Robert Beaser Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

Composer Robert Beaser

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Robert Beaser has emerged as one of the most accomplished creative musicians of his generation. Since 1982, when The New York Times wrote that he possessed a “lyrical gift comparable to that of the late Samuel Barber,” his music has won international acclaim for its balance between dramatic sweep and architectural clarity. The Baltimore Sun writes “Beaser is one of this country’s huge composing talents, with a gift for vocal writing that is perhaps unequaled.” His opera The Food of Love, with a libretto by Terrence McNally, is part of the Central Park trilogy, which opened to worldwide critical accolades at Glimmerglass and New York City Opera. Televised nationally on PBS Great Performances, it received an Emmy nomination in 2000.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts on May 29, 1954, Beaser was brought up in a non-musical family. His father was a physician and mother was a chemist. He grew up in Newton, Massachusetts where he distinguished himself at a young age as a percussionist, composer and conductor. He made his debut with the Greater Boston Youth Symphony at Jordon Hall when he was 16, conducting the premiere of his own orchestral work, Antigone. He went on to study with Yehudi Wyner and Jacob Druckman at Yale College, graduating summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa in 1976, and later received his Master of Music, M.M.A. and Doctor of Musical Arts degrees from the Yale School of Music. He studied conducting with Otto-Werner Mueller and William Steinberg. Other teachers included Tōru Takemitsu, Arnold Franchetti, Goffredo Petrassi and Earle Brown. He studied with Betsy Jolas on a fellowship at Tanglewood. In 1977 he became the youngest composer to win the Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome. Residence in Rome proved a watershed in his development, and he embraced more tonal language, synthesizing a variety of diverse influences from jazz to folk into his writing.

From 1978-1990 he served as co-Music Director and Conductor of the chamber ensemble Musical Elements at the 92nd Street Y, bringing premieres of over two hundred works to Manhattan. From 1988-1993 he was the Meet the Composer/Composer-in-Residence with the American Composers Orchestra at Carnegie Hall, and served as the ACO’s artistic advisor until January 2001, when he assumed the role of Artistic Director. Since 1993, he has been Professor and Chairman of the Composition Department at the Juilliard School in New York.

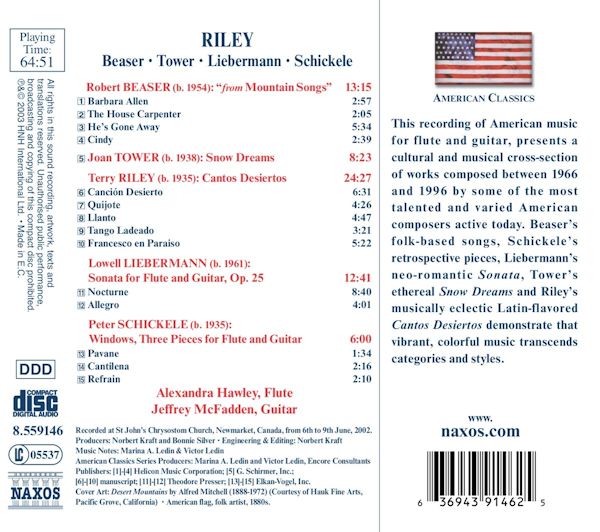

Beaser’s compositions have earned him numerous awards and honors. In 1977 he became the youngest composer to win the Prix de Rome from the American Academy in Rome. In 1986, Beaser’s widely heard Mountain Songs was nominated for a Grammy Award in the category of Best Contemporary Composition. He has received fellowships from the Guggenheim and Fulbright Foundations, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Goddard Lieberson Fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Charles Ives Scholarship, an ASCAP Composers Award, a Nonesuch Commission Award, and a Barlow Commission. In 1995 the American Academy of Arts and Letters honored him with their lifetime achievement award, the Academy Award in music.

Beaser has received major commissions from the New York Philharmonic (150th Anniversary Commission), the Chicago Symphony (Centennial Commission), the Saint Louis Symphony, The American Composers Orchestra, The Baltimore Symphony and Dawn Upshaw, The Minnesota Orchestra, Chanticleer, New York City Opera, Glimmerglass, and WNET/Great Performances among others. Recent major orchestral performances have come from the Chicago, Saint Louis and Baltimore Symphonies, The Minnesota Orchestra, The New York Philharmonic, the American Composers Orchestra, the Vienna Radio Orchestra, the Dutch Radio Symphony and the Hong Kong Philharmonic with James Galway. His music has been performed, recorded and commissioned by artists such as Leonard Slatkin, Richard Stoltzman, Eliot Fisk, James Galway, Lauren Flanigan, Dawn Upshaw, David Zinman, Dennis Russell Davies,Renée Fleming, Lukas Foss, José Serebrier, Paul Sperry, Stewart Robertson, and Big Bird.

