated by an asterisk)126. Unlike the related Fusobacterium necrophorum, for which a causative role in Lemierre syndrome is well established127, whether F. nucleatum functionally contributes to each of these various diseases remains to be determined. We have scored the evidence linking F. nucleatum to the listed infections using a subjective assessment of both the breadth and depth of the existing literature with regard to isolation, association and experimental data in preclinical models. Beyond the oral cavity, there is the most mechanistic support for a role of F. nucleatum in adverse pregnancy outcomes and colorectal cancer. Further, the route of infection, oral or haematogenous, by which F. nucleatum may disseminate to these disparate sites remains to be clarified.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as placental infections and pre-term birth, are the extraoral diseases with the most data supporting a role for F. nucleatum as a driver or causative agent of disease. F. nucleatum is the most common organism isolated from amniotic fluid in pre-term births and can invade the relevant cell type — human umbilical endothelial cells35. Furthermore, preclinical studies that used mouse models have demonstrated that F. nucleatum can localize to the placenta and induce stillbirths in mice when given intravenously35. A specific F. nucleatum adhesin, FadA, has been implicated in these functions30,36,37. Given these observations, F. nucleatum appears to be a bona fide placental pathogen; however, Fusobacterium spp. may also be part of the healthy placental microbiota38. The detection of Fusobacterium spp. in healthy tissues raises the question of whether the frequency with which F. nucleatum is isolated from diseased placentae and amniotic fluid is due, in part, to sampling bias, as pathological tissues are more frequently examined than healthy placentae. Therefore, as in the oral cavity, F. nucleatum may prove to be pathogenic in the placenta only under certain conditions or by specific strains.

F. nucleatum and cancer

Omics and epidemiological associations.

The concept of a microbial role in cancer is not novel — bacteria, parasites and viruses are all associated with potentiating cancer. Human papillomavirus drives mutational changes that lead to cervical cancer and the cag pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori shapes a tumour-permissive microenvironment in the gastric mucosa39. Further, microbial ‘harbingers’ of cancer have historically been used to trigger diagnostic evaluations, such as the presence of Streptococcus gallolyticus bacteraemias for colorectal cancer. The omics explosion has expanded these insights by providing information about the microbial signatures of different cancerous and pre-cancerous tissues. In efforts to define the genomic and transcriptomic profiles of colorectal cancer tissues, investigators have found themselves with an unanticipated bounty of microbial information. Using different computational approaches, two studies in 2012 were the first to observe fusobacterial DNA40 or RNA41 among the vastly more abundant human nucleic acids. Further, the fusobacterial signal was specifically enriched in the tumour tissues relative to adjacent normal tissues, and deeper analysis revealed these sequences to be F. nucleatum. These observations were surprising, although F. nucleatum has been isolated from gastrointestinal infections including appendicitis23 and has also recently been associated with inflammatory bowel disease29,42,43, suggesting a role in gastrointestinal pathologies.

That F. nucleatum nucleic acids are present in colorectal cancer tissues has since been confirmed in several different studies using varied molecular approaches (16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene amplicon sequencing, DNA sequencing (DNA-seq), RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and directed quantitative PCR (qPCR)) and with fluorescent in situ hybridization. Such imaging-based data of bowel tumours suggest that F. nucleatum is in intimate association with the colorectal crypts44 and is perhaps even intracellular40. Further, and very importantly, that viable F. nucleatum is present in these tissues has been verified by isolating F. nucleatum strains directly from biopsy samples41,45 and from patient-derived xenografts passaged in mice46. Many independent studies have since observed this association in biopsy and faecal samples throughout different stages of colorectal cancer progression40,41,44,47, different subsets of colorectal cancer (for example, serrated neoplasia)48 and across patient populations, including American, European and Asian cohorts40,49, although some studies have not reproduced these observations (see Box 2). That such associations can be made and confirmed across these different tissue types and cohorts implies a robustness in the association between F. nucleatum and colorectal tumorigenesis that merits its continued study. Recent studies examining other cancer types have also reported F. nucleatum in oral, head and neck, oesophageal, cervical and gastric cancer tissues50–54. However, below, we focus on its role in colorectal cancer, as there is the most experimental support for a mechanistic role of F. nucleatum in driving tumorigenesis rather than acting as a microbial ‘passenger’ in this cancer type28.

Box 2 | reproducibility in microbiome and cancer research.

Detection of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer tissues across studies emerged as a challenge in the repass cancer replication study99,100 of the original 2012 study by Castellarin et al.41 and highlights the importance of reproducibility in science. this replication study, as part of the broader ‘reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology’, is an effort to replicate selected results from landmark publications in cancer biology101. a brief recap and contextualization of these two studies are as follows. in 2012, an rNa sequencing (rNa-seq)-based study found that F. nucleatum was enriched in colorectal cancer versus adjacent normal tissue, and DNa-based detection of F. nucleatum validated the rNa-seq-based findings41. similarly, an independent study also published in 2012 using different methodology also observed an enrichment of F. nucleatum DNa in colorectal cancer tissues compared with adjacent tissue using whole-genome shotgun sequencing and 16s ribosomal rNa (rrNa) gene amplicon survey data40.

The Repass replication study (proposed in 2016 and published in 2018) used flash-frozen samples from patients with colorectal cancer and from healthy controls, which were not included in the original Castellarin et al. study, but the replication study used the same primer and probe set. similar and disparate taqMan primer and probe sets have been used in a number of studies since the Castellarin et al. publication. Namely, some reports used primers that are specific to F. nucleatum whereas others used more general primers that detect many Fusobacterium spp. this distinction is not trivial, as one study demonstrated that the immunological associations they observed were specific to F. nucleatum and not generalizable to Fusobacterium spp. levels63. this situation is analogous to the difficulty of interpreting the presence and contribution of enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis and colibactin-producing Escherichia coli, which are also colorectal-cancer-associated bacteria, in 16s rrNa surveys, which cannot differentiate these strains from other, commensal B. fragilis and E. coli species that are normally found in the gut102,103. the stratification of tumours by F. nucleatum nucleic acid abundance has further limitations in that the distinction between _F. nucleatum_-high and _F. nucleatum_-low samples is subjective, especially as quantitative PCr (qPCr) values used to determine F. nucleatum levels approach the limit of detection100. Notably, a range in _Fusobacterium_-positive colorectal cancers, 3–56%, deemed positive for fusobacteria has been observed across studies, all of which have used formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPe) tissue58,61–64. the repass study did not observe the degree of enrichment of F. nucleatum in tumour versus adjacent normal colorectal tissue published in Castellarin et al. Given the differences observed across studies that have used different PCr-based methods and distinct sample types (FFPe versus flash-frozen), the extent to which Fusobacterium spp. are enriched in colorectal tumours varies across patient populations. stage, tumour location along the bowel and underlying genetics may be an underlying cause of these disparate observations. One critical question that emerged from these studies is whether fusobacterial nucleic acids are an appropriate metric at all. One recent study suggests that a ratio of F. nucleatum to other bacterial strains (for example, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii or Bifidobacterium spp.) measured by qPCr stool-based assay performs better as a potential diagnostic biomarker than F. nucleatum alone57.

