Euarchontoglires (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Superorder of mammals

| EuarchontogliresTemporal range: Paleocene–Present PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N | |

|---|---|

|

|

| From top to bottom (left): rat, treeshrew, colugo; (right) hare, macaque with human. | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Magnorder: | Boreoeutheria |

| Superorder: | EuarchontogliresMurphy et al., 2001[1] |

| Subgroups | |

| †Apatemyidae? Gliriformes †Anagaloidea †Arctostylopidae?[2] Glires Euarchonta Primatomorpha Scandentia |

Euarchontoglires (from: Euarchonta ("true rulers") + Glires ("dormice")), synonymous with Supraprimates, is a clade and a superorder of placental mammals, the living members of which belong to one of the five following groups: rodents, lagomorphs, treeshrews, primates, and colugos.

Evolutionary affinities within mammals

[edit]

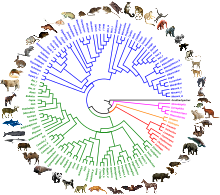

Phylogenetic position of Euarchontoglires (in blue) among placentals in a genus-level molecular phylogeny of 116 extant mammals inferred from the gene tree information of 14,509 coding DNA sequences.[3] The other major clades are colored: marsupials (magenta), xenarthrans (orange), afrotherians (red), and laurasiatherians (green).

The Euarchontoglires clade is based on DNA sequence analyses and retrotransposon markers that combine the clades Glires (Rodentia + Lagomorpha) and Euarchonta (Scandentia + Primates + Dermoptera).[1] It is usually discussed without a taxonomic rank but has been called a cohort, magnorder, or superorder. Relations among the four cohorts (Euarchontoglires, Xenarthra, Laurasiatheria, Afrotheria) and the identity of the placental root remain controversial.[4][5]

So far, few, if any, distinctive anatomical features have been recognized that support Euarchontoglires; nor does any strong evidence from anatomy support alternative hypotheses.[_citation needed_] Although both Euarchontoglires and diprotodont marsupials are documented to possess a vermiform appendix, this feature evolved as a result of convergent evolution.[6]

Euarchontoglires probably split from the Boreoeutheria magnorder about 85 to 95 million years ago, during the Cretaceous, and developed in the Laurasian island group that would later become Europe.[_citation needed_] This hypothesis is supported by molecular evidence; so far, the earliest known fossils date to the early Paleocene.[7] The combined clade of Euarchontoglires and Laurasiatheria is recognized as Boreoeutheria.[_citation needed_]

Phylogenetic relationships within the clade

[edit]

The hypothesized relationship among the Euarchontoglires is as follows:[8]

One study based on DNA analysis suggests that Scandentia and Primates are sister clades, but does not discuss the position of Dermoptera.[9] Although it is known that Scandentia is one of the most basal Euarchontoglires clades, the exact phylogenetic position is not yet considered resolved, and it may be a sister of Glires, Primatomorpha or Dermoptera or to all other Euarchontoglires.[10][5][11] Some old studies place Scandentia as sister of the Glires, invalidating Euarchonta.[12][13]

Whole-genome duplication may have taken place in the ancestral Euarchontoglires.[14]

- ^ a b Murphy, William J.; Eizirik, Eduardo; O'Brien, Stephen J.; Madsen, Ole; Scally, Mark; Douady, Christophe J.; Teeling, Emma; Ryder, Oliver A.; Stanhope, Michael J.; de Jong, Wilfried W.; Springer, Mark S. (2001). "Resolution of the early placental mammal radiation using Bayesian phylogenetics". Science. 294 (5550): 2348–2351. Bibcode:2001Sci...294.2348M. doi:10.1126/science.1067179. PMID 11743200. S2CID 34367609.

- ^ Missiaen P, Smith T, Guo DY, Bloch JI, Gingerich PD (2006). "Asian gliriform origin for arctostylopid mammals". Naturwissenschaften. 93 (8): 407–411. Bibcode:2006NW.....93..407M. doi:10.1007/s00114-006-0122-1. hdl:1854/LU-353125. PMID 16865388. S2CID 23315598.

- ^ Scornavacca C, Belkhir K, Lopez J, Dernat R, Delsuc F, Douzery EJ, Ranwez V (April 2019). "OrthoMaM v10: Scaling-up orthologous coding sequence and exon alignments with more than one hundred mammalian genomes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 36 (4): 861–862. doi:10.1093/molbev/msz015. PMC 6445298. PMID 30698751.

- ^ Asher, RJ; Bennett, N; Lehmann, T (2009). "The new framework for understanding placental mammal evolution". BioEssays. 31 (8): 853–864. doi:10.1002/bies.200900053. PMID 19582725.

- ^ a b Kumar, Vikas; Hallström, Björn M.; Janke, Axel (2013-04-01). "Coalescent-Based Genome Analyses Resolve the Early Branches of the Euarchontoglires". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e60019. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...860019K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060019. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3613385. PMID 23560065.