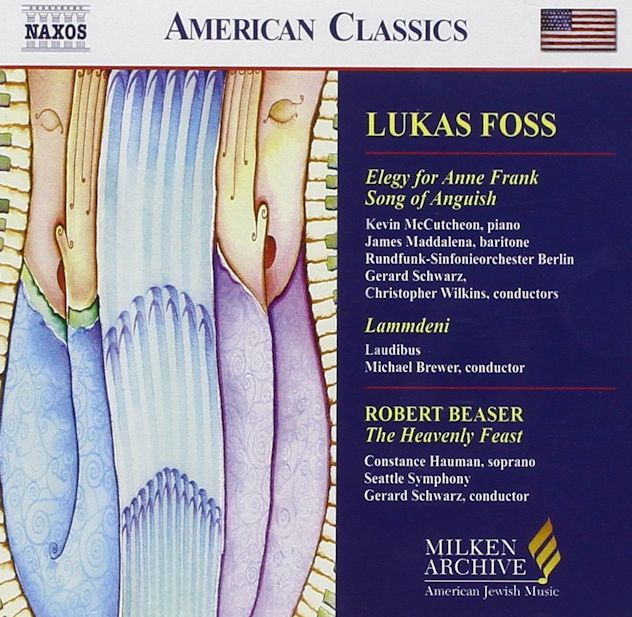

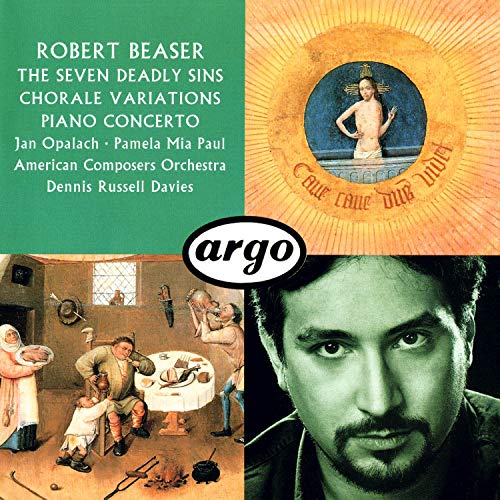

His principal recorded works include The Seven Deadly Sins,Chorale Variations, and Piano Concerto (London/Argo), The Heavenly Feast (Milken Archives), Song of the Bells (New World Records), Notes on a Southern Sky (EMI-Electrola), Mountain Songs (Musicmasters, Koch, Gajo, Siemens, HM Records Venezuela), and Landscape With Bells (Innova).

== Biography taken from the website of the American Composers Orchestra, as well as other sources.

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

In January of 1991, Robert Beaser was in the Windy City for the world premiere of Double Chorus with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. It is, or was at that time, very unusual for a thirty-six-year-old composer to have a work played by that ensemble, to say nothing of a world premiere. The concert also held a recent work by another young composer, H

’ un [Lacerations] by Bright Sheng, as well as the Saint-Saëns Violin Concerto #3, and the complete Mother Goose, all conducted by Kenneth Jean.

Beaser agreed to meet with me after the second of four performances, and we dove right in to the discussion . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: What is extra special about writing a piece for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra?

Bruce Duffie: What is extra special about writing a piece for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra?

Robert Beaser: [Enthusiastically] The Orchestra!

BD: Really?

RB: Of course!

BD: Is the Chicago Symphony a lot better than the others, or just a little better than the others? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, see my interview with Gerard Schwarz.]

RB: All of the great orchestras have strengths and weaknesses. The Chicago Symphony doesn’t seem to have too many weaknesses, and it has a number of great strengths. Clearly, the great brass section lives up to its legendary reputation, but also the pride and intensity which they bring to their work, and to the music-making in general, is something which a lot of other orchestras could learn from. I don’t want to mention any cities, but it’s definitely something that is a great inspiration to see. I have had no experience with Chicago live, only on recordings, but live you see it. In the recordings you just hear it, but live you also see it.

BD: What is it that makes a great orchestra great?

RB: It has to do with their ability. First of all, they’re really to project a personality which is their own. That can be said about art, as well. Art which is really, really outstanding projects some sort of personality, and an orchestra has its own personality. That means a cohesiveness and an ability, first of all, to understand the stylistic difference clearly. But beyond that, to be able to play with a sense of ensemble that seems almost effortless and natural, and Chicago does that. There’s an effortlessness to the way they mesh together, and that’s wonderful.

BD: When you were writing for them, did you write with this in mind?

RB: Every time I write a piece, I’m thinking of the person or ensemble that I’m writing for. It’s really important. I’ve been very lucky over the last ten years because I’ve been able to write for some wonderful performers and ensembles. Each time, I’m very cognizant of what image that particular performer or ensemble reflects to me. With Chicago, I was somewhat intimidated by just the fact of the power of the orchestra. The Chicago Symphony as an intensely powerful orchestra.

BD: But when you write for Chicago, does prelude it being done by Cleveland, or Saint Louis, or perhaps Ken Jean’s other orchestra, the Florida Philharmonic?

RB: [Laughs] Goodness, gracious, I hope not! I would love it to be done by those other orchestras, and I’d love to see the other personalities, but the fact is when I was writing this piece, I really has Chicago in mind. One of the reasons that I wrote Double Chorus the way I wrote it was because I was trying initially to figure out a way to get the brass section to sound the way I wanted them to sound. I had an image of the way I wanted the brass to sound, and in order to do that I had to use

‘block’ brass writing, which was something entirely new of me. I hadn’t really done much. The only time I’d done this sort of ‘block’ writing was in choral pieces.

BD: So before that, it was all linear?

RB: Yes, it tends to be more contrapuntal, more linear. The

‘block’ writing is where harmonically all the instruments line up. It makes such a wonderful brass sound, of course, and it’s something which had not been in the orchestral music that I’d been writing. I just never had any opportunity to use it, but with Chicago, I knew I had to. So, with that in mind, I began to develop material which had that property, and could lend itself to that sort of writing. As a result, I have a piece where I can really let the brass sing at the end, which is something that I was dying to do.

BD: And of course, you utilized the percussion, too!

RB: That’s always something which I utilize. I love to use percussion. I’m a former percussionist, so I’m a little bit biased...