Continued probing of human tissues has revealed features of the association between F. nucleatum and colorectal cancer that suggest additional complexity. First, F. nucleatum is often found co-occurring in tumours with other oral microorganisms, including Peptostreptococcus spp. and Leptotrichia spp., which mirrors how they are found interacting in the oral cavity46,55. F. nucleatum is also frequently found in the same tumours as Campylobacter spp.55, which are emerging as important gastrointestinal pathogens. Using microscopy on freshly resected tissues, researchers have shown that, in some patients, cancerous and nearby normal tissues harbour microorganisms that are arranged in highly organized, biofilm-like structures, which may influence how they contribute to tumorigenesis56. Such observations support the merits of continued research into how the conversations between these microorganisms, whether in the oral cavity or colorectal tumours, may function as a contributing factor to pathogenesis and/or a target for therapeutic interventions. Another avenue for further examination is a potential co-exclusionary relationship between certain microorganisms, such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and F. nucleatum, the latter of which harbours some bactericidal properties against these putative beneficial microorganisms57.

Although experimental research into the mechanisms by which F. nucleatum influences colorectal cancer is ongoing, epidemiological studies have enabled timely advances into the connections between intratumoural F. nucleatum levels and colorectal tumorigenesis. The most striking of these observations is that high F. nucleatum abundance is associated with poorer patient prognosis58 and cancer recurrence owing, in part, perhaps, to F. nucleatum promoting resistance to chemotherapy in colorectal cancer tissues59. By linking F. nucleatum abundance to specific tumour phenotypes, such research has further supported the hypothesis that F. nucleatum influences the tumour microenvironment in consistent ways that may be ultimately exploited to shape colorectal cancer treatment. _F. nucleatum_-high colonic lesions (either malignant or pre-malignant) have further been subtyped according to microsatellite stability58, Cpg island methylator phenotype (CIMP) status60,61, those bearing certain mutations (BRAF, KRAS, TP53 and others) and localization to the proximal versus transverse or sigmoid colon61,62. Collectively, these data support that there are links between F. nucleatum and tumour genetics and epigenetics that warrant further research. In the near future, tumoural microorganisms might be as influential as tumoural host genetics in guiding prognosis and treatment decisions, and microbial profiling may soon become as routine as tests of the genetic tumour profile. Tumours with a high F. nucleatum burden also have reduced T cell density63, supporting experimental research that F. nucleatum contributes to antitumour immunity. Epidemiological studies have also begun to address how exposures and lifestyle, such as diet and antibiotics, may influence F. nucleatum abundance in the setting of colorectal cancer64,65, prompting consideration of whether interventions designed to influence F. nucleatum levels in the body are beneficial for the prevention of colorectal cancer or detrimental to one’s native microbiota.

Mechanisms to promote cancer.

How does F. nucleatum, which is adapted to a life in the oral cavity, mechanistically influence colorectal tumorigenesis? Directed sequencing studies have suggested that intratumoural F. nucleatum strains have an oral origin, as patients who harbour F. nucleatum in their tumours also have oral F. nucleatum strains that share matching arbitrarily primed PCR strain-typing patterns66. However, such studies should be confirmed and merit further investigation with whole-genome sequencing to determine the true level of similarity between oral and tumoural strains. If one assumes that tumoural F. nucleatum originates in the oral cavity, then F. nucleatum must first migrate to dysplastic tissues to exert its effect on tumorigenesis. Colorectal cancer tissues overexpress a specific sugar residue, Gal-GalNAc67, which can be recognized by the fusobacterial adhesin Fap2, which also mediates co-aggregation and haemagglutination functions68,69. A study using an orthotopic graft model showed that F. nucleatum localized to colorectal tumours in an Fap2-dependent manner via a haematogenous route, which mimics the transient bacteraemia that can occur after flossing or dental procedures70,71. However, F. nucleatum has been found in colorectal cancer tissues at early stages of tumorigenesis44 before Gal-GalNAc overexpression, suggesting that there may be multiple routes by which localization to the developing tumour microenvironment occurs. In experiments using the genetic Apc Min/+ model, in which mice spontaneously develop intestinal tumours72,73, oral instillation of F. nucleatum was sufficient to potentiate colorectal tumour development, suggesting that an oral–gastrointestinal route is another possibility74,75. F. nucleatum is considered to be an active invader of host cells. It encodes an array of genes related to adhesion and invasion9, enabling it to reside intracellularly in tumour cells, and, once there, potentially affecting the mechanisms by which it can influence tumorigenesis.

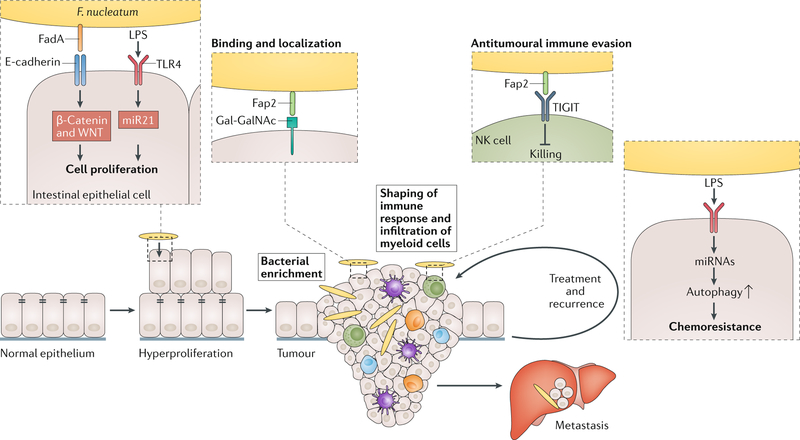

The spectrum of host processes that drive tumorigenesis, from mutations and genome instability to immune evasion, have been well described76. What remains less clear is the breadth of these pathways that can be influenced by cancer-associated microorganisms such as F. nucleatum. Other colorectal-cancer-associated micro-organisms, such as enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis and colibactin-producing Escherichia coli, produce toxins that either change the immune response or damage DNA, respectively75,77. Although epidemiological associations suggest that F. nucleatum can promote genome instability and mutation60, F. nucleatum encodes no known toxins and very few canonical ‘virulence factors’9,10,78. Despite the resistance of F. nucleatum to genetic manipulation (see Box 3), researchers have made substantial progress into different mechanisms by which F. nucleatum may shape the tumour microenvironment (fig. 3).