- ^ Smith, H. F.; Fisher, R. E.; Everett, M. L.; Thomas, A. D.; Randal-Bollinger, R.; Parker, W. (October 2009). "Comparative anatomy and phylogenetic distribution of the mammalian cecal appendix". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 22 (10): 1984–1999. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01809.x. PMID 19678866.

- ^ O'Leary, M. A.; Bloch, J. I.; Flynn, J. J.; Gaudin, T. J.; Giallombardo, A.; Giannini, N. P.; Cirranello, A. L. (2013). "The placental mammal ancestor and the post–K-Pg radiation of placentals". Science. 339 (6120): 662–667. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..662O. doi:10.1126/science.1229237. hdl:11336/7302. PMID 23393258. S2CID 206544776.

- ^ Esselstyn, Jacob A.; Oliveros, Carl H.; Swanson, Mark T.; Faircloth, Brant C. (2017-08-26). "Investigating Difficult Nodes in the Placental Mammal Tree with Expanded Taxon Sampling and Thousands of Ultraconserved Elements". Genome Biology and Evolution. 9 (9): 2308–2321. doi:10.1093/gbe/evx168. PMC 5604124. PMID 28934378.

- ^ Song S, Liu L, Edwards SV, Wu S (2012). "Resolving conflict in eutherian mammal phylogeny using phylogenomics and the multispecies coalescent model". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (37): 14942–7. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10914942S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211733109. PMC 3443116. PMID 22930817.

- ^ Foley, Nicole M.; Springer, Mark S.; Teeling, Emma C. (2016-07-19). "Mammal madness: Is the mammal tree of life not yet resolved?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 371 (1699): 20150140. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0140. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 4920340. PMID 27325836.

- ^ Zhou, Xuming; Sun, Fengming; Xu, Shixia; Yang, Guang; Li, Ming (2015-03-01). "The position of tree shrews in the mammalian tree: Comparing multi-gene analyses with phylogenomic results leaves monophyly of Euarchonta doubtful". Integrative Zoology. 10 (2): 186–198. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12116. ISSN 1749-4877. PMID 25311886.

- ^ Meredith, Robert W.; Janečka, Jan E.; Gatesy, John; Ryder, Oliver A.; Fisher, Colleen A.; Teeling, Emma C.; Goodbla, Alisha; Eizirik, Eduardo; Simão, Taiz L. L. (2011-10-28). "Impacts of the Cretaceous terrestrial revolution and KPg extinction on mammal diversification". Science. 334 (6055): 521–524. Bibcode:2011Sci...334..521M. doi:10.1126/science.1211028. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 21940861. S2CID 38120449.

- ^ Zhou, Xuming; Sun, Fengming; Xu, Shixia; Yang, Guang; Li, Ming (2015-03-01). "The position of tree shrews in the mammalian tree: Comparing multi-gene analyses with phylogenomic results leaves monophyly of Euarchonta doubtful". Integrative Zoology. 10 (2): 186–198. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12116. ISSN 1749-4877. PMID 25311886.

- ^ Dehal, Paramvir; Boore, Jeffrey L. (2005-09-06). "Two Rounds of Whole Genome Duplication in the Ancestral Vertebrate". PLOS Biology. 3 (10): e314. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030314. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 1197285. PMID 16128622.

- Churakov, G.; Kriegs, J. O.; Baertsch, R.; Zemann, A.; Brosius, J. R.; Schmitz, J. R. (2009). "Mosaic retroposon insertion patterns in placental mammals". Genome Research. 19 (5): 868–875. doi:10.1101/gr.090647.108. PMC 2675975. PMID 19261842.

- Goloboff, Pablo A.; Catalano, Santiago A.; Mirande, J. Marcos; Szumik, Claudia A.; Arias, J. Salvador; Källersjö, Mari; Farris, James S. (2009). "Phylogenetic analysis of 73 060 taxa corroborates major eukaryotic groups". Cladistics. 25 (3): 211–230. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2009.00255.x. hdl:11336/78055. PMID 34879616.

- Nikolaev, Sergey; Montoya-Burgos, Juan I.; Margulies, Elliott H.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program; Rougemont, Jacques; Nyffeler, Bruno; Antonarakis, Stylianos E. (2007). "Early History of Mammals is Elucidated with the ENCODE Multiple Species Sequencing Data". PLoS Genetics. 3 (1): e2. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030002. PMC 1761045. PMID 17206863.

- Springer, Mark S.; Murphy, William J.; Eizirik, Eduardo; O'Brien, Stephen J. (2003). "Placental mammal diversification and the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (3): 1056–1061. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.1056S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0334222100. PMC 298725. PMID 12552136.

- Waddell, Peter J.; Kishino, Hirohisa; Ota, Rissa (2001). "A phylogenetic foundation for comparative mammalian genomics". Genome Informatics. 12: 141–154. PMID 11791233. Archived from the original on 2019-07-10. Retrieved 2015-08-27.

- Wildman, Derek E.; Chen, Caoyi; Erez, Offer; Grossman, Lawrence I.; Goodman, Morris; Romero, Roberto (2006). "Evolution of the mammalian placenta revealed by phylogenetic analysis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (9): 3203–3208. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.3203W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0511344103. PMC 1413940. PMID 16492730.