BD: Do you have to bend over backwards to make sure your string writing is idiomatic because you’re a percussionist?

RB: It’s interesting... Some people ask me how I can write for the strings or woodwinds if I don’t play them. I’m a pianist and percussionist, so if you went under that rubric I would only write for piano and percussion. It’s an instinctual thing for a composer, and some composers have a natural way. Britten comes to mind as a composer who’s really naturally wonderful at adapting for each instrument, and finding a line which says he wants to be with that instrument. I would like to think that I have a little bit of that gift, and I’ve been working very hard to really understand what makes each individual instrument tick. So, every time I write an orchestra piece, I make sure I can sing every line. Every one has to sing and make sense to me, and that means to sing in the context of the clarinet, or the tuba, or the contra-bassoon, or the viola. Each instrument has a different quality, and I want to use that. BD: Once you have your musical line, do you then add the musical color of each instrument?

BD: Once you have your musical line, do you then add the musical color of each instrument?

RB: Yes. The process of orchestrating a piece is that you start with your sketches. Then, I work in a shortscore form, which means there are basically two lines.

BD: [Surprised] Is it more than just a piano reduction?

RB: It’s more than a piano reduction. A short-score is not usually just two lines, but probably four to six lines.

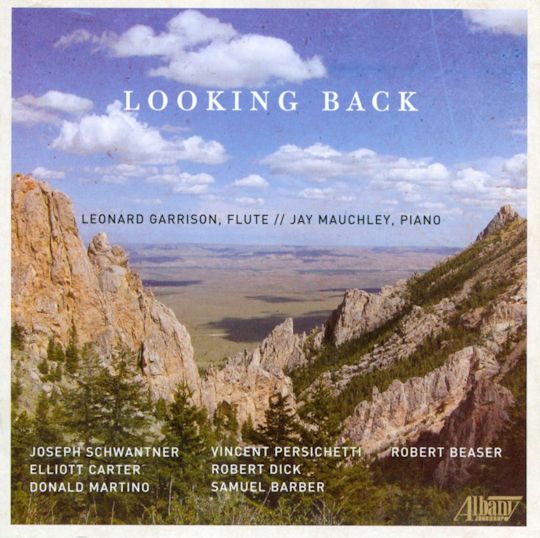

BD: I always thought that short-scores were usually six lines. [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my interviews with Joseph Schwantner,Elliott Carter,Donald Martino, andVincent Persichetti.]

RB: Yes, although I cram a lot into four lines. The orchestration then comes as a blowing up of that, but without the essential material. I always think of orchestration as a function of the line. Orchestration, for me, is not fooling around with colors and hoping that the colors can add up to the line. Rather, there’s got to be an internal line that goes through the piece that I know musically, and that has to do with notes, and pitches, and harmony, and all of that good stuff which we all know and love.

BD: When you’re making the short-score, do you sometimes get ideas and jot notes to yourself that this has to be here and that has to be for somebody else?

RB: You mean instrumentational?

BD: Yes, or even other ideas.

RB: Generally speaking, when I make the short-score I very often will know, for example, that this section, which opens the piece, will be a brass chorale, or this other section will be a heterogeneous thing. I’ll write a line, and I’ll understand immediately. You see the line, and you know it’s got to be an English horn. It’s just got to be. Other things are more difficult. Sometimes, when you have a big tutti section, you spend a lot of time parsing out the divisions with the orchestra. Very often what I’ll do is set one line, which is the essential line, and then add another layer of coloring. Then the third layer will be the percussion. I know the percussion has to serve a certain function there, but I’m not exactly sure how it’s going to work. So, the percussion in the piece always comes last for me. I lay the percussion in because percussion, for me, is very structural. If you use a big crash cymbal once at the end of a piece, you can’t be using it five times before, because that particular crash cymbal has to have a meaning. So if you’ve blown all of your crash symbols early on in the piece, it’s not going to have that meaning. Actually, that’s the principle of orchestration, as well. When you orchestrate a section, you’ve got to prepare. If the horns are going to enter, the horns cannot be playing prior to their entry. It’s natural.

BD: When you’re doing the orchestration, do you ever change some of the ideas that are actually there in the linear or the chordal progressions?

RB: There are moderate changes. There are modifications in many places. You can add notes, and very often range or the register has something to do with it. Doubling in orchestras is very tricky. You have to decide how you want to double something, and very often you’ll take out the middle and space it out up on top and bottom. Or, if you have a simple line in the lower part of the soprano clef, you have to decide if you want to double it two octaves above or one octave above. These are all wonderful options that you have, and it has to do with weights and balances. It’s all the alchemy of orchestration.

BD: But this all comes after you’ve essentially got the shape of the piece, and the direction of the piece on paper?

RB: Yes, it does. Now that doesn’t mean that for every piece I have a full short-score from beginning to end before I orchestrate. In this particular piece I was stretched for time, and I had a short-score of the first half, and started orchestrating that. Then I started making a little short-score of the whole last section, but essentially you’re correct. I don’t go on. If I’ve orchestrated to page forty-three, and I’ve got to get to page fifty-four, there’s got to be a short-score before I can continue. I won’t just go and lay it onto the orchestra without the short-score.

BD: We’re progressing backwards through the compositional process... RB: Right, exactly.

RB: Right, exactly.

BD: Going back one more step, when you’re getting ideas and you’re putting notes down on paper, are you always in control of the pencil, or are there times when you find that pencil is somehow controlling your hand?