Box 3 | Tools and methodological approaches for studying fusobacterial biology.

The study of fusobacterial biology has been restricted to this point by the limited genetic tractability of these strains. in the published literature, only four strains have been mutagenized: Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum strains atCC 23726 (ref.104) and atCC 25586 (ref.105); F. nucleatum subsp. polymorphum atCC 10953 (ref.17) by electroporation; and F. nucleatum subsp. polymorphum 12230 by sonoporation106. this technical hurdle is multifactorial. Hypothesized biological limitations have included strain-intrinsic restriction endonuclease activity in response to different methylation patterns of heterologous DNa as well as that most constructs currently used are derived from constructs that were designed originally for Clostridium spp. given their comparably low GC content and similar codon biases. therefore, instead of genetic manipulation of F. nucleatum, researchers have used alternative approaches to mechanistically study specific adhesins and enzymes, such as heterologous expression of fusobacterial proteins in other species, including Lactobacillus spp. and Escherichia coli17,106–108.

The clostridial research field has a more developed genetic toolkit, perhaps because of the comparably larger scientific community, whereas many of the tools still in use today in fusobacterial research were generated by susan Kinder Haake, a pioneer in fusobacterial genetics and a master tool-builder in this field. after her death, the continued development of such resources with an eye towards broader community implementation stagnated until recently. two studies have now demonstrated transposon mutagenesis in F. nucleatum atCC 23726 (refS68,109), the most genetically tractable strain described to date. Even more impressively, Wu et al.109 have developed techniques to rapidly generate in-frame, nonpolar deletions, whereas most of the previously reported _F. nucleatum_-directed mutants were insertional (Campbell) mutants, which are often polar and prone to reversion without antibiotic selection. antibiotic-marked deletion and complementation fusobacterial strains have previously been generated using a unique sonoporation-based method, but to date, this approach has been successfully reported only in F. nucleatum by one laboratory30,110. An important caveat to these studies is that F. nucleatum atCC 23726 is neither an oral nor gastrointestinal isolate but has an urogenital origin; therefore, its applicability to the study of different host–microorganism interactions may be limited. Furthermore, strain usage within and across studies has been inconsistent throughout F. nucleatum studies, and especially in the quickly expanding F. nucleatum colorectal cancer field (supplementary table 1). when an observation, such as increased host cell proliferation, is confirmed with distinct F. nucleatum isolates across laboratories, these studies underscore the robustness of an observed biological effect59,79,111. However, the diversity of strains used across these works can also complicate generating a comprehensive model of how F. nucleatum potentiates colorectal cancer. For example, a mechanism by which F. nucleatum shapes the tumour microenvironment may be strain-specific, as has been previously observed for phenotypes in the oral setting, such as fusobacterial co-aggregation with other bacteria112. this issue has already surfaced in the tumour-specific literature with conflicting observations in animal models of tumorigenesis using different F. nucleatum isolates45,69,74,79,113.

In parallel to the ongoing development of more effective traditional tools (for example, forward genetics approaches) for fusobacterial genetics, the implementation of methods used in other microorganisms to advance the study of F. nucleatum in host–microorganism interactions is desperately needed. CrisPr–Cas9 technologies may enable expedient deletions and defined library generation of F. nucleatum mutants that could serve as a community resource. Chemical mutagenesis in conjunction with deep sequencing, using methods described for genetically recalcitrant or intracellular bacteria such as Chlamydia trachomatis114, could provide a much-needed breakthrough in understanding the niche specialization of F. nucleatum.

Fig. 3. Mechanisms by which Fusobacterium nucleatum may contribute to colorectal carcinogenesis.

Accumulating evidence suggests that Fusobacterium nucleatum influences many stages of colorectal cancer progression. First, F. nucleatum can increase cell proliferation in cancer cells through two distinct mechanisms: the binding of FadA to E-cadherin drives activation of the β-catenin and Wnt pathway79, and activation of TLR4 and NF-κB results in increased expression of the oncogenic microRNA miR21 (ref.111). These observations are supported by work in the Apc Min/+ mouse model of intestinal tumorigenesis, in which F. nucleatum administration resulted in more aberrant crypt foci and high-grade dysplasia, both early stages of tumorigenesis74. Once the tumour has developed, F. nucleatum can localize to the Gal-GalNAc-expressing tumour cells through binding of its Fap2 lectin, which results in enrichment of F. nucleatum69. F. nucleatum functionally modifies the tumour microenvironment by influencing the accumulation of myeloid cells74 and blocking antitumoural immune responses of natural killer (NK) cells45. F. nucleatum may also affect metastatic dissemination as it can be isolated from liver and lymph node metastases40,41,46. Once colorectal cancer is identified and treated, F. nucleatum is associated with increased risk of recurrence and the development of chemoresistance by suppressing specific miRNAs involved in autophagy59. LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

Cancer is, at its simplest, uncontrolled cell growth, and F. nucleatum may influence the proliferation of colorectal cancer cells, either in pure cell culture59,79 or in ex vivo xenografts46. Antibiotic treatment disrupted tumour growth in mice with _F. nucleatum_-bearing patient-derived colorectal cancer xenografts and reduced fusobacterial burden and cell proliferation46. Work in cancer cell lines has provided a potential mechanism for such cancer-promoting effects, as FadA interacts with E-cadherin, leading to β-catenin activation and sub-sequent activation of Wnt target genes79, an important pathway in cell development that is often dysregulated in cancer80. Another axis of cancer development and progression that F. nucleatum influences is the creation of a pro-inflammatory tumour milieu. Using the same Apc Min/+ model in which mice fed F. nucleatum developed more colorectal and small intestinal tumours than their sham-fed counterparts, researchers also observed more intratumoural myeloid cells, including macrophages, dendritic cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and this response was specific to F. nucleatum74. In this model, F. nucleatum also activated the NF-κB pathway and induced expression of the genes encoding several pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-1β, which mirrors human RNA-seq data from patients bearing high F. nucleatum loads in their colorectal tumours74. A third mechanism by which F. nucleatum shapes the tumour microenvironment is by evading anti-cancer immune responses. Fap2, the same adhesin that may mediate recognition and binding of the bacterium to colorectal cancer tissue, can bind a human receptor known as TIGIT that is expressed on natural killer (NK) cells and other tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes45. TIGIT inhibits the cytotoxic function of these cells and thereby protects both F. nucleatum and nearby tumour cells from being killed by immune cells81. These three examples demonstrate just a snapshot of the diverse ways by which F. nucleatum can promote a pro-tumourigenic environment, and there are undoubtedly others that remain to be discovered.