RB: That is what you look for. You try very hard to get to the point where the pencil is controlling you. For me, it takes an awfully long time. I spend an awful lot of time feeling like I’m wasting time. I go to the piano or the desk every morning, and I sit and I work with material, and I don’t like it, and it doesn’t make sense, and I don’t know what I’m doing. At a certain point in the piece I get little revelations, and gradually the revelations get closer and closer together. I guess it

’s like labor. [Laughs] I would not know about that, but it happens with every single piece I’ve written, that at some point in the piece it’s as if the curtain opens and finally I’m on stage. Before, I was knocking on the door, and at the point where the curtain opens, and I’m on stage, and I really feel like I’ve got control of this piece. Before that happens, the piece has control of me, because I don’t know where I am. It’s bigger than me; it seems unwieldy; it seems like it’s beyond my grasp, and at a certain point everything becomes really easy. It’s like all the decisions become obvious. I know exactly where I’m going, and all of the decisions somehow make themselves. In the span of compositional process, that very often can happen two-thirds of the way through the piece, and that first two-thirds can be utter struggle.BD: Then do you go back and tinker with the first two-thirds, or do you find that they’ve been right?

RB: Yes, but you’re also presupposing that I write the piece from beginning to end, which is not always the case. In this particular piece I did write from beginning to end, but in many pieces I start in the middle.

BD: You get a good idea and you’ll know it’ll go in the middle, so you write it, and then something else goes before and after?

RB: Exactly! For example, for my Piano Concerto, which was done in St. Louis in May of 1990, I spent three months easily developing material, and I didn’t know where that material would go. I just knew that this was Piano Concerto material, and the ideas all related to each other. It was related to material that I had, and I would pare down and pare down, and at some point I would make a decision that this is second movement material, and this is third movement material, and this is first movement material.

BD: Was some of it trash-can material?

RB: Oh, a lot of it was trash-can material! I have a division between trash-can material and other-piece material. Very often when I’m going to start a new piece, I’ll go back to the sketches that have been saved from the trash-can. They are on the back edge of my piano, and I’ll look at that material first to see if there’s anything which will either stimulate my mind or that I can use. Sometimes I find it, and sometimes I don’t, but it gets my mind going.

BD: It might be an idea that’s still gnawing at you, and you want to develop it?

RB: Exactly, because you know they are certainly good ideas. For me, the process of composition is getting it from your head onto the page. It can be a terrific idea, and that’s all well and good, but if it’s in my head, then it’s not on the page. That doesn’t work, so I’ve got to get that idea down on the page. Once it’s on the page, it can really go in any number of places, and I really don’t know what I’m going to use it for. Free-association comes into the compositional process, and it occurs with something that’s on the page, sitting and collecting dust off to the side of your piano. You’re working on a bit of material in the second movement, and all of a sudden that thing that was on the page becomes an incredibly relevant issue for what you’re dealing with right then. I’m working on a new piece and I see how it relates, and I realize this is going to work just fine.

BD: Is that when you feel like you’ve really arrived with something?

BD: Is that when you feel like you’ve really arrived with something?

RB: Yes, those are points of arrival, and those are points where little light bulbs go off in your head and you realize that’s what you want.

BD: Do you only work on one piece at a time, or do you have a couple going?

RB: I’m not the type of composer that can work on a number of pieces. Many of my colleagues can, but I simply am not able to.

BD: The way you’ve been talking, it seems like all of your effort is concentrated on one piece. [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my interviews with Joan Tower, Lowell Liebermann, and Peter Schickele.]

RB: I like to do the total-immersion method, because for me, each piece that I go into is really a world, and has its own rules and its own order. If I’m stepping outside of that world to work on another piece, my brain is not going to be able to function properly because I’m going to feel like I’m dividing myself too much.

BD: Do you ever have one of these ideas that you know won’t work, so you set it aside and know it’ll work in another piece?

RB: Absolutely!

BD: Does it ever keep gnawing at you to where you think you’d better work on that other piece?

RB: Especially at the beginning of a piece, I always want to be doing something else. Every time I start a piece, I’m never happy with anything, and I’m always more interested in writing another piece. Woody Allen had a phrase about always wanting to be somewhere else. [Both laugh]

BD: We keep going backwards in the compositional process... I trust you get a whole pile of commissions, so how do you decide which commissions you’ll accept and which commissions you’ll turn aside? Obviously, when Chicago Symphony knocks at your door, you will say yes...

RB: I did say yes, and as a matter of fact, I was very fortunate because they wanted me to do the piece that I wrote for this season, for last season, but I had prior commitments

— that Piano Concerto being one of them. They were very kind to let me do it in this season. Otherwise, I would have had to say no, because literally it was a situation where I had a hard and fast commitment. Sometimes, if something wonderful comes up and you literally physically can’t do it, you have to say you can’t do it. I would have been terribly disappointed had that happened, and luckily it didn’t. But generally speaking, you try to leave enough time for yourself between commissions, and that’s a very, very tricky business because you’ve no control over what’s going to happen, and who’s going to come and ask you. Very often they come in spurts, so you get a lot of people asking you at one time. Then you have to say you’ve got all this other stuff. Then you have a period of time when nobody’s asking you, and you wish that you had some of those other things. [Laughs]

BD: If you get a whole pile of offers all at once, how do you decide which ones you will say you will do, and others you’ll either postpone or turn aside?