Diagnostics and therapeutic approaches

Intrinsic to development of any fusobacterial diagnostic are two overarching questions: is F. nucleatum a biological marker for colorectal tumours and what is a robust, objective measure of F. nucleatum (see Box 4)? Faecal-based tests are used globally to screen for colorectal cancer. The most widely used test detects blood that is hidden in the stool (occult blood). Although this is a helpful screening test, the test is not specific as occult blood in the stool can be a harbinger of many diseases, not only colorectal cancer. Furthermore, in some faecal-based tests, many ingested substances can lead to a false-positive result. However, newer tests have increased the sensitivity and specificity for detecting occult blood, and some even detect DNA mutations in host cells shed into the stool. Adding microbial biomarkers (see Box 4), such as the faecal abundance of F. nucleatum, may provide much-needed progress in the ability to non-invasively screen for colorectal cancer. Beyond stool-based diagnostics, detection of IgA or IgG antibodies against F. nucleatum in the serum also has potential as a diagnostic82. However, population-based studies are required to further vet the specificity and sensitivity of a serum antibody-based test, and the genetic and antigenic diversity of F. nucleatum as well as a prior history of periodontitis or other fusobacterial infections may be confounding factors.

Box 4 | Faecal Fusobacterium nucleatum: how does one assess a biomarker?

Ideal biological markers (biomarkers) can result in efficient diagnosis with high sensitivity and specificity, can inform disease prognosis, and may provide valuable input guiding therapeutic decisions. there has been tremendous and longstanding interest in non-invasive biomarkers that use stool or serum for diagnosis of colorectal cancer115,116. Given the links between Fusobacterium nucleatum and colorectal cancer, there has also been interest in the presence of F. nucleatum DNa and cells in stool and intestinal tissues and of antibodies against F. nucleatum as biomarkers of colorectal tumours and as prognostic factors in established colorectal cancer.

There have been a handful of studies characterizing the microbiome of colorectal adenomas and cancer40,41,44,117. to increase the power of these admittedly small population studies (from dozens to hundreds of samples), a few individual research groups have undertaken meta-analyses to improve estimates of F. nucleatum presence in the stool and tissue, when colorectal cancer has been diagnosed. A meta-analysis from 2018 examined ten studies (seven peer-reviewed articles) that together included 629 patients with colorectal cancer and 569 healthy controls. in this meta-analysis, most studied subjects were from China, most of the samples were faecal and the measurement assays were mostly based on quantitative PCr (qPCr). the area under the curve (auC) of the receiver operator characteristic (rOC) curve was 0.86 (95% Ci 0.83–0.89), suggesting that F. nucleatum may be a good biomarker for colorectal cancer in some populations118. in general, an auC <0.5 suggests that a biomarker has no diagnostic value and an auC >0.90 suggests an excellent diagnostic value, with an auC of 0.75–0.9 falling in the range of good and 0.50–0.75 representing poor value. rOC curves are generated by graphing the true-positive rate (sensitivity) on the _y_-axis and 1 – the true-negative rate (specificity) on the _x_-axis at a variety of ‘cut-off’ values that distinguish healthy versus sick or, in this case, the absence versus presence of cancer. another 2018 meta-analysis (seven studies, six peer-reviewed publications) that exclusively focused on faecal F. nucleatum studies had a lower auC (0.8) and less encouraging specificity and sensitivity metrics overall. However, a subgroup analysis of studies with ≥50 asian subjects demonstrated improved specificity (0.85, 95% Ci 0.80–0.88)119. in complete contrast was another meta-analysis of 14 studies including over 1,700 faecal samples (16s ribosomal rNa (rrNa) gene amplicon surveys) and 492 intestinal tissue samples from 350 individuals in which neither Fusobacterium spp. nor F. nucleatum emerged as biomarkers for colorectal adenocarcinoma120. Furthermore, in this meta-analysis, all individual fusobacterial taxa performed poorly in differentiating subjects that were healthy from those that had colorectal cancer, with auCs around 0.5–0.75. there was limited study overlap across these three meta-analyses regarding the method of microbial detection (qPCr versus 16s rrNa gene amplicon surveys). For a disease as prevalent as colorectal cancer, a much larger population-scale study (on the order of hundreds of thousands) would need to be undertaken to evaluate F. nucleatum as a diagnostic biomarker. Given that there might be differences due to subject ethnicity or geography, a global cohort would be ideal. Furthermore, the method of detection would not be a trivial decision.

Effective tests designed to detect F. nucleatum in stool or tissue may have other uses beyond diagnosis. A high abundance of tumoural F. nucleatum may influence overall survival58; thus, tumoural levels of F. nucleatum may some-day guide prognosis. Some studies suggest that there may be associations between the abundance of F. nucleatum and the genetic landscape of the tumour, which suggests that the effect of F. nucleatum on prognosis may not be a direct association. It remains understudied, but of interest, how the status of KRAS and TP53 mutations, the presence of microsatellite instability and epigenetic dysregulation within a tumour (for example, CIMP)60 affect and influence the tumoural load of F. nucleatum. A recent study suggested that patients with familial adenomatous polyposis with congenital APC mutations had undetectable levels of F. nucleatum in their tumours83, which suggests that host genetics may have a role in shaping the burden of F. nucleatum. However, F. nucleatum did potentiate tumorigenesis in mouse models harbouring Apc mutations74,84. F. nucleatum seems to influence tumoural infiltration of myeloid cells74, T cell phenotypes63 and the cytotoxic activity of NK cells45. Such findings ultimately may influence the types of immunotherapies offered to patients with colorectal cancer in the future85. Similarly, when investigators delved into why F. nucleatum was abundant in the colorectal cancer tissue of patients whose cancer recurred after chemotherapy, they found that F. nucleatum may modulate resistance to chemotherapy by activating autophagy and impairing chemotherapy-induced cancer cell death59. These provocative findings not only may explain the correlation between the abundance of F. nucleatum and prognosis but also raise the question of whether patients with a high abundance of F. nucleatum at diagnosis might benefit from a _F. nucleatum-_directed therapy before, or concomitant with, conventional chemotherapy. There is an urgent need for both discovery-oriented and translational research focused on how the composition and function of the gut and tumoural microbiota affect not only the efficacy of chemotherapy, radiation therapy and immunotherapy but also the adverse events associated with such treatments.

If F. nucleatum influences the outcome of colorectal cancer, the response to cancer treatment and the risk of pre-term labour, then expanding the anti-F. nucleatum therapeutic armamentarium is worth considering. In general, most clinical isolates of F. nucleatum are sensitive to a number of antibiotics, including metronidazole, clindamycin and a number of β-lactam antibiotics with the exception of penicillin, for which resistance has been reported86. In patient-derived xenograft models of colorectal cancer that showed an enrichment of F. nucleatum, treatment with metronidazole reduced tumour volumes46. However, metronidazole broadly targets anaerobic bacteria; therefore, implementing such an intervention would be problematic in numerous ways as anaerobic bacteria also improve responses to chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Thus, a narrow-spectrum antibiotic that is specific for F. nucleatum and ideally targets only the tumour tissue would be of interest, especially given the mutualistic role of F. nucleatum in the oropharynx. However, owing to concerns about antibiotic resistance for both broad-spectrum and narrow-spectrum antibiotics, antivirulence strategies may be more opportune. The F. nucleatum adhesin Fap2 may be an attractive target as its lectin activities seem to promote enrichment of F. nucleatum in tumoural tissues69 and as it also compromises antitumour immunity45.

Given the global health burden of both pre-term birth and colorectal cancer, an _F. nucleatum_-directed vaccine warrants consideration not only in high-risk populations but potentially in larger populations. F. nucleatum vaccination has already been tried to combat breath malodour. These halitosis vaccines have targeted FomA, an outer membrane protein expressed by F. nucleatum, which functions in bacterial co-aggregation and biofilm formation87. Unfortunately, no outcome data have been published on whether individuals receiving the vaccines for halitosis had a lowered incidence of colorectal cancer. A recent study investigated whether immunization with alkyl hydroperoxide reductase sub-unit C (AhpC) from F. nucleatum could protect mice from infection with the bacterium88. The vaccination lowered levels of F. nucleatum in intestinal tissues in intragastrically inoculated mice and elicited IgA and IgG responses. Given the sophisticated methods used by modern-day vaccinologists to elicit specific types of immune responses (humoral versus T cell responses) and that some F. nucleatum strains have an intracellular phase29, T cell-inducing vaccines similar to those targeting tuberculosis and malaria might represent a preferable strategy for F. nucleatum. Another approach that is gaining in enthusiasm is phage-based therapeutics, not only because of multidrug resistance but also because of the exquisite selectivity of phages. However, the intracellular phase of some F. nucleatum strains could present barriers for effective phage therapy, and the number of distinct F. nucleatum strains found in colorectal cancer tissues might also pose a challenge. Nevertheless, the potential of phage-based therapeutics is tantalizing, especially for multidrug-resistant bacteria. Another option to change the tumoural and other human microbiota that potentially harbour F. nucleatum is microbial ecosystem replacement therapy, which uses consortia of designer microorganisms or carefully curated cocktails of human-derived isolates89. Such approaches are in clinical trial for infection with Clostridium difficile and could potentially be used to exclude F. nucleatum. In summary, a gamut of potential therapeutics could be used to target F. nucleatum, relying on traditional and more innovative approaches and targeting F. nucleatum, the microbiota and/or the host.

Conclusions

F. nucleatum is a multifaceted bacterium that engages in diverse interactions with other microorganisms and humans that range from beneficial to detrimental in nature. More and more, as we study diseases linked to members of the microbiota, it is tempting to jump rapidly to clinical applications. However, both robust experimental approaches, be it within human cohorts or preclinical models, and reproducible results across microbiota studies are pivotal to bridge the translational gap and ensure that data are neither lost in translation nor mistranslated clinically.

As has been observed for the cancer-associated bacterium H. pylori in the setting of the stomach, disruption of co-evolved symbioses can have unintended consequences, as the presence of H. pylori seems to have protective effects for other diseases such as allergy90,91, and not all strains of H. pylori are oncogenic. Control, elimination and eradication efforts may be appropriate to defeat some infectious diseases such as malaria, but considering elimination of bacteria such as F. nucleatum to prevent associated conditions including colorectal cancer may be premature. Before we consider such _F. nucleatum_-targeted treatments, we must uncover more about the basic biology of F. nucleatum, in both its natural niche and in other, potentially disease-associated, locations, and about how it influences the host cells and other microorganisms with which it is in intimate association. We must address how to define causation by F. nucleatum in the numerous diseases with which it is associated. We must better appreciate who is at risk of _F. nucleatum_-associated diseases such as colorectal cancer. Whereas F. nucleatum is fairly ubiquitous in the oral cavity, its usually low levels in the gut are increased in patients with inflammatory bowel disease43 and can be modulated by factors such as diet92. Understanding how F. nucleatum strains and levels in the mouth and gut affect the risk of colorectal cancer may inform suitable candidates for interventions focused on the modulation of F. nucleatum. Only by continuing to investigate F. nucleatum across the gamut of its mutualistic and pathogenic lifestyles will we discover the divergent pathways that may be leveraged for diagnostic, preventive and therapeutic purposes.

Supplementary Material

supplemental

Combinatorial labelling and spectral imaging– fluorescence in situ hybridization

(CLASI-FISH). This technique enables detection of ten to several hundred distinct microbial taxa by using combinations of fluorophores coupled to different oligonucleotide probes that target unique regions of the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene.

Osteomyelitis

Infectious or non-infectious inflammation of the bone.

Pericarditis

Infectious or non-infectious inflammation of the sac-like tissue that surrounds the heart.

Chorioamnionitis

Infectious or non-infectious inflammation of the chorion and amnion (the fetal membranes) and the amniotic fluid, which can occur before or during labour.