RB: What’s really essential for a composer

— and what’s essential for people to know about composers — is that composers are not machines that can crank out music. They don’t just wake up in the morning and crank out some more music like spinning out wallpaper. I don’t think even Vivaldi did that, even though he was clearly derided for that. What you have to do, as a composer, is make sure that you are growing somehow with each piece. Each piece represents something that will be a bit of an adventure, and a little bit different from what you’ve done before. I’ve written a lot for the flute, and if somebody comes up to me now and wants me to write some more for the flute, I would have to say that I just have nothing more to say for the flute right now. They’ll have to wait ten years, or whatever, because I feel I’m written out. You really try to vary your output. You try to get things lined up in a row that will offer you variety, otherwise you’re going to go crazy writing the piece. You don’t want to write the piece that you just finished over and over again. You’re not satisfied.

BD: Do you ever go back and revise scores?

RB: [Thinks a moment] Yes, a little bit, but I’m not a reviser as a I know some people are. I’m so compulsive about my own scores that by the time they get out to be played, they’ve usually been poured over to the point where I’m pretty happy with them. There’s always little stuff that you feel doesn’t quite work, and you can adjust that, but it’s generally little stuff. I can’t remember when I let a piece out and wish I’d added another section in the middle. It’s mostly orchestrational and technical details that we’re talking about for revision.

BD: When you’re working on it, and you’re getting it just the way you want it, how do you know when to put the pencil down and say that it’s ready?

RB: A piece has a natural architecture, and you, as a composer, are always aware of that. As a composer, or as anybody who’s working on a large creative project, you have to be aware of the foreground, the middle-ground, and the background of what you’re doing. While you’re working out the little details of the foreground, you’ve always got to constantly be keeping an eye on the larger shape of the piece. You know this instinctively, or you had better know this instinctively! Some people don’t know this instinctively, and that’s why there are many cuts, because they tend to go on, and on, and on. But one of the things you have to try to know instinctually is how long this amount of music should naturally take. You don’t want to say any more, and you don’t want to keep repeating something if it doesn’t need to be repeated. It’s very important to understand that. How do you know? You just know. It’s an instinct. You develop an instinct for it. It’s just the same way you know that you have to put a C# in that measure and not a C natural. The note-decisions that you make, and the orchestrational-decisions you make, and the decisions you make when the piece is finished are all the same sort of decision. It’s an instinct, but each time you’re dealing with different aspects of the piece. In one, you’re dealing with a full architectural picture, so you’re standing back. In another, you’re dealing with molding the side of the building, so you’re just putting a little bit of a shape onto it.

BD: Then, when you hand over the ‘building’, how much of the conductor’s job is ‘furnishing’ the insides of the ‘building’, and maybe putting a new coat of paint on the wall?

RB: The main thing is that you have to give him the key to the door to get inside the building. That key, of course, is the musical value and the substance of the piece. It’s wonderful how every conductor can put their own stamp, and their own personality, and it’s very important for them to do so. Of course, when the conductor’s personality interferes with what the composer really means, then it becomes a problem, so conductors have to be careful. Whether the composer’s dead or alive, conductors are treading a very fine line trying to serve what is on the page. That can be very, very tricky because what’s on the page presents this notion of the composer’s manuscript as the absolute Bible; that every single word and every single marking the composer put down has got to be obeyed with the utmost of literalness. That’s a little wrong because most of the composers that I know change their minds a lot.

RB: The main thing is that you have to give him the key to the door to get inside the building. That key, of course, is the musical value and the substance of the piece. It’s wonderful how every conductor can put their own stamp, and their own personality, and it’s very important for them to do so. Of course, when the conductor’s personality interferes with what the composer really means, then it becomes a problem, so conductors have to be careful. Whether the composer’s dead or alive, conductors are treading a very fine line trying to serve what is on the page. That can be very, very tricky because what’s on the page presents this notion of the composer’s manuscript as the absolute Bible; that every single word and every single marking the composer put down has got to be obeyed with the utmost of literalness. That’s a little wrong because most of the composers that I know change their minds a lot.

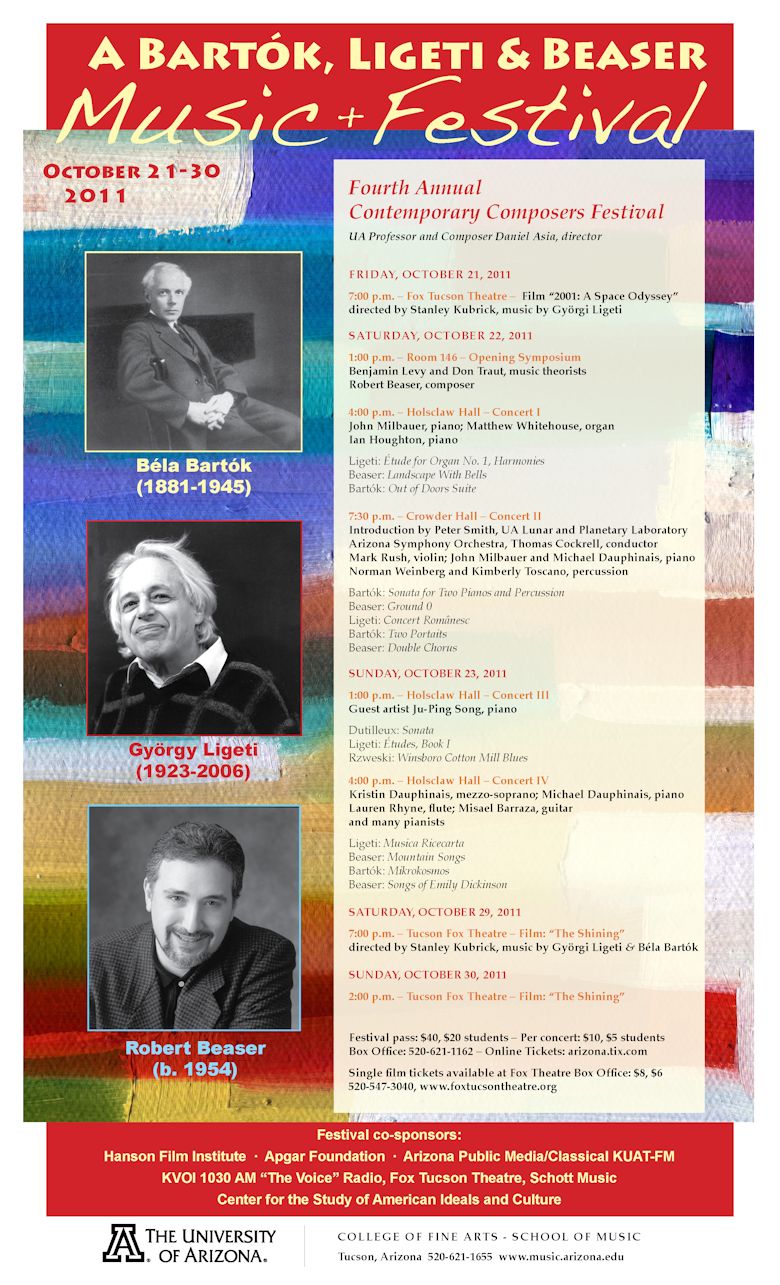

BD: Do you also expect that the score will be brought alive, and not just played as pitch and duration? [Vis-à-vis the poster shown at left, see my interview with Frederic Rzewski. (This is the correct spelling, btw.)]

RB: Yes. Musical notation, as we all know, is really lacking in terms of being exact. It’s really incapable of being so precise that it can tell you all of the information you need to make music happen. There is something that is absolutely magical, and wonderful, and is necessary that one has to add in order to make that music happen. But there can be many, many different personalities that can be injected into it. It’s not just one personality; there are many right ways to do something, and that’s why, when people come along and they say that they have the key to Baroque music, that they understand, that they’ve got the phone number of this composer, I run the other way! I find that to be pretentious and basically, as a composer, I know intuitively that it’s wrong.

BD: Would those performers ill-serve contemporary as well as Baroque music?

RB: Normally, people who specialize in Baroque music don’t do contemporary music, so I can’t answer that. [Both laugh]

BD: Without naming names, are there some conductors who do contemporary music who should stay far away from it?

RB: There probably are, but most examples that I can think of are composers who conduct. That’s a terrible problem. As a composer who conducts, I speak from experience. I happen to be a trained conductor, and somebody who can actually conduct, and has conducted, so I get very upset when composers go on the podium and think that they can conduct because they’ve composed a work.

BD: Because you are a trained conductor, does that make you a better composer, or at least a better technician in scoring and writing out your ideas, and getting them so that another conductor will understand exactly what you mean?

RB: It certainly helps. What also helps is having experience with an orchestra. I grew up with an orchestra. I played in orchestras. Orchestras are in my blood. Other composers grew up with other sorts of music. A lot of composers of my generation grew up with Rock music, for example, and alternative types of music, so they find it very difficult to get into the guts of the orchestra and really understand it. Because I’ve been a conductor, and because I understand what makes an orchestra tick, it seems to me that I can figure out pragmatically what’s going to work and what isn’t going to work. There is a real pragmatic component to being a composer. You have to understand the limitations of the orchestra. Limitations are wonderful. People always say that the orchestra can’t do this and can’t do that, but the fact of the matter is that it can do just about anything. But it can’t do everything, and you have to understand where to draw the line, and you have to understand where to make the orchestra sound the way it wants to sound. The orchestra is an instrument just like a piano is an instrument. You want to make the piano sound the way it wants to sound, just as you want to make the violin sound. You want to make the orchestra sound the way it wants to sound. There are many different ways to do that, of course, and there are many different sounds that it wants to make, but there are also a number of sounds that it doesn’t want to make, and I can always tell a composer whose ears are tuned to that. It crosses stylistic boundaries. It has nothing to do with tonal, or atonal, or this, or that. It has to do with the composer having an ear for the orchestra, and an understanding of the instruments, and how the instruments combine sonically, timbrely, and how they add up. You can hear instantly.

BD: Is this what separates great music from lesser music, by a composer who understands these things?

RB: I’m not sure I’d use the words ‘great’ or ‘lesser’. I would say that for me, first and foremost, music has to be clear. It has to be well-heard. You’ve got understand that there is an ear at work here. There are a number of composers who became very fashionable by writing ‘concept pieces’. These are pieces that had wonderful ideas behind them, by composers who were very ingenious and very smart. But very often the composers lacked the essential ear, that basic ear to be able to distinguish between the sounds that the instruments or the orchestras want to make, and the sounds that they don’t want to make.

BD: Were they also shutting out the audience in all of this?

RB: The natural result of that, of course, was to shut out the audience, because the audiences became unsatisfied.

BD: Do you take the audience into account when you’re writing all those notes on the page?