Lemierre syndrome

Infectious thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, which is often caused by F. necrophorum. it can occur in the setting of a fusobacterial throat infection with peritonsillar abscess formation, but in the modern antibiotic era it remains fairly rare. The syndrome is named after Andrew Lemierre, who published a case report in the 1930s that identified throat infections as the cause of several anaerobic sepsis cases.

CpG island methylator phenotype

(CIMP). A state of epigenetic instability in which promoter Cpg island sites become hypermethylated, which results in turning off of genes, including tumour suppressor genes.

Microsatellite instability

A condition in which impaired DNA mismatch repair leads to genetic hypermutation. Colorectal tumours can be described as microsatellite instable-high (MSi-high) or microsatellite stable (MSS).

Familial adenomatous polyposis

A genetic disorder that is caused by mutation of the APC gene and results in numerous tumours of the large bowel. Classically, these colon tumours form during the teenage years and the number of tumours increases with age, but there are also attenuated variants.

Colorectal adenomas

Non-malignant tumours occurring in the colon and rectum that can develop into cancer.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01CA154426. C.A.B. is the Dennis and Marsha Dammerman fellow of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (DRG-2205–14).

Footnotes

Competing interests

W.S.G. serves on the Scientific Advisory Boards of Evelo Biosciences, Kintai Therapeutics and uBiome. W.S.G. is a consultant for BioMx and has been a consultant for Janssen, Pfizer and Merck. W.S.G. is a senior editor at eLife, which publishes the ‘Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology’ experimental designs and methods as registered reports and results as replication studies.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hug LA et al. A new view of the tree of life. Nat. Microbiol 1, 16048 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parks DH et al. Recovery of nearly 8,000 metagenome-assembled genomes substantially expands the tree of life. Nat. Microbiol 2, 1533–1542 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao J-S, Manno D & Hawari J Psychrilyobacter atlanticus gen. nov., sp. nov., a marine member of the phylum Fusobacteria that produces H2 and degrades nitramine explosives under low temperature conditions. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 59, 491–497 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolenbrander PE, Palmer RJ, Periasamy S & Jakubovics NS Oral multispecies biofilm development and the key role of cell-cell distance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 8, 471–480 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lancy P, Dirienzo JM, Appelbaum B, Rosan B & Holt SC Corncob formation between Fusobacterium nucleatum and Streptococcus sanguis. Infect. Immun 40, 303–309 (1983). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo L, Shokeen B, He X, Shi W & Lux R Streptococcus mutans SpaP binds to RadD of Fusobacterium nucleatum ssp. polymorphum. Mol. Oral Microbiol 32, 355–364 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan CW, Lux R, Haake SK & Shi W The Fusobacterium nucleatum outer membrane protein RadD is an arginine-inhibitable adhesin required for interspecies adherence and the structured architecture of multispecies biofilm. Mol. Microbiol 71, 35–47 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu T et al. Cellular components mediating coadherence of Candida albicans and Fusobacterium nucleatum. J. Dent. Res 94, 1432–1438 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manson McGuire A et al. Evolution of invasion in a diverse set of Fusobacterium species. MBio 5, e01864 (2014).This publication is a comparative genomic analysis of sequenced Fusobacterium species focused on potential mechanisms of molecular pathogenesis.

- 10.Zanzoni A, Spinelli L, Braham S & Brun C Perturbed human sub-networks by Fusobacterium nucleatum candidate virulence proteins. Microbiome 5, 89 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan KH et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis and Treponema denticola exhibit metabolic symbioses. PLOS Pathog 10, e1003955 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakanaka A, Kuboniwa M, Takeuchi H, Hashino E & Amano A Arginine-ornithine antiporter ArcD controls arginine metabolism and interspecies biofilm development of Streptococcus gordonii. J. Biol. Chem 290, 21185–21198 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendrickson EL et al. Proteomics of Fusobacterium nucleatum within a model developing oral microbial community. Microbiologyopen 3, 729–751 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mark Welch JL, Rossetti BJ, Rieken CW, Dewhirst FE & Borisy GG Biogeography of a human oral microbiome at the micron scale. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E791–E800 (2016).This publication is a technical re-exploration of the spatial organization of the microbiota in the oral cavity, revealing new layers of complexity.

- 15.Krisanaprakornkit S et al. Inducible expression of human beta-defensin 2 by Fusobacterium nucleatum in oral epithelial cells: multiple signaling pathways and role of commensal bacteria in innate immunity and the epithelial barrier. Infect. Immun 68, 2907–2915 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahn S-H et al. Transcriptome profiling analysis of senescent gingival fibroblasts in response to Fusobacterium nucleatum infection. PLOS ONE 12, e0188755 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhattacharyya S et al. FAD-I, a Fusobacterium nucleatum cell wall-associated diacylated lipoprotein that mediates human beta defensin 2 induction through Toll-like receptor-½ (TLR-½) and TLR-2/6. Infect. Immun 84, 1446–1456 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallimidi AB et al. Periodontal pathogens Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum promote tumor progression in an oral-specific chemical carcinogenesis model. Oncotarget 6, 22613–22623 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park S-R et al. Diverse Toll-like receptors mediate cytokine production by Fusobacterium nucleatum and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans in macrophages. Infect. Immun 82, 1914–1920 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taxman DJ et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis mediates inflammasome repression in polymicrobial cultures through a novel mechanism involving reduced endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem 287, 32791–32799 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saito A et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis entry into gingival epithelial cells modulated by Fusobacterium nucleatum is dependent on lipid rafts. Microb. Pathog 53, 234–242 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metzger Z et al. Synergistic pathogenicity of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum in the mouse subcutaneous chamber model. J. Endod 35, 86–94 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swidsinski A et al. Acute appendicitis is characterised by local invasion with Fusobacterium nucleatum/necrophorum. Gut 60, 34–40 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han XY et al. Fusobacterial brain abscess: a review of five cases and an analysis of possible pathogenesis. J. Neurosurg 99, 693–700 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregory SW, Boyce TG, Larson AN, Patel R & Jackson MA Fusobacterium nucleatum osteomyelitis in 3 previously healthy children: a case series and review of the literature. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc 4, e155–e159 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Truant AL, Menge S, Milliorn K, Lairscey R & Kelly MT Fusobacterium nucleatum pericarditis. J. Clin. Microbiol 17, 349–351 (1983). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altshuler G & Hyde S Clinicopathologic considerations of fusobacteria chorioamnionitis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand 67, 513–517 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tjalsma H, Boleij A, Marchesi JR & Dutilh BE A bacterial driver-passenger model for colorectal cancer: beyond the usual suspects. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 10, 575–582 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strauss J et al. Invasive potential of gut mucosa-derived Fusobacterium nucleatum positively correlates with IBD status of the host. Inflamm. Bowel Dis 17, 1971–1978 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikegami A, Chung P & Han YW Complementation of the fadA mutation in Fusobacterium nucleatum demonstrates that the surface-exposed adhesin promotes cellular invasion and placental colonization. Infect. Immun 77, 3075–3079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han YW et al. Interactions between periodontal bacteria and human oral epithelial cells: Fusobacterium nucleatum adheres to and invades epithelial cells. Infect. Immun 68, 3140–3146 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinder Haake S & Lindemann RA Fusobacterium nucleatum T18 aggregates human mononuclear cells and inhibits their PHA-stimulated proliferation. J. Periodontol 68, 39–44 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gursoy UK, Könönen E & Uitto V-J Intracellular replication of fusobacteria requires new actin filament formation of epithelial cells. APMIS 116, 1063–1070 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss EI et al. Attachment of Fusobacterium nucleatum PK1594 to mammalian cells and its coaggregation with periodontopathogenic bacteria are mediated by the same galactose-binding adhesin. Oral Microbiol. Immunol 15, 371–377 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han YW et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces premature and term stillbirths in pregnant mice: implication of oral bacteria in preterm birth. Infect. Immun 72, 2272–2279 (2004).This publication provides evidence in a preclinical model to support the association of fusobacteria with adverse pregnancy outcomes in humans.