RB: I take communicating into account, and, of course, communicating presupposes an audience. I don’t actually think of an audience sitting out there, but I do think of how I want the orchestra to sound. I think of myself as the audience, and I think how I would like to hear it sound, and I want it to sound as clear as possible. I want it to be coherent. I want to make a message in my music that people can understand. It doesn’t mean that it’s the same message for every person, but I believe my music has a very strong narrative component. I’m using a literary term to define music, but

‘narrative’ is something which has to do with an abstract painting versus a representational painting, and music is always inherently abstract. But within the abstraction, there is a way of telling a story by logically following natural psychological patterns and identities. It’s very important to establish identities in music, because if you can hear something that you can hang your hat on, then you can hear when it changes. If you can’t hear and identify a part of a musical score, all the changes and variations you want to make are irrelevant. You can say that you’re writing ‘variations for orchestra’, but if aurally nobody can identify the material in the first place, or it takes the hundredth hearing to identify the material, it’s going to be very difficult to get anybody to listen to new music.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You mean it would be an oxymoron to write a set of variations on a non-existent tune?

RB: [Laughs] Many people say Schoenberg did that, but I love Schoenberg’s tunes. Still, Schoenberg had a bit of a problem mostly because his tunes generally were harder to hum than most. Some of his followers had a big problem because they got more and more abstract, to the point where the material they were using was so obscure that they would claim to make a variation on it, but you didn’t know they were variating!

BD: Almost like an in-joke just for other knowledgeable people?

RB: Sure, and that’s what’s happened during the generation after the War.

BD: Are you particularly proud of the fact that you’re a tonal composer, and now the world seems to be coming back to tonality?

RB: Yes. When I was at Yale in the

’70s I felt a bit out of step. I felt that nobody was paying much attention to music that I loved. I remember talking to a lot of my colleagues at the time who were my age, and they weren’t writing tonal music. But they were feeling as though they needed to make a change, and the change happened really in the late ’70s. I feel very good because I’m very, very lucky to have been born at this time, and not twenty years earlier, because twenty years earlier, I could have been writing this music and nobody would have paid any attention to it. So, I’m very fortunate that we’ve seen a breakdown of these ideological ways of looking at music, and discussing it. The whole Modernist monkey which was on our back for so long has been broken down. Of course, just like when the wall came down in Berlin, and we think we’re going to have a thousand years of peace, we get lots of different wars immediately after. So, when you break down the hegemony of Serial music that was held over modern music for so many years, you have a sort of a chaos, which is what’s going on now. There’s a lot of chaos stylistically, and that leaves room for some problems as well. Quality goes down, and people’s ideas of what is really good and what’s not tend to get watered down somewhat. People tend to get a little commercial in their outlook.

BD: Does it worry you at all that a couple of hundred years from now, just as we lump Corelli and Torelli and a lot of those composers together, that people will be lumping Milton Babbitt and Philip Glass together as one kind of style?

RB: I can’t imagine it they would lump Philip Glass and Milton Babbitt together. If they did, they would have to have their ears re-tuned. The Twentieth Century style may be known for its diversity, and maybe that’s what they’ll be lumping together. Hopefully, the late Twentieth Century style will be known for the co-existence of many, many varieties of music, and it’s enormously exciting because of that.

BD: Let me ask the big question. What is the purpose of music in society?

BD: Let me ask the big question. What is the purpose of music in society?

RB: That’s a very, very difficult question. You should ask that of a music historian or a critic.

BD: I do, but right now I’m asking you because you’re a composer who is doing it.

RB: I’m not dodging the question except in one sense. Artists, as defined by Plato, have a bit of a privilege of being myopic. Artists do not have to be philosophers, so there is a real dichotomy there. One of the great things about being an artist is that we see the world a little bit differently, according to our own way, and that presupposes a bit of... I don’t want to say a lack of understanding, but there are blocks that artists have in being able to see the big picture. That’s entirely necessary, sometimes, to be able to be inward-looking, and to be able to pull out from the inside of your soul the things that have meaning to you. So, as to the purpose of music in society, I’m very troubled by a lot of what I see. I see a lot of commercialization of music. Even in the popular music’s sphere, I find the quality has deteriorated enormously in terms of the truthfulness of the utterance. There’s a lot of cynicism and manipulation that goes with commercial music, and that is inevitable when the market place enters into it. But you see that, as well, in the field that I’m in, which is Contemporary Classical Music. You will see that, but that’s healthy any time you have a market place, and you certainly had a market place for opera. Look back in the late Nineteenth century, and you see some of the more commercial composers, who have gone by the wayside, and you see some of the composers who stuck to their guns. They’re the ones who lasted. In any milieu where’s there’s a healthy competitiveness going on, you’re going to be beset by many, many different co-existing brands of art, and it’s going to be very hard to tell what’s good and what’s not good while you’re living it. It sorts itself out over time, and a lot has to do with performers wanting to perform a work over and over again. The performers play a great role there because performers are smart. They tend to go for the good stuff, but this takes time. In the meantime, it seems like a very confusing world out there.

BD: Are you optimistic about it at all?

RB: Oh, sure, I’m optimistic in the sense that in many ways there’s more interesting contemporary classical music being written today than there has been in years. We’re living in a very, very wonderful age. I’m very, very happy with what I see at the ACO [American Composers Orchestra], where I am the composer-in-residence. I see a number of young composers who are really quite brilliant and interesting, and have their own voices.

BD: Do you do some teaching?

RB: I have not taught since the early

’80s. I’ve been very fortunate not to have had to do that. [_As noted in the biography at the top of this webpage, he would become Professor, and Chairman of the Composition Department at Juilliard in 1993, two years after this interview took place._]

BD: Do you have any advice for other composers?