- 36.Xu M et al. FadA from Fusobacterium nucleatum utilizes both secreted and nonsecreted forms for functional oligomerization for attachment and invasion of host cells. J. Biol. Chem 282, 25000–25009 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fardini Y et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum adhesin FadA binds vascular endothelial cadherin and alters endothelial integrity. Mol. Microbiol 82, 1468–1480 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aagaard K et al. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci. Transl Med 6, 237ra65 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hatakeyama M Helicobacter pylori CagA and gastric cancer: a paradigm for hit-and-run carcinogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 15, 306–316 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kostic AD et al. Genomic analysis identifies association of Fusobacterium with colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res 22, 292–298 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castellarin M et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res 22, 299–306 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gevers D et al. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset Crohn’s disease. Cell Host Microbe 15, 382–392 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pascal V et al. A microbial signature for Crohn’s disease. Gut 66, 813–822 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCoy AN et al. Fusobacterium is associated with colorectal adenomas. PLOS ONE 8, e53653 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gur C et al. Binding of the Fap2 protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum to human inhibitory receptor TIGIT protects tumors from immune cell attack. Immunity 42, 344–355 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bullman S et al. Analysis of Fusobacterium persistence and antibiotic response in colorectal cancer. Science 358, 1443–1448 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng Q et al. Gut microbiome development along the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Nat. Commun 6, 6528 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu J et al. Invasive Fusobacterium nucleatum may play a role in the carcinogenesis of proximal colon cancer through the serrated neoplasia pathway. Int. J. Cancer 139, 1318–1326 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y-Y et al. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum infection with colorectal cancer in Chinese patients. World J. Gastroenterol 22, 3227–3233 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Hebshi NN et al. Inflammatory bacteriome featuring Fusobacterium nucleatum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa identified in association with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep 7, 1834 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao H et al. Variations in oral microbiota associated with oral cancer. Sci. Rep 7, 11773 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Audirac-Chalifour A et al. Cervical microbiome and cytokine profile at various stages of cervical cancer: a pilot study. PLOS ONE 11, e0153274 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hsieh Y-Y et al. Increased abundance of Clostridium and Fusobacterium in gastric microbiota of patients with gastric cancer in Taiwan. Sci. Rep 8, 158 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamura K et al. Human microbiome Fusobacterium nucleatum in esophageal cancer tissue is associated with prognosis. Clin. Cancer Res 22, 5574–5581 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Warren RL et al. Co-occurrence of anaerobic bacteria in colorectal carcinomas. Microbiome 1, 16 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dejea CM et al. Microbiota organization is a distinct feature of proximal colorectal cancers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 18321–18326 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo S et al. A simple and novel fecal biomarker for colorectal cancer: ratio of Fusobacterium nucleatum to probiotics populations, based on their antagonistic effect. Clin. Chem 64, 1327–1337 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mima K et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue and patient prognosis. Gut 65, 1973–1980 (2015).This molecular epidemiology study highlights the association of tumoural fusobacterial levels with worse prognosis in colorectal cancer.

- 59.Yu T et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes chemoresistance to colorectal cancer by modulating autophagy. Cell 170, 548–563 (2017).This work explores the links between fusobacteria, colon cancer and autophagy, suggesting that fusobacteria may confer chemoresistance in colon cancers.

- 60.Tahara T et al. Fusobacterium in colonic flora and molecular features of colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Res 74, 1311–1318 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ito M et al. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum with clinical and molecular features in colorectal serrated pathway. Int. J. Cancer 137, 1258–1268 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mima K et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue according to tumor location. Clin. Transl Gastroenterol 7, e200 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mima K et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum and T cells in colorectal carcinoma. JAMA Oncol 1, 653–661 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mehta RS et al. Association of dietary patterns with risk of colorectal cancer subtypes classified by Fusobacterium nucleatum in tumor tissue. JAMA Oncol 3, 921–927 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu L et al. Diets that promote colon inflammation associate with risk of colorectal carcinomas that contain Fusobacterium nucleatum. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 16, 1622–1631 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Komiya Y et al. Patients with colorectal cancer have identical strains of Fusobacterium nucleatum in their colorectal cancer and oral cavity. Gut 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316661 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Yang GY & Shamsuddin AM Gal-GalNAc: a biomarker of colon carcinogenesis. Histol. Histopathol 11, 801–806 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Coppenhagen-Glazer S et al. Fap2 of Fusobacterium nucleatum is a galactose-inhibitable adhesin involved in coaggregation, cell adhesion, and preterm birth. Infect. Immun 83, 1104–1113 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abed J et al. Fap2 mediates Fusobacterium nucleatum colorectal adenocarcinoma enrichment by binding to tumor-expressed Gal-GalNAc. Cell Host Microbe 20, 215–225 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carroll GC & Sebor RJ Dental flossing and its relationship to transient bacteremia. J. Periodontol 51, 691–692 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lockhart PB et al. Bacteremia associated with toothbrushing and dental extraction. Circulation 117, 3118–3125 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Su LK et al. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science 256, 668–670 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moser AR, Pitot HC & Dove WF A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Science 247, 322–324 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kostic AD et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 14, 207–215 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wu S et al. A human colonic commensal promotes colon tumorigenesis via activation of T helper type 17 T cell responses. Nat. Med 15, 1016–1022 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hanahan D & Weinberg RA Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nougayrède J-P et al. Escherichia coli induces DNA double-strand breaks in eukaryotic cells. Science 313, 848–851 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sanders BE, Umana A, Lemkul JA & Slade DJ FusoPortal: an interactive repository of hybrid MinION-sequenced fusobacterium genomes improves gene identification and characterization. mSphere 3, 284 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rubinstein MR et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe 14, 195–206 (2013).This publication and reference 74 are seminal papers supporting that fusobacteria potentiate colonic tumorigenesis.