RB: The best thing that a composer can do is not look around him, but look inside. So many composers look around and they see well who’s being successful, and wonder what they can do to be successful. Maybe if you don’t feel that you have anything inside, you must do that, but composing, like making any art, has to do with the balance between your own inner spirit and the real world. So, if you haven’t cultivated your own inner spirit, there’s very little that you have to offer to the real world. I don’t want to sound mystical about all of this, but I really see this as the one thing Americans must do, because we’re living in an age where there’s really nothing. All of our great artistic institutions are somewhat crumbling, and it’s very, very hard to maintain standards. We have to be that much more vigilant about our own truthfulness inside, and it becomes that much harder and that much more of a challenge for us. I’ve seen it done enough times to know that it’s entirely possible, and the composers that really resonate for me are the ones who have that connection, and can express it properly. Those are the ones that excite me, and it doesn’t matter how they express it. It can be in any style or any possible form, but somehow when there is that connection, it becomes magic and you can see it.

BD: Does the music of Robert Beaser excite you?

RB: Ah, yes! [Both laugh] It better, because if it doesn’t, I don’t let it out. I work very, very hard in my own studio. People who know me will corroborate this. I’m very hard on myself because at the end of the piece I want to really feel like there’s something there, and that I’ve done something which is going to illuminate something somewhere. It’s a really hard judgment call, and sometimes you’re very close to it and you don’t know. I have a lot of self-doubt every time I go to the piano. I don’t know any artist who I respected that doesn’t have great self-doubt. The artists who feel that they can take the world by storm generally write the most empty music.

BD: [Optimistically] But you must have enough self-confidence to know that eventually it’s going to be right.

BD: [Optimistically] But you must have enough self-confidence to know that eventually it’s going to be right.

RB: Each time I start a new piece, I look back at the pieces I’ve written and wonder how I did that. I really haven’t a clue, and there is a period of fear. There was a period of fear starting this piece

— like I couldn’t do it — and you have to overcome that. It’s like climbing a mountain. You have to overcome the fear, and once you do it, it’s exhilarating. But I will ready admit to having that fear each time I start, because you have to be humbled in front of the music that’s been written in the past. It’s a very humbling experience to see what’s out there.

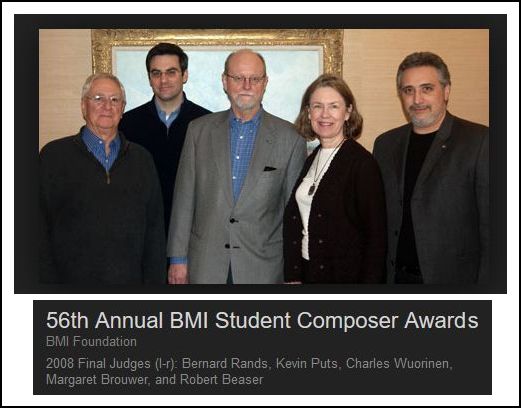

BD: Do you feel you’re part of a lineage? [_Vis-à-vis the photo at right, see my interviews withBernard Rands, and Charles Wuorinen._]

RB: I would like to. I feel very connected to that, and I love feeling connected to that. One of the things we missed in the post-War period was feeling connected. We were so busy trying to negate it, that weren’t able to feel connected. So, composers of my generation are trying desperately to feel again that they’re part of some sort of continuity, because without being part of a continuity, we cannot build on the past, and we have to build on the past. It’s all we have. When I’m asked to write a piano piece, or a piano concerto, for example, or a string quartet, you look at the literature and say,

“My God!”But that doesn’t mean that you don’t try. It just means that you’re humbled by it. It doesn’t mean that you say you can’t do it. You’re first humbled by it, but you can do something here. You know in your heart that this is something you can make your own. Some people just say they’re going to write a string quartet, no problem, and they’ll write it in a few months.

BD: They crank it out?

RB: They crank it out. Some of it, by the way, is incredibly facile, and some of it is rather successful, and people can like it. But for me, more often than not, that signifies that the person doesn’t have an understanding of how they connect to the literature, and that’s really important. It doesn’t mean that you have to write old-fashioned music. You can write very, very way-out music, but some of the best way-out music still has a connection to the past in many ways. There’s always a thread, and you feel the threads.

BD: Have you basically been pleased with the recordings that have been made of your music so far?

RB: Recordings are problematic because they’re not live performances, and a live performance is always, in some way, preferable. But then a live performance contains mistakes, so you have to weigh that in balance.

BD: One last question. Is composing fun?

RB: Yes, it’s great fun

—sometimes! Other times it’s really excruciating. I would say on balance it’s more excruciating than fun, but when it’s fun, there’s nothing else like it. So it’s a bit, I guess, like being addicted. I’m not addicted to anything, so I don’t know, but I guess I’m addicted to composing because I’m addicted to the way I feel when I’m composing at those moments.

BD: Is it worth it in the end?

RB: Oh, sure. There’s really nothing else like writing a piece of music and hearing it performed, and listening to it, and understanding that it’s being played for an audience, and hearing the audience react to it. It’s an extraordinary experience, and I wish more people could have it. I’m very privileged to be able to have that sort of experience, and I’m extremely privileged to be able to have it here in Chicago with the Symphony. But I’m privileged every time someone plays my music, and lavishes it the attention and real wisdom on to it, and make something out of it. I’m constantly touched.

BD: We hope for lots more pieces from your pen.

RB: Thank you.

© 1991 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 18, 1991. Portions were broadcast on WNIB two months later, and again in 1994 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was withWNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.