- 80.White BD, Chien AJ & Dawson DW Dysregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in gastrointestinal cancers. Gastroenterology 142, 219–232 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dougall WC, Kurtulus S, Smyth MJ & Anderson AC TIGIT and CD96: new checkpoint receptor targets for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol. Rev 276, 112–120 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang H-F et al. Evaluation of antibody level against Fusobacterium nucleatum in the serological diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep 6, 33440 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dejea CM et al. Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis harbor colonic biofilms containing tumorigenic bacteria. Science 359, 592–597 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu Y et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis in mice via a Toll-like receptor 4/p21-activated kinase 1 cascade. Dig. Dis. Sci 63, 1210–1218 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Routy B et al. The gut microbiota influences anticancer immunosurveillance and general health. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 15, 382–396 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bennett JE, Dolin R & Blaser MJ Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Disease (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu P-F, Huang I-F, Shu C-W & Huang C-M Halitosis vaccines targeting FomA, a biofilm-bridging protein of fusobacteria nucleatum. Curr. Mol. Med 13, 1358–1367 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guo S-H et al. Immunization with alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C reduces Fusobacterium nucleatum load in the intestinal tract. Sci. Rep 7, 10566 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Petrof EO, Claud EC, Gloor GB & Allen-Vercoe E Microbial ecosystems therapeutics: a new paradigm in medicine? Benef. Microbes 4, 53–65 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Blaser MJ Helicobacter pylori and esophageal disease: wake-up call? Gastroenterology 139, 1819–1822 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Blaser MJ Helicobacter pylori eradication and its implications for the future. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther 11 (Suppl. 1), 103–107 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.O’Keefe SJD et al. Fat, fibre and cancer risk in African Americans and rural Africans. Nat. Commun 6, 6342 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Duncan SH, Hold GL, Harmsen HJM, Stewart CS & Flint HJ Growth requirements and fermentation products of Fusobacterium prausnitzii, and a proposal to reclassify it as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii gen. nov., comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 52, 2141–2146 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jalava J & Eerola E Phylogenetic analysis of Fusobacterium alocis and Fusobacterium sulci based on 16S rRNA gene sequences: proposal of Filifactor alocis (Cato, Moore and Moore) comb. nov. and Eubacterium sulci (Cato, Moore and Moore) comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol 49, 1375–1379 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Todd SM, Settlage RE, Lahmers KK & Slade DJ Fusobacterium genomics using MinION and illumina sequencing enables genome completion and correction. mSphere 3, 284 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gupta RS & Sethi M Phylogeny and molecular signatures for the phylum Fusobacteria and its distinct subclades. Anaerobe 28, 182–198 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nie S et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum subspecies identification by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol 53, 1399–1402 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kook J-K et al. Genome-based reclassification of Fusobacterium nucleatum subspecies at the species level. Curr. Microbiol 74, 1137–1147 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Repass J, Maherali N & Owen K Reproducibility project: cancer biology. Registered report: Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. eLife 5, 427 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Repass J et al. Replication study: Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. eLife 7, e64900 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Errington TM et al. An open investigation of the reproducibility of cancer biology research. eLife 3, 5773 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Boleij A et al. The Bacteroides fragilis toxin gene is prevalent in the colon mucosa of colorectal cancer patients. Clin. Infect. Dis 60, 208–215 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Arthur JC et al. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science 338, 120–123 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kinder-Haake S, Yoder S & Hunt Gerardo S Efficient gene transfer and targeted mutagenesis in Fusobacterium nucleatum. Plasmid 55, 27–38 (2006).This foundational paper establishes techniques for genetic manipulation of fusobacteria.

- 105.Nakagaki H et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum envelope protein FomA is immunogenic and binds to the salivary statherin-derived peptide. Infect. Immun 78, 1185–1192 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Han YW et al. Identification and characterization of a novel adhesin unique to oral fusobacteria. J. Bacteriol 187, 5330–5340 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Casasanta MA et al. A chemical and biological toolbox for Type Vd secretion: characterization of the phospholipase A1 autotransporter FplA from Fusobacterium nucleatum. J. Biol. Chem 292, 20240–20254 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ma L, Ding Q, Feng X & Li F The protective effect of recombinant FomA-expressing Lactobacillus acidophilus against periodontal infection. Inflammation 36, 1160–1170 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wu C et al. Forward genetic dissection of biofilm development by Fusobacterium nucleatum: novel functions of cell division proteins FtsX and EnvC. MBio 9, 101 (2018).This recent publication expands the fusobacterial genetic toolkit.

- 110.Han YW, Ikegami A, Chung P, Zhang L & Deng CX Sonoporation is an efficient tool for intracellular fluorescent dextran delivery and one-step double-crossover mutant construction in Fusobacterium nucleatum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 73, 3677–3683 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yang Y et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum increases proliferation of colorectal cancer cells and tumor development in mice by activating Toll-like receptor 4 signaling to nuclear factor-κB, and up-regulating expression of MicroRNA-21. Gastroenterology 152, 851–866 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kolenbrander PE, Andersen RN & Moore LV Coaggregation of Fusobacterium nucleatum, Selenomonas flueggei, Selenomonas infelix, Selenomonas noxia, and Selenomonas sputigena with strains from 11 genera of oral bacteria. Infect. Immun 57, 3194–3203 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]